Imagine a pebble stuck between two huge rocks. On one side looms the Renaissance, western civilisation’s most prestigious epoch, an era that gave us Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael. On the other side looms the baroque age, the thunderously exciting century that unleashed Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Veláquez, Rubens. Squeezed between these two cultural behemoths was “mannerism”, an artistic moment fated to be overlooked.

The gods of art were having a laugh when they came up with “mannerism”. What an unpleasant name for an art movement. Those who have never heard of it before, and have only the word to go on, will be imagining artifice, difficulty, distortion. The few who recognise it from the story of art will be remembering a fuzzy old master interlude, set roughly in the years 1520-90, that came and went with indecent haste and achieved nothing of consequence. Or so they have been told.

So what actually was it? Well, in the beginning mannerism was the Renaissance going off the rails. The reason we admire the Rinascimento so fervently is because it seemed to represent the conquest of reason over the forces of unreason. By emulating the Greeks and the Romans, the artists of the Renaissance were seeking to banish the superstition and darkness of the Middle Ages.

This might have worked if human beings were as unflawed as Botticelli’s angels. But we’re not. Bubbling devilishly inside us are steaming cauldrons of emotion and passion, fear and hope, love and hate, a taste for horror and every variety of sexuality. It can be capped for a while. But eventually it starts boiling up. And that’s what happened with mannerism.

In fact the pot started boiling while the Renaissance was still happening, most obviously in the art of Michelangelo. The Sistine ceiling is habitually viewed as a Renaissance masterwork, but even a swift perusal of it reveals serious anomalies. Why is everyone up there so sweaty and worried? Why are the angels naked and sexy? In which Renaissance sweet shop did Michelangelo buy those tangy Opal Fruit colours?

It only really makes sense if you understand Michelangelo as a genius bursting with so much pictorial energy and such fierce private emotions that he could no longer play by the rules, as a mannerist waiting to happen.

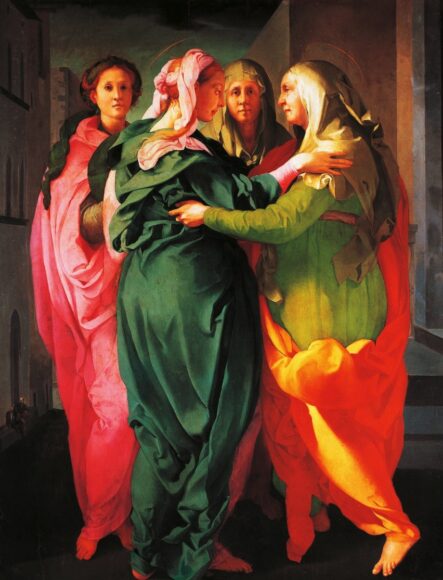

His Florentine followers, Jacopo Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino, continued the prison break. In the modest church of San Michele e San Francesco, in the tiny Tuscan town of Carmignano, there’s a painting by Pontormo that I would drive the Le Mans 24 Hours to see. It shows the Virgin Mary meeting her cousin Elizabeth, attended by a couple of maidservants. That’s it. Yet out of this run-of-the-mill religious moment Pontormo has fashioned a devotional image that grabs you by the hair and yanks you to the altar.

The colours pop as if they have been mixed with sherbet. The figures are stretched to lamppost height. Most tellingly of all, the two maidservants fix us with such penetrating stares they turn their problems into our problem. Five hundred years after the event, Pontormo’s art is still playing mind games with us.

This psychological dimension was something new. Rosso Fiorentino does it too with his tortured Christs, so stretched, beaten and slumped they look like adverts for a charity. When mannerism broke out of prison and went Awol, it threw off the gloves.

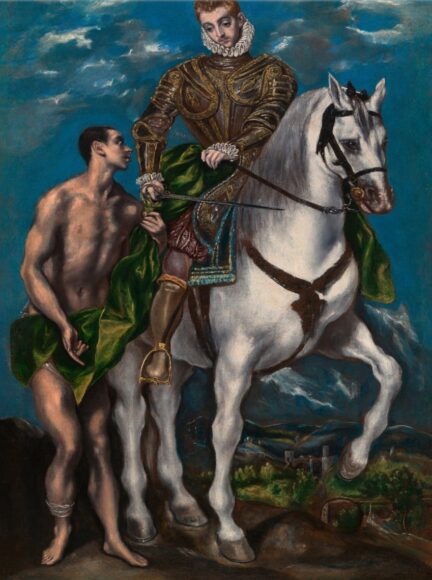

Which is why it was also the first great age of portraiture. A typical Renaissance portrait — the Mona Lisa for instance — can be beautiful and mysterious, but it never jumps the centuries and penetrates your thoughts as actively as mannerist portraiture does. The people painted by Hans Holbein or Giovanni Battista Moroni feel alive and present in ways Renaissance people never can.

Another important mannerist achievement was the unleashing of female artists. A century before Artemisia Gentileschi made her big baroque debut, mannerism was already giving us Properzia de’ Rossi, Lavinia Fontana, Caterina van Hemessen and, most notably Sofonisba Anguissola, who ended up painting more self-portraits than any artist before Rembrandt.

When you start looking inside yourself and disregarding the rules, things quickly get dark and weird. Mannerist art is some of the strangest ever painted. In Mantua, at the Palazzo del Te, Giulio Romano, who had been Raphael’s favourite pupil, let his id off the leash and created a room called the Hall of Giants that seems to be tumbling down onto our heads.

Everywhere you look in mannerist art, people seem to be forgetting their manners rather than remembering them. And this wacky pictorial invention was too thrusting to be contained in Italy. Soon the whole of Europe was at it. When Rome was sacked by the troops of the Holy Roman Emperor in 1527, Rosso Fiorentino fled to France, to Fontainebleau, and took mannerism with him. Soon French art too was growing weird. That famous painting in the Louvre of a naked woman tweaking the nipple of another naked woman is French mannerism at its most erotically complex.

Another Italian who travelled was Giuseppe Arcimboldo, who ended up in Prague working for Rudolf II, an emperor so obsessed with alchemy he had lions and tigers prowling free in his castle. In the crazy court of Rudolf II, creating faces out of basketloads of seafood, as Arcimboldo did, was more of a rule than an exception. Art historians rarely get the chance to bring a fish into a palace. While filming Art’s Wildest Movement, my new television series about mannerism, it was practically compulsory.

Why did this enthusiastic creativity come to an abrupt end? Because, as with all prison breaks, the authorities set about recapturing the escapees. In religious art the notorious Council of Trent, which began sitting in 1545, spelt out a new set of restrictions that artists needed to follow. In the courts of Europe a new generation of absolutist monarchs began demanding portraits that showed off their clothes rather than probed their minds.

Mannerism — excitable, interstitial, fleeting — got put back in its cage. But it had done its job. At one of its ends it had broken free of Renaissance politeness. At its other end it had invented most of the effects favoured by the baroque age.

And if we look further ahead still, to the most recent century and our own chaotic times — to surrealism and expressionism; to body art and performance; to the triumph of female artists and the rebellion against European norms — we see mannerism continuing to affect art. It’s like stamping out a fire. The flames may die, but underneath the coals still smoulder.

Art’s Wildest Movement: Mannerism, is on Sky Arts on Tuesday 30 January at 8pm