Sooner or later art was always going to remember Eileen Agar (1899-1991). Good looks, good demographics, tons of talent, an action-packed life, an address book to kill for: there was never a chance that the present interest in forgotten female artists would fail to locate her.

What a free spirit she was. Her art flutters hither and thither like a butterfly searching for nectar, from style to style, size to size, material to material, mood to mood. Her life, too, was restless, with famous lovers — Paul Éluard, Paul Nash — notable friends — Ezra Pound, Lee Miller — and a travel itinerary that will bring tears to your Covid-weary eyes — from Buenos Aires to Portofino, the south of France to the wilds of Cornwall. Any event that sets out to trace the career of Agar has its work cut out.

Undaunted, the Whitechapel Art Gallery in east London has plunged into battle with a show that tries not only to keep up with her, but also to redefine her. In the past she has invariably been branded an English surrealist. Her noisy inclusion in the famous International Surrealist Exhibition held at the New Burlington Galleries in London in 1936 — alongside Picasso, Duchamp, Ernst, de Chirico — seemed to rubber-stamp the issue.

Yet Agar resisted the label. “One day I was an artist exploring personal combinations of form and content, and the next I was calmly informed I was a Surrealist!” she complained in her autobiography. The label never fitted exactly. Which is why the organisers of this detailed look at her long career have put such evident effort into backing her refusals.

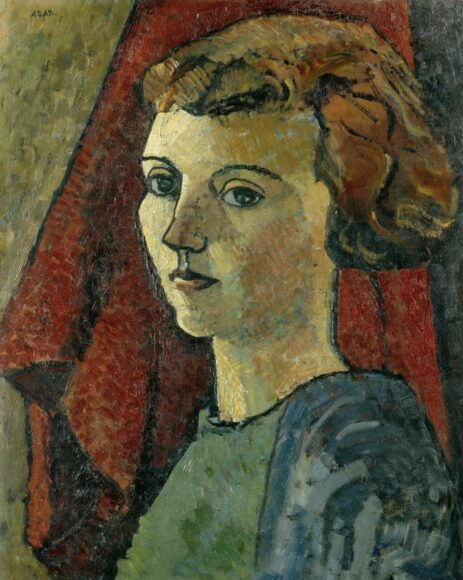

They do it from the off. The painting that welcomes you to the rethink is a self-portrait from 1927. Pretty face. Big eyes. Long neck. It’s lovely, but uncomplicated, painted by a mildly adventurous hand that had perhaps glanced at Matisse and the German expressionists, but which had not sided firmly yet with the moderns. There’s a quiet thoughtfulness to it that was never going to satisfy the carnivores of surrealism.

Agar was born in Buenos Aires to a wealthy Scottish father and a pushy American mother. One of the things she was was a spoilt little rich girl, whose mother ensured she was picked up from the Slade School of Art in a Rolls-Royce. “She came from Greece, she had a thirst for knowledge. She studied sculpture at St Martins College,” and all that.

It’s a background that made her confident and wilful: unafraid of consequences. Having proved her talent with the lovely self-portrait and a clutch of elegant early drawings, the show follows her to Paris and watches as she fast-forwards through all the available influences — Cézanne, Modigliani, Matisse — before arriving at a big choice: cubism or surrealism?

The two trends are summarised on opposite walls of the display. As a cubist, she falls under the spell of Juan Gris and paints gentle monochrome abstractions — symphonies in grey and beige — whose moods are dreamy, as if the cubism were being imagined.

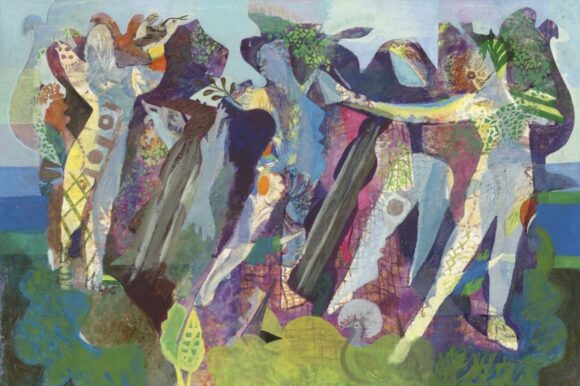

On the other fork, the surrealism is just as uncertain. A couple of looming female heads, in which profiles swap places with faces and eyes occupy cheeks, à la Picasso, are set in gorgeous auras of yellow and red. She has learnt the language, but not the message. Here and there she tries to explore the subconscious, as any surrealist manqué must, but where others go on dark journeys and encounter monsters, Agar hurries through a fairground filled with folk art and coloured signs.

Her most famous work, The Angel of Anarchy, a “surrealist object” made from a bust of her lover, the Hungarian writer Joseph Bard, which has been wrapped in Chinese silks and African beads, studded with diamanté and seashells, is a masterpiece of uncertainty. It’s a man, but feels like a woman. He’s her lover, but she’s blinded him. It smells of voodoo, but also of Kensington. In truth, neither here nor anywhere else on the journey ahead can Agar really be said to settle.

Which is fine by me. It makes for a show that seems never to step into the same river twice. In the 1930s her art stops changing tack from week to week, and starts doing it from work to work. It’s an astonishingly fertile stretch of her career with experiments in collage, frottage, assemblage and every other –age going.

07

07

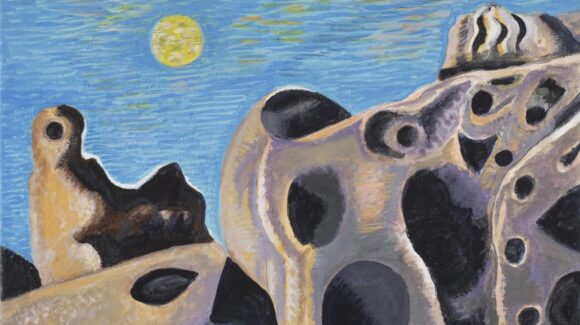

She takes up photography and photographs rocks. She strips for the camera, then doodles over her own nudity. She sticks starfish into paintings, and builds pretend aquariums out of coral, plastic and dried seahorses, thereby inventing Joseph Cornell a decade before he invented himself.

All this happens at a lick in the action-packed downstairs gallery at the Whitechapel. Upstairs is busy too, but the pace slackens. The beachcombing that had given her so many materials and triggered so many connections continues, but spikiness and weirdness are banished, and the mood shifts to lyrical.

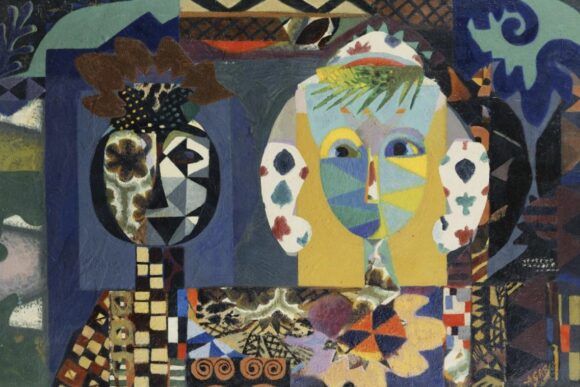

The art grows bigger too. In a curious reverse trajectory she starts working in the synthetic style of cubism that Picasso and Braque began exploring in the 1910s, where the paintings feel like collages. Thus the first half of the journey surges forwards, while the second half winds back. In both directions, the point that Agar was more than a surrealist is firmly made.

Quick addendum: Phantoms of Surrealism, a small display at the Whitechapel devoted to British woman surrealists, includes a perfect scale model of the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition, made by Corella Hughes. It’s wonderful.

Eileen Agar, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London E1, until Aug 29