In a few weeks’ time, at Sotheby’s in New York, there’s a painting by Joan Mitchell coming up for sale, called Sunflowers. It was painted in 1991 and the estimate is that it will sell for $20 million. Most art world observers, however, are expecting it to go for more. Maybe a lot more.

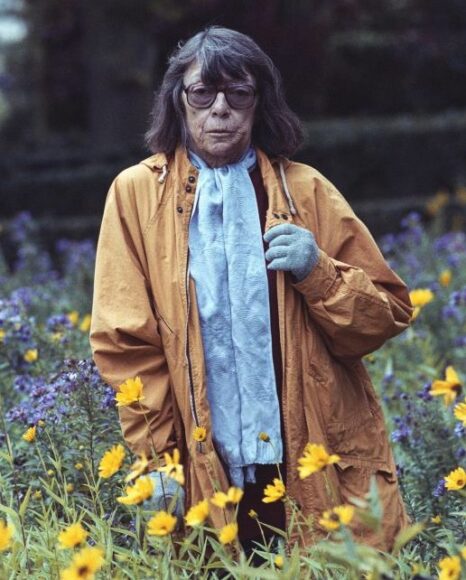

Joan Mitchell (1925-92) is a hot name in art. For decades she was forgotten. I never heard of her when I was studying art history. But art history is a fickle “discipline”, especially sensitive to the vicissitudes of fashion. Things keep changing, and right now Mitchell is desirable. So is her style of painting.

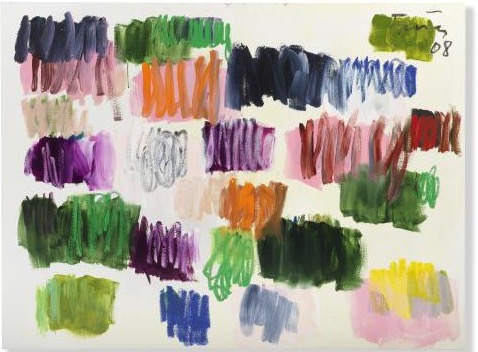

Born in Chicago, she studied art here and there and eventually ended up in New York, where she hooked up with the abstract expressionists. In 1950 she painted her last figurative picture — called Figure and the City. From then on, she was a full-blown, hardcore, determined abstractionist. Blotches and splats were her thing. The poetry of paint was her passion.

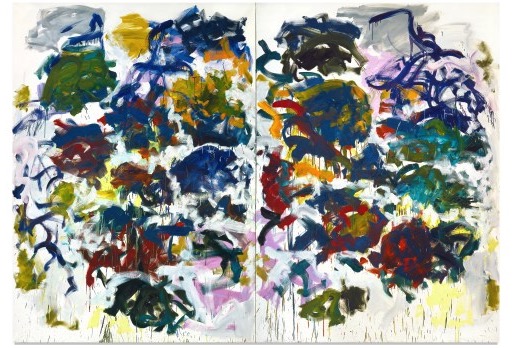

Sunflowers, painted just before she died, is a diptych: a painting in two parts. The left side is busier, with more splodges. The right side is emptier, and a tad calmer. Mitchell had a thing about sunflowers. At the end of the 1950s she moved to France, to be near her heroes, and ended up living in Vétheuil, a town made famous by Monet.

In her garden she grew sunflowers. It was a horticultural tribute to Van Gogh, but also, she explained, because she thought of sunflowers as “little people”. She enjoyed how they stooped when they got older, and the dry and wrinkly form they took when they died. All this she put into her abstractions.

The one coming up at Sotheby’s in November is certainly not a description of sunflowers in full bloom, like Van Gogh’s bouquet. Rather, it’s a visual evocation of lots of late sunflowers in a field, some wilting, most dead, some hanging on to the last moment with touches of green. Like a crowd of people, they come in different shapes and sizes. None of this is specifically described. It’s all magicked up and implied. That’s what you do with abstraction.

As I said, when I studied art history I never encountered Mitchell. She was one of the lost female voices of American art, overlooked in surveys, patronised by the macho New York art world she left behind. The Tate has no significant works by her. She’s almost impossible to see in Britain. It was only when the feminine conquest of art history began to gather speed in the 1990s that she and her fellow female abstractionists were finally noticed. Now she’s in the $20 million class. Maybe more.

It’s not just her gender that’s interesting. So too is her style. The rediscovery of lost female artists has been progressing for decades. It’s welcome — but not new. The same cannot be said of “abstraction”. As art approaches go, nothing has been as flagrantly out of fashion in recent times as the painting of big, flaying, emotional abstractions.

Recognised for decades as the preferred style of the cigar-chomping American jock, abstract expressionism was the art you kept from your neighbours. On the uncool scale, it sent the needle off the gauge. Only whisky-slurping New York art-oafs became abstract expressionists. Right? Wrong. It turns out women did it too. So maybe it was OK after all.

Sotheby’s is not the only auction house that is once again promoting abstraction. Last week Bonhams in London mounted a special exhibition devoted to it. When the auctioneers are interested, it means there’s money in it.

All the dealers I talk to are also telling me abstraction is hot. Indeed, the only ones who appear not to have noticed are, of course, curators, who are always behind the curve on such matters. Eventually they will catch up, and from next year I expect to see lots of abstraction shows in the London calendar.

The curators have not noticed because they learn all their stuff from biennales. The biennales haven’t noticed because they are still obsessed with identity politics, and the inert world of film and video that carries the me/me/me messaging.

One of the things the renewed taste for abstraction is definitely doing is protesting against the waffle and repetition of identity art, with its constant finger-in-the-chest refrain of “listen to me”. People have had enough of being lectured by artists. They want art to do what art is supposed to do: say things to them, with lines, colours and shapes. It’s what art has always done. Abstract painting is its purest form.

I first noticed the tendency during Covid. People began writing in to the Waldy & Bendy podcast I was making with photos of the pictures they and their children were producing. Dumped into conditions that made them come face to face with their own reality, they turned to art. What they produced was urgent, direct, tangibly internal. Not all of it was abstract, but none of it was “realistic”. Instead, they tried to express themselves with shapes, lines and colours. Just like Joan Mitchell, they were exploring the possibilities of their own handmarks.

Another of art’s immutable laws is the law of the pendulum. First art drives one way, then it drives the other way. So that, too, is at work here. We’ve had the cool, wordy, conceptual stuff. Decades and decades of it. It’s time again to uncork the paint pot and splash stuff around. It’s called “the joy of art”.