A stimulating way to start the art year is to visit The Cult of Beauty at the Wellcome Collection. It’s an exhibition that prompts the little grey cells into immediate action, sometimes in a good way, sometimes in a bad. At least the damn things are forced to work.

Beauty is, of course, one of art’s great subjects. Philosophers have been philosophising about it ever since Socrates described it as “the most radiant thing to see beyond heaven” in Plato’s Phaedrus. Generation after generation of aesthetic thinkers have tied themselves into blood knots trying to understand beauty. And now I see we are at it too. Sort of.

The Cult of Beauty begins so uncertainly, in so many directions at once, it forced me to go round its commencement twice. Packed with sculptures, images, knick-knacks and texts, the show rattles from topic to topic, angle to angle, like a pebble in a Kenwood mixer.

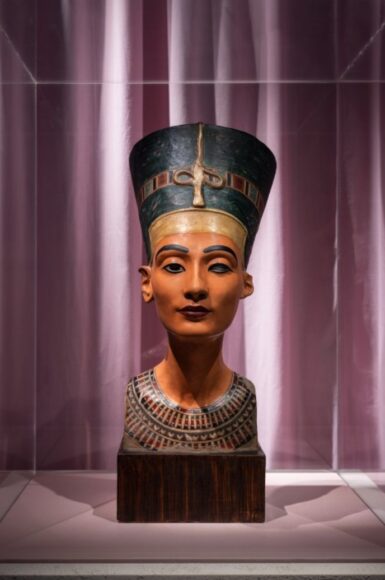

First we have the famously beautiful Krishna being mobbed by adoring gopis, or female cowherds; then we get Nefertiti and the Virgin of Guadalupe, a black Mary worshipped especially fiercely in Mexico; then Elizabeth I has her head eaten by worms in a scary waxwork rumination on the brevity of youth; then the famous Greek statue of a reclining hermaphrodite has its penis removed: Sleeping Hermaphroditus cruelly dehermaphrodited.

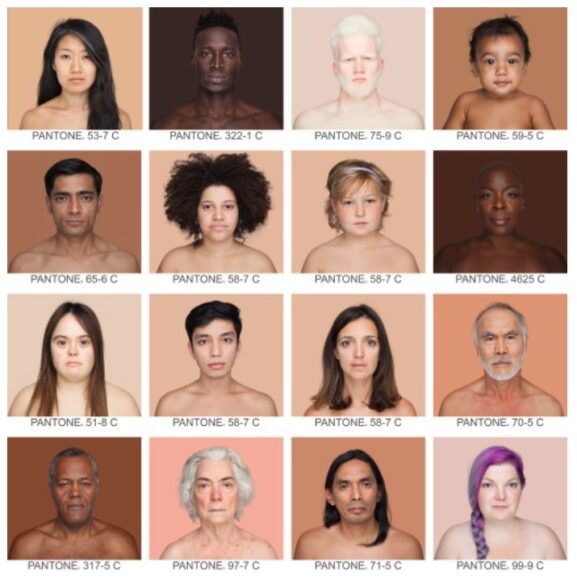

The point being made by this flood of examples is, I think, that beauty takes many forms, that it has many colours, that it flits from gender to gender, and sometimes between genders, in a fashion that the captions repeatedly laud as “non-binary”. At this event “binary” is the bad guy.

Tying all these crazily varied examples together is a quote from the notorious conspiracy theorist and antivaxer Naomi Wolf, who tells us that “ideal beauty is ideal because it does not exist”. It’s true, of course. But choosing the unreliable Wolf for your keynote quote is not the best way to gain the trust of the wandering visitor in a show that we hope is built on secure scholarly foundations. With an investment portfolio of £38 billion, the Wellcome Trust is Britain’s leading scientific charity. If £38 billion can’t buy you the facts, what can?

Alas, the beginnings turn out to be predictive. A show with identity issues is masquerading as a historical investigation of beauty. Fortunately, having failed to point us in a clear direction, the display gets swiftly down to the thing it is best at — bombarding us with absorbing examples. And everything improves.

