Britain no longer has a sergeant painter. The role petered out in 1782. And yet in his cheery new exhibition at the Royal Academy in London, David Hockney seems to have given himself the task without anyone asking him to perform it.

The sergeant painter’s job was to be the national supplier of art: the pictorial equivalent of the poet laureate. Working for the monarch, they painted portraits, marked occasions, decorated the moment. Van Dyck did it for Charles I. Hogarth was briefly SP for George II. Right now, as the second Elizabethan era rages against the dying of the light, we clearly need some national cheering. So up steps Hockney.

His RA show could hardly be more uplifting. It has as its main subject the most optimistic of the seasons: spring, when nature stirs and the earth rejuvenates. Walking into the posh central galleries at the RA, the brightness hits you like the lights being turned on in a gloomy room. It’s as if someone has found 100 windows to throw open, revealing a crisp and light-filled spring beyond.

It’s all deliberate. In 2019 Hockney decided to buy a house in France, in Normandy, specifically to watch the seasons. A few years earlier, in Yorkshire for the first time in decades, he had felt the arrival of spring as something tangible and exciting. In Los Angeles, where he had been living since the 1960s, there is one season: warm. But having been reminded in Yorkshire of the elemental impact of a more varied nature, he set out in Normandy to record it with a daily artwork.

Arriving simultaneously to help him was Covid-19, which imposed isolation, ended travel and stopped distracting visits from friends. The virus created perfect conditions in which to watch nature’s rebirth, an irony that must surely have prompted some trademark Yorkshire guffaws from the pleasantly cantankerous and 83-year-old Hockney.

The initial impressions here are of a textbook spring, recorded with a directness so uncomplicated and innocent it feels like the vision of a child. Lots of trees. Lots of blossom. Tons of zingy green. The occasional glimpse of a gingerbread house. If you saw these images attached with magnets to a fridge you might think they were something brought back from the art class by little Jasper or happy Molly.

It’s an impression magnified by the technique being used: iPad drawing. To make his daily artwork, Hockney has employed a digital app called Brushes, which produces marks that buzz between drawing and painting. It’s a bona fide new technique. And when the results are printed in top-spec digital colours everything has a heightened zinginess to it that took me a while to get used to.

But don’t let the kiddy atmospheres blind you. As you begin to see through the glare of the opening optimism all manner of stimulating and subtle pictorial issues tiptoe into view. The first impression may be bright and innocent, but the impressions that follow grow increasingly complex.

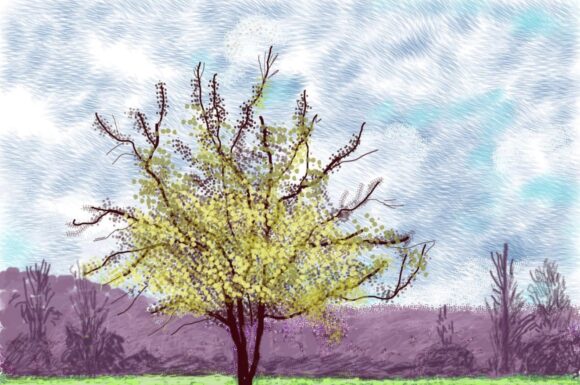

Artistically, the big battle here is to make the iPad marks feel less digital: to slow them down and give them substance. The marks are swift and exact. The first pictures we see, a row of bare trees marking the end of winter and the beginning of spring, are especially direct: single tree, middle of the picture, skeletal branches, grey sky. This winter simplicity spends the rest of the exhibition disappearing.

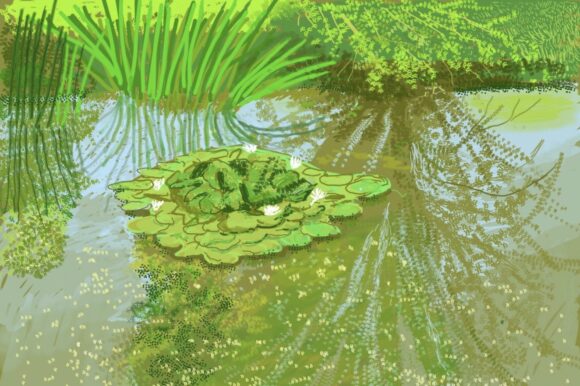

As the spring progresses, Hockney becomes increasingly adept at adding layers and depth to the flat iPad fields, and at suggesting the textures and moods of nature with an increasingly clever interplay of marks. See how convincingly the rain falls on the rippling ponds at the far end of the sequence, how the cherry blossom shifts from firm to soft to nothing as the days pass, how the young corn sways in the fields. Everything grows. It’s the best thing about the show. We’re watching a master conquering a technique.

The nods he gives to other artists also feel increasingly meaningful. Monet, who lived and worked down the road in Giverny, is remembered lightly in the rows of background poplars that loom up near the start of the journey, and more obviously in the twilit ponds that signal its end in Hockney’s most successful brushes with Brushes.

Van Gogh’s emotional responses to the arrival of spring in Arles, and the blossom that announced it, is another insistent nostalgia. The plum trees and cherry trees around Hockney’s Normandy house are treated to a daily examination as their branches fill with delicate pinks and cotton-bud whites. Indeed, the entire display has about it the air of a deliberate turning of the back on the city and a return to the unpolluted atmospheres of the impressionists.

All of which is very au courant, right? In his gingerbread house in Normandy Hockney seems instinctively to have produced a body of work that does the things listed on the tin — celebrates spring, cheers us up, remembers the art of the past — but which says something pertinent as well on the subject of the coronavirus and the new priorities it has prompted. The art may be delicate and lyrical, but the stage whispers emanating from it are demanding a redrawing of our world view and a paying of more heed to the real. Vote Hockney for sergeant painter.

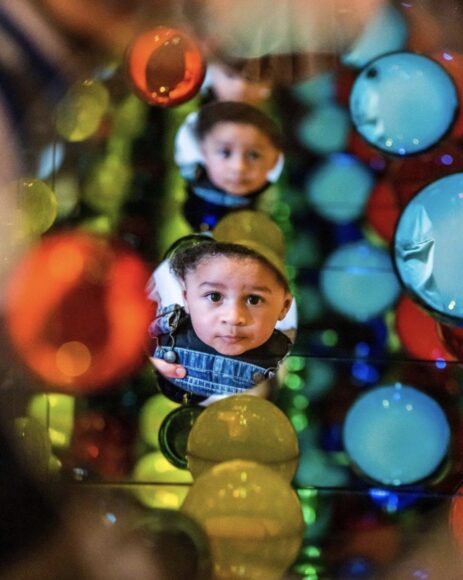

At Tate Modern, Yayoi Kusama, the celebrated Japanese installation artist, takes us back indoors and closes the doors. No more daily exercise for us! Instead we are encouraged to float through a set of artificial darknesses, filled with psychedelic sights, which she calls her Infinity Mirror Rooms.

Constructed in the manner of a ghost train at the fair, which is to say with lots of surprising turns in a confined space, the Infinity Rooms make copious use of mirrors to create the illusion of a cosmic eternity. In whatever direction you look, you see yourself repeated far into the distance.

One room employs elegant chandeliers to strike a Versailles note. Another has twinkling LED lights in the manner of Christmas. It’s briefly fun. But as soon as you leave, you forget it.

David Hockney: The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020, Royal Academy, London W1, until Sept 26; Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirror Rooms, Tate Modern, London SE1, until Jun 12, 2022