Two big shows by women artists have opened at prestigious London venues. Both are impressive. Both imaginative. Both tinged with what we might call “a tangible national flavour”. For my money, one of the shows is more worthwhile than the other. But which?

At Tate Britain Sarah Lucas, the former enfant terrible of British art, who these days is more of a Bet Lynch of British art, has put together a dynamic and potty tribute to the humble chair. If you love sitting, this is the show for you. Not everything features human stand-ins perched on a range of seating — but most of it does.

Lucas came to prominence at the end of the 1980s as a mouthy Young British Artist. From the start, her art was confrontational and tellingly lowbrow. Most of it seemed to focus on the way men looked at women.

Her most notorious early work, Two Fried Eggs and a Kebab (1992), was a startlingly direct sculptural evocation of the female body achieved with the lowliest of low materials. It’s not in the Tate show, but a selection of her enlarged pages of the grotesquely misogynist tabloid press of the era has made the cut.

Thus we learn, in the Sunday Sport, that the naked and diminutive Sharon Lewis, who was 3ft 2in tall, had become “Britain’s first ever matchbox-sized sex symbol”. In a photo sequence from the Daily Sport readers were encouraged to match the faces of Page 3 “stunners” with close-ups of their breasts. “Fit the faces to the bods and win a cash prize,” blared the headline.

It’s a jolt to be reminded of what was passable in the British press in 1992. There’s a sense here of predatory evil hiding in plain sight. What’s also interesting, though, is the note of humour that survives in Lucas’s observations. She seems to find something reliably funny in the sexism of the great British male, as if the naughty seaside postcards remembered from her youth have played as deep a part in her education as the writings of Andrea Dworkin. The chairs, meanwhile, are everywhere. The show’s first exhibit is a pair of lonely wooden seats called The Old Couple (1992). One has a penis growing out of it, another a pair of dentures clenched sideways to form a pensioner’s vagina dentata.

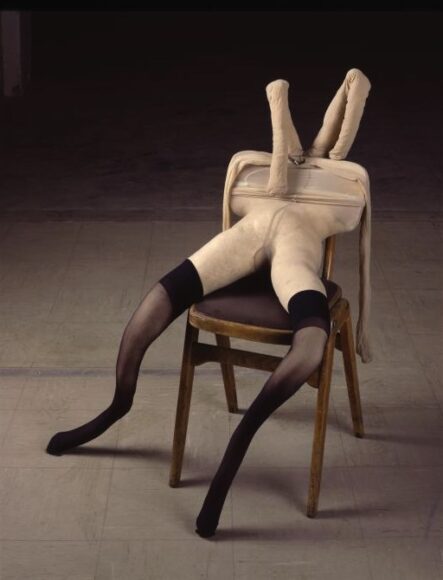

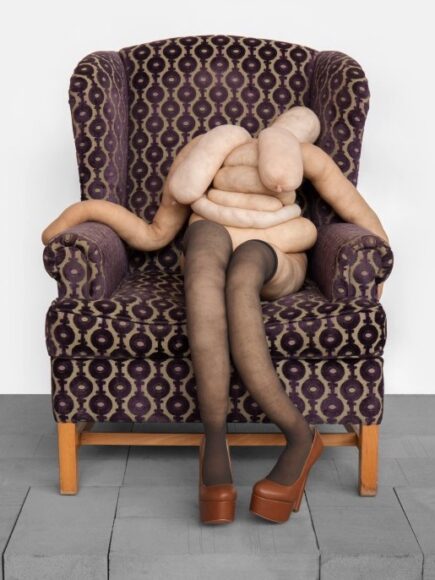

In the event’s most spectacular stretch, dozens of crude female mannequins, assembled mostly from stuffed tights and padded lumps, are contorted into extraordinary poses as they disport themselves on a succession of characterful chairs. Behind them we see big blow-ups of Lucas eating a banana in the Flake manner: suggestively.

