Every art historian worth their salt dreams of discovering an unknown or critically undervalued artist. It’s the big art historical fantasy, and happens only rarely. But it does happen. Until Théophile Thoré-Bürger found him stuffed down the back of the sofa in the 1850s, no one had heard of Vermeer. Art history had lost him. Caravaggio was an obscure presence in art until the 1930s, when the Italian historian Roberto Longhi became his champion and everything changed.

So Laura Llewellyn of the National Gallery and Nathaniel Silver of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston have every right to feel jointly chuffed for unleashing Pesellino on us. “Pese-who?” we mumbled in unison when their unveiling was announced. Pesellino: A Renaissance Master Revealed is not just the first show devoted to him, it really does do what it says on the tin.

Born in Florence in about 1422, Pesellino’s real name was Francesco di Stefano. He got his nickname from his grandfather, a respected Florentine artist famed for his banners and coats of arms who taught him and who was called Pesello, after the Italian word for pea. “Pesello” was also Florentine street slang for “a tiny member”, so Pesello was “Little Dick” and his grandson, the diminutive Pesellino, was “Even Smaller Dick”.

Silly nickname or not, he was a prodigy who quickly outgrew his grandfather’s training and began making independent waves on the Florentine art scene.

The Medici duly noticed him. It was they who commissioned the extraordinary painted wedding chest, or cassone, which opens this event like a crack of lightning with a suddenly fierce display of bright, busy, inventive art telling the story of David and Goliath. More of that in a moment.

In Rome the popes also noticed him. For Pope Nicholas V Pesellino produced a gorgeous illustrated manuscript of the longest surviving poem in Latin literature, Punica by Silius Italicus, about the Second Punic War. The original is in the Hermitage in St Petersburg; it’s represented here by reproductions.

He painted small predella panels for altarpieces by other artists. And when he gained some independence he invented a type of Madonna and Child that was much copied. Finally, at the end of the show, he started an ambitious full-scale altarpiece for a brotherhood of priests in Pistoia, which he was halfway to completing when he died. The plague got him. He was 35.

And that’s it. The life and times of Pesellino (1422-57). Out of these breadcrumbs the National Gallery has created a punchy, vivid, dramatic little event, dominated by the wondrous cassone, accompanied by titbits from the rest of his career.

When you’re confronted with a new artist, the first thing you look for, and hope for, is a distinctive presence: something that unites the examples and makes them characterful. It doesn’t happen here. Not only is the evidence meagre, but Pesellino is not a Vermeer or a Caravaggio — an artist with an immediately loud identity.

One quality that does emerge quickly, however, is the inventiveness of his storytelling. Early on you see it in the weird scene of Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian, the medical martyrs, transplanting the healthy leg of a recently deceased black Christian on to the amputated stump of an unhealthy white Christian. In the modern world it would be recognised as an act of racist limb farming. In Pesellino’s Florence it was religiously uncontroversial. Indeed, the way he paints the scene seems remarkably matter-of-fact.

The leg story comes from a predella made for an altar by Fra Filippo Lippi, the Renaissance master with whom Pesellino is easily confused. The stretch of art history he shares with Lippi, Andrea del Castagno and Benozzo Gozzoli was often a shared achievement, a joint enterprise. Thus, somewhat perversely, his taste for collaboration can be listed as another of his defining characteristics.

When he became an independent master, the style of Madonna and Child that he invented clearly filled a gap because there are so many versions of it (noted in the catalogue but not included in the show itself — a missed trick, I think). And that final altarpiece of his, the one left half-finished at his death and completed by Lippi, is so smooth a display of collaborative skills it’s hard to discern his specific hand in it.

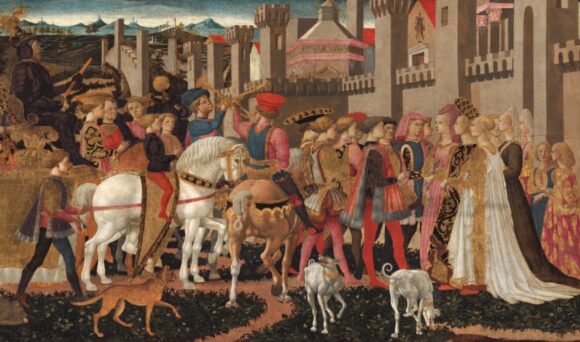

So we’re left with the cassone. And boy, what a cassone it is. Perhaps the finest Renaissance cassone of them all. Painted for Cosimo de’ Medici, the two panels imagine David’s adventures with Goliath. In the left-hand scene we see the young shepherd practising his slinging talents and slaying the giant Philistine. In the right-hand panel the conquering hero returns to Jerusalem in a sumptuous procession with Goliath’s decapitated body slung unceremoniously in the back of a cart.

Recently restored, the glowing panels feel immediately dramatic: a rich painterly feast. The sheer number of figures depicted is remarkable, each one carefully picked out and characterised with obsessive precision. And just look at the way he uses gold highlights to emphasise the ornate costumes or to pick out a play of light.

Pesellino’s skill at depicting animals is quickly evident as well, not only in the many painted horses but in the assorted leopards, lions and bears that accompany the procession.

The storytelling too is twisty and complex. Lean in and witness the young David honing his stone-throwing skills on a jungle of wild beasts. And all this is packed into two pint-size artworks that once made up the sides of a wedding chest.

Big achievement on a tiny scale — Pesellino’s contribution in a nutshell.

Pesellino: A Renaissance Master Revealed, is at the National Gallery, London WC2, until Mar 10