Jesus walks into a synagogue in Nazareth. He addresses the congregation and they listen with interest. At the end of his speech, he repeats a well-known proverb: “Physician, heal thyself.” The doubting people of Nazareth, he predicts, will be quoting those words at him in the future. The congregation get agitated. And chase him out of the synagogue.

I remembered the story of Jesus and his proverb — told in the Gospel of St Luke — as I tut-tutted my way around Dear Earth at the Hayward Gallery. The show has collected 15 artists “from around the globe” whose work addresses the climate crisis. It does so with videos, projectors, big rambling installations, a towering fake pyramid and assorted sound systems that fill the gallery with the relentless rumble of electronic music. I hate to think how many international crates on how many international flights were needed to create this conflicted event. Perhaps it all arrived by boat.

Among the failings of the modern art world — and there are a lot of them — a thunderous lack of self-awareness is perhaps the most serious. To a shocking degree the art world cannot see in itself what is obvious to everyone else. It’s true in most areas of its activity, but it is particularly true of its dealings with climate change.

In recent years climate issues have become a popular subject on the gallery trail. So popular, they may soon elbow out identity issues as contemporary art’s favourite topic. Yet when it comes to covering the planet with carbon stampings, the art world itself is a huge, avaricious, monstrous Big Foot.

The other day it was announced that Mumbai was hoping to have a biennale. “The city needs consistent art interventions,” its organisers raved. “Please no,” my inner Greta Thunberg whispered. How many biennales can the world survive?

Also announced was the trouble art officials were having in New Jersey with the fourth — yes, fourth — international outpost of the Pompidou Centre: Centre Pompidou x Jersey City. State politicians were apparently questioning the need for it. New Jersey’s art warriors were up in arms. The world really wants a fourth outpost of the Pompidou Centre, they howled. Especially as two more are also being planned in Seoul and Saudi Arabia.

In Saudi Arabia itself, alongside the sixth outpost of the Pompidou Centre, the AlUla heritage region in the northwest was, we learnt, getting two new museums in addition to the five already started. A contemporary museum, designed by the Paris-based Lina Ghotmeh, will be “structured as an archipelago of pavilion galleries interspersed with a mosaic of artist gardens”. Good luck with finding the water for the archipelago. Just recently in the region they had an Andy Warhol show. Presumably because northwestern Saudi Arabia desperately needs an Andy Warhol show for the locals to enjoy.

Art’s ability to turn nowhere into somewhere, and the commercial possibilities of such transformations, has led to crazy amounts of international gallery spreading. Nowhere in the world, it seems, is safe from the most powerful colonising force the planet has ever seen — contemporary art. It’s everywhere. And everywhere it goes, in every new museum, there are crates to be delivered, curators to be flown around, artists to be imported, parties to be thrown and huge amounts of electronics needed to keep the mega-monster flashing, bleeping, growling and cool.

And don’t get me started on art fairs. God knows how many have sprung up around the globe. In London Frieze is opening soon. A significant slab of Regent’s Park will be turned into a money-making tent city, with a huge tonnage of expensive art goodies imported in expensive crates from faraway galleries. The international rich will fly into town on their private jets to spend enormous amounts of cash not on restoring the rainforest but on buying more gewgaws to put into their vaults.

Despite all that, the Hayward Gallery has the cheek to lecture us on climate change. “The urgency of the situation today — and the frightening scale of the potential calamity ahead of us if we fail to drastically reduce our destructive impact on the environment — makes it tempting to point fingers at a long list of enablers and agents of ecological devastation,” the Hayward’s director, Ralph Rugoff, complains in his introduction to the show, seemingly unaware of the need to point an especially large finger at his own world. “Physician, heal thyself,” I felt like scrawling on one of the posters for Dear Earth scattered about the concrete wastes of the Hayward Gallery.

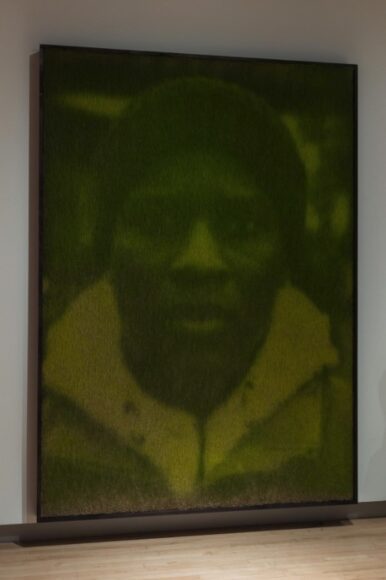

A couple of the artists involved in Dear Earth seem genuinely to get it. Andrea Bowers laments the extinction of assorted birds and flowers in poetic wall pieces that seem genuinely to regret the passing of the species. Ackroyd & Harvey make portraits by shining light through photographic negatives on to fields of grass. Where the light hits, the grass makes chlorophyll and turns dark. There’s a grandeur and something haunting about the resulting images.

At the Serpentine Gallery, meanwhile, the Argentine artist Tomás Saraceno has put up nesting boxes around Kensington Gardens and designed “animal hotels” for the local beasties. How long will they be there? Inside the gallery Saraceno shows us a video he made with the “spider diviners” of western Cameroon. He has also set up a website to advertise their cause.

Going into the show you are asked to hand in your mobile phone. Shame, because I really wanted to send the artist a message. “Tomás,” I would have said, “your heart is in the right place, but if you really want to help the planet stay at home in Argentina. Don’t fly to Cameroon. Forget the hybrid ducks on the Serpentine lake. Physician, heal thyself.”

Dear Earth at the Hayward Gallery, London SE1, until Sep 3; Tomás Saraceno in Collaboration: Web(s) of Life at the Serpentine Gallery, London W2, until Sep 10