Having read Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race by Reni Eddo-Lodge, I did not expect the Black Venus show at Somerset House to be an uplifting experience. When it comes to guilt in these sensitive matters, I am the full package: white, middle class, middle-aged (going on old) and, to top it all, an art critic. “Wear a crash helmet,” whispered the inner Waldemar to the outer.

But the calamitous collision of opposites I feared never occurred. The show was exactly as billed — a selection of works by black women artists ruminating on the image of the black woman in art. And yes, there are moments of snippiness. But the many levels on which the event develops make it an inquiry rich in depth and intrigue. Above all, it proves how many talented black women artists are at work, how potent they are, and how interesting.

The Venus myth has always been problematic. Ever since the ancient Greeks came up with the notion of a goddess of love, born at sea from the foam of Uranus’s genitals, we have had a particularly complex goddess on our hands. Aphrodite became Venus for the Romans and Venus was an object of desire and an embodiment of fertility. As a persona, she’s problematic because fertility is the sine qua non of human survival — unavoidable, critical — while desire is slippery, elusive, shadowy. One half of the Venus myth pulls one way, the other half pulls the other way.

So it’s complicated. If you add blackness to the equation you have a fiery stew of big issues and fuzzy directions. To its credit, Black Venus accepts this complexity. Not for a moment does the show settle into an obvious path. Its final position is more guessing game than solution. Which makes it a riveting event.

A short documentary section reminds us of the grim events that prompted these ruminations: the story of the Hottentot Venus. This especially shameful episode in colonial history involved the importation and exploitation of Sarah Baartman, a Khoikhoi woman from southern Africa who was toured around Europe in a freak show. Her steatopygic body, with its prominent buttocks, triggered ugly merriment and confused desire in the regressed European mind. The poor woman was circulated around the Continent’s capitals as the Hottentot Venus on a pay-per-view basis.

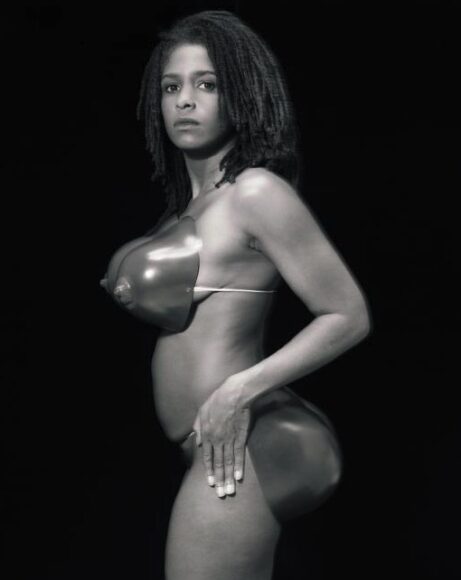

The episode is addressed directly by the American artist Renee Cox, who uses clip-on prosthetics to enlarge herself into Baartman’s dimensions in a nude self-portrait. Staring out at us, firmly, unwaveringly, Cox fires arrows of accusation at every watching white face.

It’s a potent start to the show, not only because it wastes so little time in thrusting us in a post-colonial direction, but also because it hints so tellingly at the tangles ahead. Did this have to be a self-portrait? Do the added prosthetics achieve a similarity or do they emphasise a difference? Does Cox’s evident beauty tighten the argument or open it out?

A big chunk of the exhibition has an accusatory air to it as it imagines how the European mind viewed the African woman. Alberta Whittle rearranges photographic fragments into swirling digital collages that point the finger at the watching white male. C Is for Colonial Fantasy, from 2017, has a suggestive cowrie shell at its centre, with a deliberately pudendal presence, and surrounds it with repeated images of black women in black bikinis with open geodes in their crotches. It’s not a subtle message: the white colonial gaze is only interested in the black female geode.

Another chunk — a particularly successful one — uses costume changes and identity switches to infiltrate the past. Set mostly in the 18th century — where the clash between enlightenment and darkness is at its starkest — these prickly costume dramas achieve the opposite of the Bridgerton effect. Instead of fantasising shrilly about an imagined black presence, they draw our attention tenderly to its absence.

The star here is Maud Sulter, whose noble costume portraits, with their sombre stares, manage to be simultaneously accusatory and celebratory. The accusation is that these black faces would never have been seen in those costumes. The celebration is that they look so credible and poised. Ayana V Jackson, meanwhile, recreates the pose of Ingres’ Valpinçon Bather, using herself as a flesh-and-blood substitute for the fantasy odalisque.

It’s the self-portraiture that pushes this imagery on to complex and whispery terrain. By casting herself as Jeanne Duval, Charles Baudelaire’s mistress — his famous “Vénus noire” — Sulter turns Duval’s fight into her fight, and involves herself in the accusation with special intimacy. The same happens when Coreen Simpson spreads herself nude on a sofa in a typical reclining Venus pose, but covers her face with an African mask. A work that seems to be investigating fantasies of primitivism has also gone out of its way to be about Coreen Simpson.

These are the subtleties that make this such an involving event. When it investigates the past, it investigates the present. When it tackles the perceived beauty of the Black Venus, it also probes the prickly desire of its artists to be her.

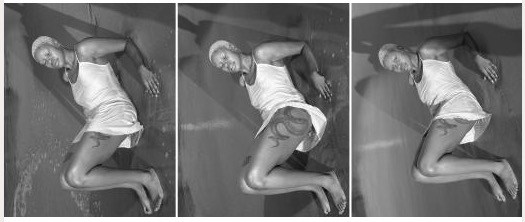

Away from these legible tracks, plenty of the exhibits blur the focus inventively. Carrie Mae Weems’s image of a black woman in a black coat standing outside the British Museum compares blackness with whiteness with the most spidery of touches. The delicate Widline Cadet, starring again in her own art, forces us to look at her in two images where she has her eyes closed, then, in the third, suddenly opens them to study us back. The black-and-white photography adds a poetic note to a deceptively simple face-off.

What a good show. Bravo to the curator, Aindrea Emelife.

Black Venus: Reclaiming Black Women in Visual Culture, at Somerset House, London WC2, until Sep 24