A cruel vitrine packed with variations on the female corset highlights the distressing anatomical lengths to which women in the 18th century were forced to go to achieve a tucked-in waist. If you encountered the metal devices in a museum of torture they would not look out of place.

Men, meanwhile, making a rare appearance in what is firmly a female event, developed a matching vanity for beards. The hilarious beard vitrine explains how it was rugged soldiers returning from the Crimean War who triggered the Victorian fashion for beards and how, in their case, it led to specially designed teacups into which your beard could droop without getting wet.

Hair, facial or otherwise, is a crucial point of investigation here. A heartwarming film featuring the handiwork of the black hairstylist Cyndia Harvey presents a squad of London girls of African heritage trying the hairstyles their ancestors would have worn. Harvey’s gravity-defying hair sculptures are impressive, but so are the thoughtful comments of the girls as their new hair encourages them to ruminate on their ancient origins.

A large chunk of the show deals specifically with issues of “black beauty”. The familiar figures of the Hottentot Venus, Josephine Baker et al are tugged, once again, into the fray. The examples are often engrossing, but the narrative that binds them together is often chaotic.

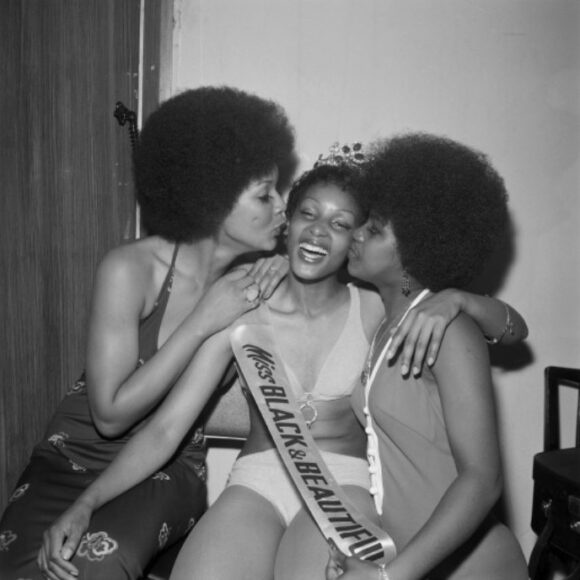

Thus the black beauty pageants of the 1960s and 1970s photographed in London by Raphael Albert — Miss Black & Beautiful, Miss Africa — are celebrated as a space for “Afro-Caribbean self-expression”, while the white beauty contests of the same era — Miss World, Miss Great Britain — are trashed as occasions on which male judges would sit on panels “scoring contestants on their physical appearance”.

In truth, both events shared the same sin. Both were in the business of judging a book by its cover. And if we pop back to Plato for a moment, and his discourse with Socrates, we will hear two ancient Greeks agreeing that beauty is a quality with two halves: an inside and an outside. Not just the cover, but also the book.

The show is probably trying to make the same point. But its ambition to sound fiercely au courant at every stop deflects it from the pathway. Too many contemporary examples are allowed to seize the agenda.

You see it particularly in the section on plastic surgery. The real message here is surely that we have created a society so terrified of growing old that it is hacking itself to pieces to hide the wrinkles. A ghastly photo of Ivo Pitanguy, Brazil’s so-called “pope of plastic surgery”, shows the gnarled old Hippocrates fondling the breasts of a young woman who has come to be improved. She clearly doesn’t need it.

The photo ought to be prompting a discussion about the costs of plastic surgery, and the disfiguring anxiety of a moneyed middle class searching insanely for the fountain of youth. But the captions remain resolutely shtoom on such subjects.

At the end of the day, despite the entertaining distractions, this is a show about people with problems. The Cult of Beauty didn’t set out to prove how many unanchored and unhappy sorts there are in the world today. But that, alas, is what it does.

The Cult of Beauty is at the Wellcome Collection, London NW1, until Apr 28