The power of art, its seriousness, its importance, is easy to forget these days. Too easy. Go round the grim Frieze art fair, as I did this autumn in London, and all you see is hawking, money-grabbing and rich people trying to get richer. Which is why the story of Chaïm Soutine, his painting Eva, and its extraordinary role in the deadly politics of Belarus is so telling. When the modern world seeks, once again, to muffle the power of art, let’s link arms conceptually across the ether, and remember Soutine and Belarus.

He was born there in 1893, in a village called Smilavichy. He was Jewish, the tenth of eleven children. And he was cursed. The curse was that he liked to draw.

Commandment two of the ten handed to Moses by God on Mount Sinai forbids the making of art. “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image,” it insists, “of anything that is in heaven above or on the earth below.” It couldn’t be plainer. Don’t make art. That’s why synagogues have no pictures in them; why Islam followed Judaism in proscribing the use of religious images; and why Christianity has tied itself into knots trying to dodge the issue.

It’s the reason, too, why there are no notable Jewish artists before the 19th century, and why little Chaïm, with his love of drawing, was going against the grain in Smilavichy. One day he was caught in the act by the sons of a village rabbi. To punish him, they beat him badly. His mother was so incensed she demanded compensation, and won the case. With the money, she sent him to art school in Vilnius.

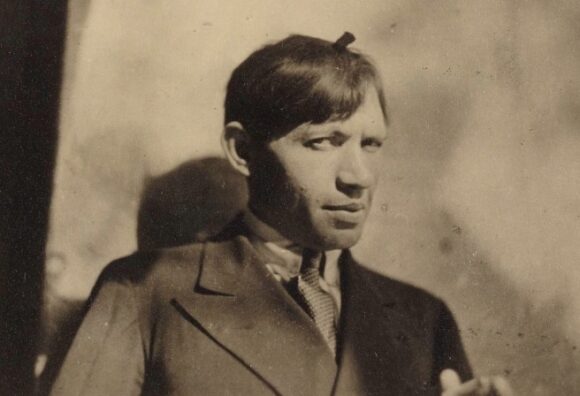

From Vilnius, Soutine made his way to Paris where he fell in with the art crowd and was soon moving in the same circles as Picasso, Braque, Chagall and, especially, his bosom buddy and fellow Jew, Modigliani. The two of them were famous carousers. But where Modigliani’s art seems intent on ignoring his Jewish origins, Soutine’s is unable to get away from them.

Arriving penniless in Paris in 1913, Soutine spent his first years there trying not to starve, while furiously breaking the second commandment. The First World War made things worse. On the evidence of his pictures, food seems always to have meant something loaded to him: something religious, freighted with memories of Passovers and sacrifice.

Right now, in Düsseldorf, a spectacular collection of his work is on show at the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen. The show finishes in 14 days. So it’s arrogant of me to advise you to drop everything to see it, but, if you can, drop everything to see it.

Sixty of his most potent paintings form a twitchy parade of tortured souls and nervous personas. When Soutine painted a face he seemed also to paint the anguish its bearer was going through. It’s this pulsing anguish that gets us to Belarus today and reminds us — because we need to be reminded — of the power of art.

In 2013, at Sotheby’s in New York, the Belarusian banker Viktor Babariko, chairman of Belgazprombank, bought a 1928 Soutine portrait of a woman known as Eva. It’s one of those Soutines that stares straight into you. Dark-haired, in a black dress, her arms folded in a gesture of curiously potent defiance, Eva went for $1.8 million, making her portrait the most expensive picture in Belarusian art.

Babariko had been building up a collection of local artists who had worked in Paris. He had Chagalls, Zadkines, Soutines. In 2020 he decided to stand against the national strongman Alexander Lukashenko in the presidential elections. Before he had a chance to run he was arrested and his art collection was confiscated. Including Eva.

Having been in power for 26 years, Lukashenko was never going to go easily or fairly. The election that followed unfolded tensely amid charges of corruption and vote-rigging. With Babariko in prison, the main challenge came from an unexpected quarter — Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, the wife of a popular political blogger who had also planned to stand against Lukashenko, before he too was arrested.

As a woman, Tikhanovskaya caused Lukashenko little initial concern. Unreconstructed in every dimension, misogynistic, patriarchal, the Belarusian dictator did not consider her a threat. As Lidia Yermoshina, a former member of Lukashenko’s cabinet, advised at the time, Belarusian women should “stay at home and cook borscht”. But that’s not what Tikhanovskaya and other Belarusian heroines did. Instead, they took to the streets and launched what came to be known as an “Evalution”, after the Soutine portrait that became their ubiquitous symbol of protest.

Suddenly, Eva began popping up wherever dissent was needed: on posters, T-shirts, internet memes. One wag doctored her hand so she seemed to be giving Lukashenko the finger. Elsewhere, she bursts out of the picture in revolutionary flames. The Evalution swept the country and at its centre was the worried brunette with the folded hands.

In the end Lukashenko could not be shifted. With election results that belong in a Harry Potter Book of Magic, he claimed victory with 80 per cent of the vote. Tikhanovskaya, who almost certainly beat him, is now in exile in Lithuania. But Eva is still there. Her presence can’t be destroyed. Nor, any longer, can the female contribution to the Belarusian world view. If, in 2024, you want to be reminded of the power of art, give Frieze a miss. Instead, go to Google and type in “Eva, Soutine, Belarus”.

Chaïm Soutine: Against the Current is at Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, until Jan 14