The idea here, I intuit, is to rhyme the sculptures with that photo of the naked Christine Keeler wrapped around an Arne Jacobsen chair. At the end of the sequence, however, the mood changes. Fat Doris, a recent work, shows the stuffed tights and blobby boobs drooped sadly into a battered armchair. Having turned 60, “Carry On” Lucas has turned into “Where’s my pension?” Lucas.

In 2015 she represented Britain at the Venice Biennale with a series of works about smoking. It was very British, and didn’t go down too well with the international biennale jet set. The fag sculptures reappear here, where they form part of the exhibition’s closing mood.

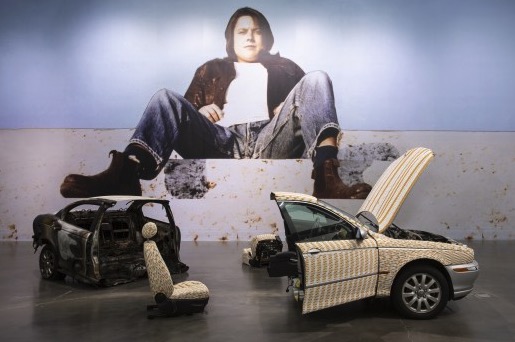

A sequence of blow-ups of Lucas wreathed poetically in cigarette smoke shift us into a dreamy twilight where, you feel, the artist’s own twilight is being considered. A marvellous final sculpture featuring the burnt-out remains of a Jaguar, its roof and bonnet plastered with neat rows of gaspers, finds an elusive rhyme between what happens to your lungs when you smoke and the smouldering corpse of a dead car. It’s a point made the Lucas way — with surprising imaginative leaps, flavoured with drops of 100 per cent proof British pub humour.

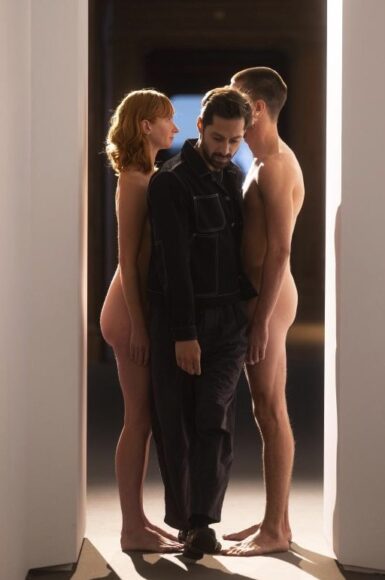

At the Royal Academy, the Serbian superstar Marina Abramovic has been given a rousing retrospective. As the best-known performance artist in the world, she has had to confront the performance artist’s heftiest dilemma more directly than most — how to conserve and present your work when that work is deliberately temporary and transitory.

It’s a problem faced down spectacularly well here by a display that manages to give a real sense of Abramovic’s past achievements while also unfolding excitingly in the now. Dramatic photographs summarise her finest moments. Huge blow-ups blast her face at us. Snippets of film record her fiercest acts. New sculptures transcode her performance ideas into a more tangible form. Not for a moment are you allowed to feel the usual performance lament: I wish I was there.

What emerges from the process, though, is less certain. Serbia’s shadowy historic past — who collaborated with whom in the Second World War?; who succeeded under the Communists? — is dealt with a mite creepily in a series of works culminating in a performance in which Abramovic sits astride a white horse while singing the Yugoslav national anthem.

In her best-known happenings, usually enacted in the nude, she screams, sleeps and gets slapped, burnt and cut with razorblades till her howling visage is burnt into your brain.

Later in the show she goes the full Morticia Addams in a series of works involving the healing power of crystals and meditation stuff she learnt from Tibetan mourners at a funeral.

Thus the event dips readily — too readily — into Wagnerian melodrama. Ever since I learnt that at her 60th birthday party at the Guggenheim Abramovic served up cocktails made from her own tears, I have had trouble taking her performative sturm und drang as seriously as some. Give me Sarah Lucas and her deflationary British pub humour any day.

Sarah Lucas: Happy Gas, at Tate Britain until Jan 14; Marina Abramovic, at the Royal Academy until Jan 1