The art world is always capable of preposterous behaviour — it’s that kind of world — but even by its own base standards the decision in 2020 to cancel the Philip Guston exhibition that was heading for Tate Modern was cowardly and callow. Cancel culture had sunk to a new low.

At issue were the figures with hoods that Guston had occasionally used in his work. A lifelong supporter of the repressed and unrepresented, famous for his antifascist stance, Guston had included hooded Ku Klux Klan figures in his art since the 1930s as embodiments of social evil. But someone in Tate circles thought the modern world would misunderstand them, so instead of arguing passionately for their relevance they cancelled them. Until now.

The reheated Guston show that has finally managed to get itself seen at Tate Modern has obviously learnt its lesson. From the off it goes out of its way to emphasise Guston’s fight against oppression. By front-loading the event with documentary material explaining the KKK imagery, Tate Modern makes it impossible to misread the art ahead. Anyone who accuses him now of anything other than profound social engagement is, frankly, a dunce. The Tate has redeemed itself.

Guston was born in Montreal in 1913, but brought up in Los Angeles, where his Russian Jewish family relocated in 1917. The anti-black, anti-Jewish rantings of the KKK were an insistent feature of his Los Angeles childhood. In 1923 his father, unable to get work and support his family because of the antisemitic feelings aroused by the Klan, hanged himself in the garage. His son found the body. For Guston the reality of the KKK was deeply personal.

The earliest paintings at the Tate were produced when he was 17. They’re immediately adept. Talent was in his fingers. The figure style is borrowed from Picasso and the metaphysical mood from Giorgio de Chirico — that’s obvious — but it does not stop this first art from creaking with heavyweight symbolism. Here, evidently, was an artist trying to say deep things from the start.

The room filled with his first attempts to find his own style is fascinating but effortful. There’s an awkwardness to the jumbled-up figure scenes in which LA street kids act out the Greek wars with wooden swords and dustbin lids. More convincing are the first attempts at a socially progressive public art, notably an explosive tondo recording the bombing of Guernica, and a rousing mural, painted in Mexico in 1934, in which the forces of evil — in their hoods — are challenged by the forces of righteousness. The actual fresco cannot travel, but an effective film records its heartfelt antifascist roar.

Somewhat perversely, given this lengthy figurative crusade, Guston turned fully into Guston only when he became an abstract artist. In 1934 he moved to New York and fell in with the circles around his LA pal Jackson Pollock. While his figurative art had struggled to find its own identity, his abstractions are immediately different, immediately recognisable, immediately great.

Working with hovering fogs of strong, mural colours, he painted pictures that loom mysteriously, as if you have developed cataracts and are walking towards a shimmering mirage in an empty desert. The central cluster — the shimmering oasis — is the only certainty in these floaty masterpieces.

His method, explained in perfect sets of Tate captions — quelle surprise! — was to start and finish the painting without ever stepping back to appraise it. It led to crowds of central colour, with an unsteady relationship to the picture edge. The results are among the finest of all abstract expressionist paintings, the equal, I would argue, of Rothko and Pollock.

So that’s one huge achievement. But, as he had already proved, Guston was restless. Having scaled the summits of abstraction he began, by the late 1950s, to feel its shortcomings. Political dismay was still gnawing at him. Abstraction could not convey it. By the mid 1960s he was ready to change. The resulting transformation is one of the most notorious in art.

Guston’s return to figurative painting, the remarkable, fearless, crazily inventive, light-touched, sarcastic, slobbish art he began churning out in America’s Nixon years, shocked the art world as it had rarely been shocked. The divide between abstraction and figuration was considered sacred. Abstraction was modern, figuration was not. Painting cartoonish figures in KKK hoods going banally about their banal daily lives, as Guston began to do, wasn’t just an aesthetic betrayal. It was a giant creative sin.

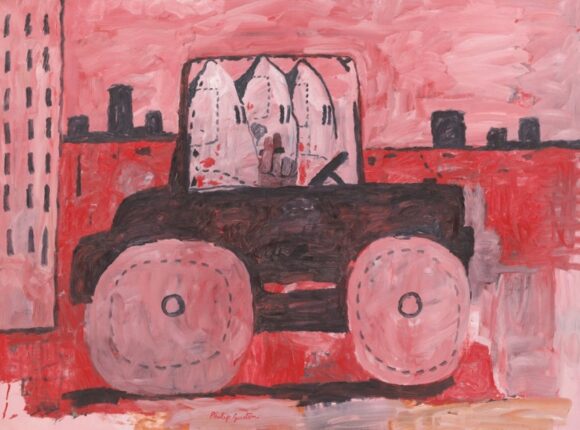

For him it was a return to truth. And it led to a succession of edgy masterpieces that hold everyday America up to brutal judgment. A cartoonish car filled with cartoonish figures in cartoonish KKK hoods drives through a cartoonish modern city. On a cartoon blackboard in a cartoon school someone has cartooned three KKK heads. A cartoonish Klansman before a cartoonish easel paints a cartoonish self-portrait. Evil is banal. It’s everywhere. It’s inside all of us.

Guston never liked to explain himself fully. But his political views, detailed graphically throughout the show, make it inconceivable that anyone should ever mistake these sizzling societal accusations for support of the Ku Klux Klan. Yet this, bizarrely, was the previous worry.

Having stamped on that nonsense, the show moves into its melancholy final phase, in which Guston locked himself away from the world and recorded the insanity of existence with art full of anxiousness and suffering. Outing himself, in a suite of ruthless self-portraits, as a lonely slob, living on cigarettes, booze and the love of his wife, Guston spent his final years fretting sweatily about the demands of survival. In 1980 he died of a heart attack. He was 66.

Do not miss this exhibition. It says so much. And records one of the most important of all American art careers.

Philip Guston is at Tate Modern, London SE1, until Feb 25