The strangest Christmas I ever spent was in Hiva Oa in the Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia. If you get yourself a world map and a piece of string, and measure out the distance from the isle of Hiva Oa to the coast of Mexico, you will see that it’s about 3,000 miles. That makes the Marquesas Islands in the southern Pacific Ocean one of the most remote inhabited spots on Earth, furthest away from any landmass. It’s what attracted Gauguin to it. And Gauguin was the reason I was there as well.

Gauguin set off for Hiva Oa in 1901. He had already spent several years in Tahiti quarrelling with the French missionaries and battling the forces of “civilisation” that he felt were destroying Polynesia. The best part of 1,000 miles from Tahiti, the Marquesas were so spectacularly distant they had acquired a legendary aura. Cannibals were said to roam the inland forests. A man could live here by lifting his hand and picking the fruit from the trees. Or so Gauguin believed.

It turned out to be another civilisational lie. Hiva Oa was nowhere near as spoilt as Tahiti had been, but the missionaries had still got there before him and it wasn’t what he was hoping for. When he died there aged 54, in 1903, disillusioned, sick, morphined up to his neck, he was no longer able to separate fact from fiction. His last manuscript, recently acquired by the Courtauld Gallery, is a crazy amalgam of opinions, memories and fantasies.

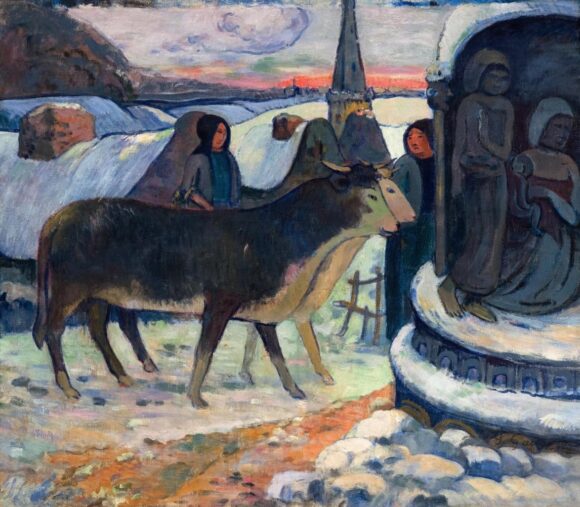

Another of the possessions found in his studio at his death was a picture that he probably started painting in Brittany a decade earlier, but which he finished in Hiva Oa. It’s a winter scene, set in the snow. Two oxen trudge towards a shadowy Christmas shrine in which we can just about make out a Nativity scene.

Mary and Joseph in a stable cradling the baby Jesus. Their shadowy features seem unexpectedly Polynesian. But it’s them, all right.

More about Gauguin’s unlikely Christmas scene in a moment. First I need to continue with my own Yule on Hiva Oa and why it was so forcefully strange. To commemorate the centenary of Gauguin’s death, I’d been commissioned to film a biography, an experience that sent me careering around the world trying to keep up with his voyaging. Gauguin was surely the most travelled artist there has ever been.

As I traipsed hither and thither in his wake, I couldn’t help but notice a direction to his relentless travel. It was always away from somewhere. Some people dream of climbing Everest. Gauguin dreamt of reaching the end of the civilised world.

One of several false narratives about him is that he abandoned his wife and children to go prancing around Tahiti. What actually happened was that his decision to become a full-time artist did not go down well with his Danish wife and her bourgeois family. No longer able to support her and the kids in the manner to which they were accustomed, he was told to leave Copenhagen. Gauguin didn’t abandon his family. The family abandoned him.

On my trip to Hiva Oa, I took my wife and two daughters. We were going to have as different a Christmas as we could manage. On Christmas Eve we visited Gauguin’s grave in a cemetery perched on a hill above Atuona, the “capital” of Hiva Oa. It smelt so beautifully of frangipani.

Buried in the next grave was the Belgian singer Jacques Brel, who had become so obsessed with Gauguin he had followed him to Hiva Oa in his plane “Jojo” and ended up living there, flying the locals to hospital if they got sick. The plane was in the cemetery too, parked next to the two graves.

In the evening we went to midnight Mass and tried to sing French carols, but the chirping of the geckos on the roof drowned us out. When we got back to the hotel we gave each other presents. My wife had forgotten to bring me one, so she gave me a rock she had picked up near Gauguin’s grave.

On Christmas Day we had arranged to go and see the giant tiki of Hiva Oa. Gauguin painted it several times — it’s one of the largest in the South Seas — but he’d never actually seen it. It was on the other side of the island, and by then his sick legs were too weak to get him there. We went by four-wheel drive and had an exotic lunch of ceviche and papaya while some girls from the village raced their horses on the beach. Just as they do in Gauguin’s paintings.

Suddenly, a loud “Yo ho ho”, delivered in an unfamiliar accent, rent the air. Looking up, we saw a dilapidated overland truck shooting along the beach with someone dressed as Santa Claus in the back, riding the truck as if it were a Roman chariot. The truck was full of brightly wrapped presents, which Santa began distributing to the kids who immediately mobbed him.

Sweating profusely in his cotton wool hair and beard, valiantly uncomfortable in his thick red costume, the Polynesian Father Christmas emptied his sack of presents, and drove off to the next village.

Back in the hotel, I opened up my Gauguin book and had another look at that unlikely winter scene with the oxen and the Nativity. As art, it was simultaneously progressive and traditional. Here we were, as far away from home as we could possibly get, yet the mood of Gauguin’s Christmas picture was warming our hearts in a familiar way. As it must have warmed his.