Word art is one of the more curious ingredients of contemporary art. It’s curious because it shouldn’t exist. We already have an art that deals with words — it’s called literature.

That said, words do have something visually potent going for them. They are, or can be, striking pieces of design. Translating sounds into shapes is a considerable creative achievement. And the cultures around the world that practise calligraphy as a traditional art form — the Islamic world, China, Japan — have achieved exquisite artistic highs.

English, alas, lacks the arabesques and curlicues to make it visually appealing. It’s a blunt and graceless written language, especially in its American variation. A few word artists working in English — Yoko Ono, Tracey Emin — have managed to make something appealing out of their own handwriting. But they are the exceptions.

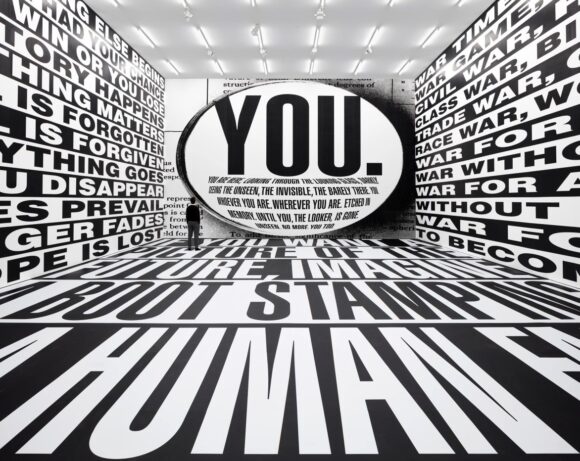

Where English does work, however, where it can have a forceful visual impact, is in the shouty language of the headline or the poster: where the whole point is to get to the point. And among the artists working in this punchy territory, the best and most successful has been Barbara Kruger (born in New Jersey, 1945), whose feisty new collection has opened at the Serpentine Galleries.

Kruger’s trick — and it’s a good one — has been to take the bluntness of tabloid English and use it in ways that are elusive and delicate. She’s like a boxer who punches you in the mouth — but instead of knocking you out, prompts you into poetic leaps and profound ruminations. Simple delivery system. Complex results.

Her heyday was the 1980s, when you couldn’t walk down a street without encountering one of her dramatic exhortations pasted onto a phone box or slapped onto the side of a building.

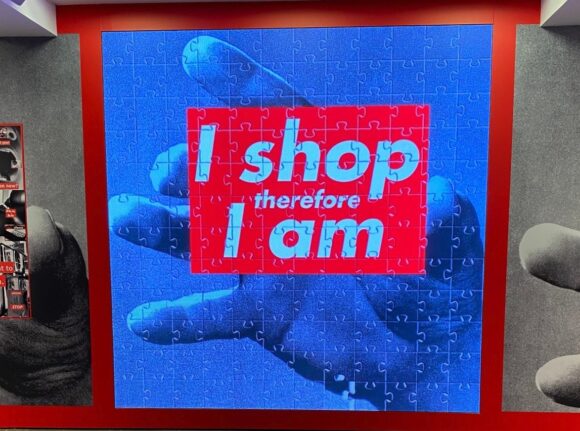

Her most famous visual shout announced “I shop therefore I am”, in big white letters on a red background, written on a name card someone is handing you from the picture. It was a sassy reworking of Descartes’ famous “I think, therefore I am”, aimed, this time, at the collapsed sense of purpose of the capitalist world.

When the abortion debate was raging in America she produced the second of her typographic masterworks, the words “Your body is a battleground”, presented once again in her signature white on red across an image of a woman’s face, half of which was positive and half negative. In this instance it was the pronoun that was fighting the fight. Something that was “yours” had been press-ganged into a societal war.

Both these 1980s pieces are included in the Serpentine show, although both have also been reworked in Kruger’s latest manner. Where most of her generation of notable American artists of the 1980s have struggled to keep up with the times, Kruger has been able to witness the times catching up with her. The more digital our communication becomes, the more directly it heads in her direction.

For her reworking of I shop therefore I am, she gives us a video wall that begins with pieces of a jigsaw puzzle that assemble themselves into the famous slogan, then flicker quickly into a succession of new jingles: “I shop therefore I hoard”; “I need therefore I shop”; “I die therefore I was”. Nothing has a clear meaning. Everything feels meaningful.

And the piece isn’t finished there. Surrounding the video wall is a room-size installation devoted to the various “appropriations” and reworkings of her slogan that Kruger has found on the internet and in the world of advertising. Constantly repeated on Instagram, constantly copied on posters, constantly adapted by the keyboard comedians of the internet, her signature exclamations in Futura Bold have spawned a huge digital industry of quotes and forgeries. Where her original piece was a lament on capitalism, her reworking of it has become a celebration of the digital world’s boundless desire to be seen and heard.

Kruger’s Serpentine expansion into the metaverse — her move off the page and into the ether — is generally successful. The dynamics of the video wall suit her. In a sarky and cutting reworking of the American pledge of allegiance, she turns “I pledge allegiance” into “I pledge adoration … anxiety … affluenza …” Later in the same pledge, “to the flag of the United States of America” becomes “to the flag of Divided Sentiments … Deluded Fantasy … Inherited Wealth”. The words skip from accusation to accusation like butterflies flitting between flowers, without ever straying from their overall determination to give modern America a kicking.

All of this works best in the simplest pieces: the ones expanded most directly from her original haiku methods. Where it works less well is in those bigger, longer installations where the haiku turns into a novel. Kruger’s talent for pithy word attacks is not the talent needed for complex video narratives. In the most ambitious work here, a three-screen video lament on Trump’s America that lasts for ten minutes and meanders from text to diagram to photo, there’s too much going on.

Interestingly, and worryingly, the show is due to take a step into central London in March when Kruger is also opening at the Outernet in Soho, the “immersion experience” that has overtaken the British Museum in visitor numbers. The problem with the Outernet is that it’s chewing up electricity. And if you turn off the power there’s nothing there. The old Kruger would have been against it.

Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You. is at the Serpentine Galleries, London W2, until Mar 17