The other day I posted something positive on X about Yoko Ono. I often do. She’s a strong, independent, courageous woman. I’ve known her for years. There’s a big show of her art coming to Tate Modern. A positive post seemed in order. Or so I thought.

Over the next couple of days my timeline was hit by a shower of bile. “She’s a fraud,” spat one keyboard samurai. The accusation that “she lives off the fame of John Lennon” was busily repeated. A Mr Angry told me “she has perfected the gift of passing off rubbish as art by being surrounded by people who are too pretentious or sycophantic to tell the truth”. I suppose he had me in mind.

Here we were, more than half a century after the Sixties, eighty years after the Second World War, yet still the inquisitionists on X were blaming Yoko for breaking up the Beatles and, I suspect, for torturing their grandfathers in the prison camps of Burma. When it comes to stepping on the toes of Colonel Blimp, few creative ninjas are as experienced as Yoko Ono.

These days, the worlds of art and music are firmly separated. You can’t imagine Taylor Swift loving conceptual art or Stormzy going to art school. But back in the Sixties, they were intertwined. Pretty much every lead guitarist in every Sixties pop band went to art school. Pete Townshend did. Keith Richards did. John Lennon did.

Paul McCartney did not. But when he involved himself with the actress Jane Asher, he stuck a toe into the art world. Asher’s brother, Peter, was partners with Marianne Faithfull’s husband, John Dunbar, in a project in London called the Indica Gallery, named after a plant species of which they were all fond: Cannabis indica. McCartney was one of the gallery’s backers.

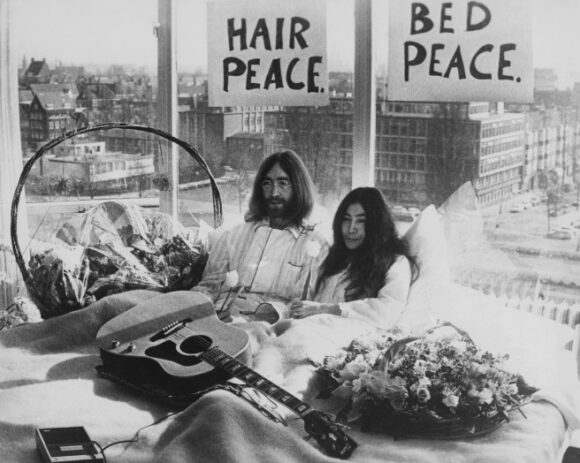

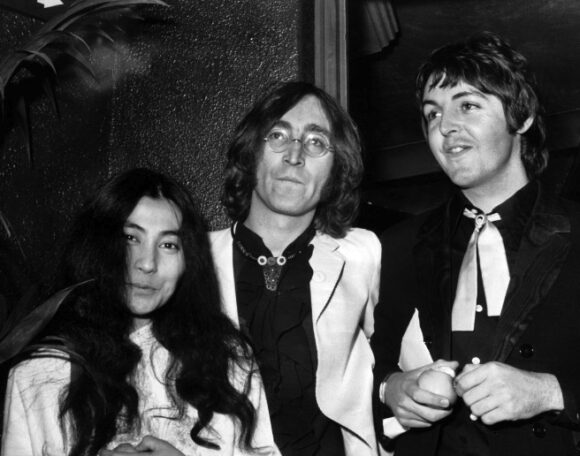

In November 1966 the gallery put on a show by “a Japanese avant-garde artist from America”, which Paul raved about to John. At the preview of Unfinished Paintings and Objects by Yoko Ono, John climbed a ladder as instructed, picked up a magnifying glass at the top and read the word “YES” written minutely on a panel on the roof. It made him smile: a Japanese version of absurdist Scouse wit. Conceptual art had fired the opening arrows of one of the 20th century’s loudest love affairs. You know the rest.

What you may not know, because it’s never made clear enough, is that Yoko was already a big deal in the art world when she met John. In New York she had worked with John Cage and La Monte Young, the leading avant-garde composers of the era. From 1960 her Tribeca loft had been an important venue for some of Manhattan’s most happening happenings. And although she wasn’t an official member of the notorious art grouping Fluxus, she was associated with it intimately, and Fluxus, in the early Sixties, was the Everest of artistic avant-gardism.

A couple of decades later she took me to her Soho studio for an interview and we spoke at length about John and her. When I asked what her favourite Beatles song was, she said Yellow Submarine. Because it was “so surreal”. As we spoke, she insisted that the big “War Is Over” poster behind her was always in shot. Extraordinarily friendly. Totally controlling. That’s Yoko.

I got to know her quite early in my stretch as an art critic. I penned something angry about the art authorities in Liverpool being obstructive about her work. To my amazement, she wrote back telling me to lay off the people of Liverpool because most of them had been great to her. She loved the city. She loved its inhabitants.

I apologised and we kept in touch. When I became head of arts at Channel 4, Michael Grade, the channel’s boss, asked me to think about commissioning some art for its new headquarters in Horseferry Road. Yoko, I thought, would be perfect. Despite her big impact on London’s art life, there was no significant work by her in the city.

Yoko loved the idea and came up with a fabulous plan to erect a giant woman’s leg in the gardens, carved out of white Carrara marble, the same marble Michelangelo had used for his David. Wow, I thought. A giant woman’s leg to kick David’s ass. Yes please. The whole world would come to see it.

Grade was all for it. But at the last minute the management ogres at Channel 4 stamped their foot and said no. It wasn’t the money: Yoko was going to pay for it all. It was the idea of a giant woman’s leg masquerading as art. They thought it silly.

That Christmas Yoko sent me a goody bag filled with all the albums she had produced with John plus a handmade card. Don’t worry, she said. She was used to it. From then on, every Christmas I’d get another goody bag and card. For the new millennium she included a beautiful artwork, a tiny glass bottle with a handwritten message inside: the word “remember”.

Whenever I was in New York I would try to visit her. Once, when I arrived with my daughter, she took us around the apartment she shared with John in the Dakota building and showed me the piano on which they had composed Imagine. My daughter was particularly captivated by the full-size Egyptian mummy in another corner.

In the kitchen a chatty female staff of Yoko loyalists were dealing with her mountain of daily correspondence. Attached to the fridge with magnets was an assortment of Polaroid photos of John. Later she took me for lunch around the corner where we were joined by her daughter, Kyoko, from her previous marriage to the film-maker Anthony Cox. It felt strange to be involved in this rare family meeting. Kyoko looked as surprised as me.

When Yoko was 70 — she turns 91 this month — she sent me a marvellous photo of herself in hot pants looking busty, buoyant, sexy. She was cocking a snook at Father Time, and encouraging everyone, I think, to cock some snooks with her.

I’ve interviewed her on various occasions. When she had a retrospective at the Serpentine Gallery she insisted I do the Q and A. Best of all were the annual trips she organised to Iceland, where she commemorated John’s birthday on October 9 by sending a giant laser beam into the sky from an island in Reykjavik bay.

The first time I went I told her I hoped to see the northern lights. She said she’d organise it. And would you believe, on the ferry back to Reykjavik, there they suddenly were, a shimmering green sky through which Yoko’s laser was communicating delicately with the stars. It felt unreal. Yet it was happening.

The space between hope and reality: that’s Yoko Ono’s territory.

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind is at Tate Modern, London SE1, Feb 15 to Sep 1