Iwas talking to a famous art dealer the other day — they’re always good for an alternative view of art realities — and he told me that the biggest growth area in art is the private museum. Everyone everywhere, it seems, is opening them. Especially collectors of contemporary art.

There are many reasons. The tax advantages are huge. And with so much pricey contemporary art swishing about in rich hands, finding a place to put it, and insure it, is increasingly difficult. So people with real money are opening their own museums.

According to the dealer, there were 83 private museums of contemporary art unveiled in the world last year. I haven’t been able to verify that figure. But I can confirm, from personal experience, that there have been a sackful. When it comes to turning nowhere into somewhere, few initiatives are as effective.

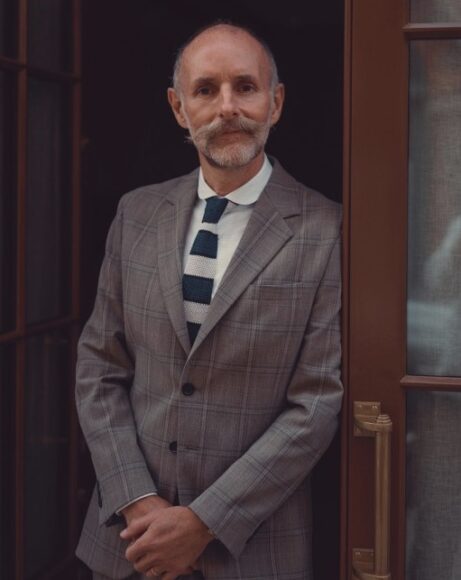

London is already well stocked with them. The Tate began with Henry Tate of sugar fame as its founder. The Courtauld Gallery was started by the cloth king Samuel Courtauld. Then we have the Soane Museum, the Wallace Collection, Kenwood House. All started as private hoards. The most recent is the Brown Collection, the private museum of the remarkable — and remarkably successful — contemporary artist Glenn Brown. It’s in a small mews in Marylebone.

Brown is known for “appropriating” the works of other artists and changing them. What genetic modification does to crops he does to paintings, borrowing an essence from an original, then playing with it: stretching it, reversing it, realigning its symbolism and, above all, repainting it in his trademark shoal of shiny and darting brushstokes. The past goes through him and plops out the other end transformed and deformed. Turned into something exciting. Something contemporary.

This rich relationship with the past, the extraordinary conversations with other artists, is what he has chosen to foreground in his museum. Arranged on five floors, it features a selection of his work mixed up with examples from his collection of old master art. His own paintings sell for more than £2 million. Now we know where he spends the money.

Also thrown into the mix are works by modern artists. So the journey round the Brown Collection is an agile slalom as you slide from old masters to Brown’s work and then on to the work of others. It’s an exciting and informative way to display art. Most importantly, it makes you look. Really look.

The biggest pictures in the museum are Brown’s own. That isn’t just vanity. (Although you can’t blame him. It’s his museum, after all.) Turning the micro into the macro is one of his strategies. Unknown Pleasures, his reworking of a Rembrandt self-portrait — in which he gives Rembrandt a blue face and a Comic Relief nose — is big enough to go on the side of a bus, but the original in the Rijksmuseum is tiny. Like all Brown transformations, it feels as if it is forcing you to look at something you might miss.

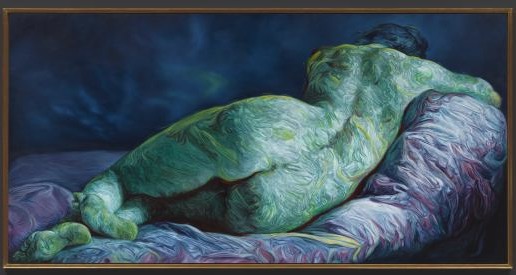

On the Way to the Leisure Centre (which gets my award for the funniest title) is a back view of a reclining nude. It is based on a painting by Pierre Subleyras (1699-1749) that hangs above a fireplace in the Palazzo Barberini in Rome and was long considered to be the most perfect nude painted.

Brown has undone all that. His whopping great beefsteak of a backview is now a Smurf-coloured blue and yellow. Her delicate French bottom has been enlarged into a huge English arse. And I’m pretty sure her head is even smaller.

As well as dazzling inventiveness and brilliant technique, we are getting excellent sarkiness here. Brown’s blue nude is still beautiful, but she’s also weird, unhealthy, poxed with a surreal air. Subleyras’ sublime back view has become the butt (sorry!) of lowly British humour. She’s been plucked out of the foggy heaven of old master land and deposited, heftily, in the here and now. On the way to the leisure centre.

But the experience doesn’t stop there. Next to her in the carefully calibrated hang is a dreamy bit of symbolism by Fantin-Latour (1836-1904) and an Annunciation to the Shepherds by the Dutch mannerist Jan Saenredam (1565-1607). Both old master images feature reclining figures that rhyme and expand the pose of Brown’s blue nude. Thus you find yourself darting from image to image, noting the coincidences and enjoying the comparisons. As I said — it makes you look.

Across the museum this keeps happening. Brown shows his own work and uses it to prompt greater attention to the work of others. It becomes clear that he’s particularly interested in old master drawings. A pair of dazzling sketches of trees by Abraham Bloemaert (1564-1651) have prompted a painting of a tree by Brown that also writhes and wriggles with fabulous mannerist energy.

You look at his tree. You look at Bloemaert’s drawings. You look at the mark-making involved. Backwards and forwards you skip. It’s an involving and marvellously healthy way to look at art. Thank you, Glenn Brown, and your new museum.

The Brown Collection, 1 Bentinck Mews, London W1