Far back in the annals of art — it was definitely more than 30 years ago because I was still typing on an Olympia — a new movement appeared in Scotland. Its painters were figurative, cocky, colourful, so people began calling them the New Scottish Colourists, or, more hopefully, the New Glasgow Boys.

At the time, art was going through one of its dull phases. German graphs, done with grey, were all the rage. So the full-colour arrival of the New Glasgow Boys had the atmosphere of spring about it. And the artists who made up the group — Stephen Campbell, Adrian Wiszniewski, Ken Currie, Mario Rossi, Peter Howson — were the cocks o’ the north. If only briefly.

I remembered the fireworks of their arrival as I skulked around the tense, sweaty, unhappy, creepy and, eventually, rather brilliant Howson retrospective that has arrived like a dose of cholera in the elegant city of Edinburgh. Not since Mr Hyde went on his gothic rampage has the home of the Scottish Enlightenment had to listen to this much howling from such a monster.

Among the New Glasgow Boys — they had all studied at Glasgow School of Art, or so the myth went — Howson stood out for a couple of reasons. First, he wasn’t actually Scottish, having been born in London in 1958. More importantly, he’d been in the army. And in those days that was a shocker. No one who went to art school had been anywhere near the army.

One of the first paintings I saw by him is now in the window of his Edinburgh retrospective, where it will probably frighten off as many visitors as it attracts. Called The Boxer, painted in 1985, it shows a hulking slab of a man, big muscles, small head, bashing away at a punchbag in the dark. And this isn’t one of your elegant, poetic boxers, floating like a butterfly, stinging like a bee. This is a human cement mixer, whose only direction is forwards and whose only speed is slow. When I first saw it I didn’t recognise it as a self-portrait. Now I do.

Most of Howson’s blundering artistic career has been spent tussling with the beast inside. Once you get your eye in at the sweaty bar-room brawl that constitutes his retrospective, you recognise him, or his spiritual body double, in just about every picture.

In Babylon he’s the chief skinhead in a torn white vest leading the mob’s advance on another mob. In The Third Step he’s the slumped figure in a dark alley crawling towards a distant crucifix on a faraway church. In Wagner he’s the bull-necked baldie taking on all the other bull-necked baldies in a picture that breaks the world record for cramming in bull-necked baldies.

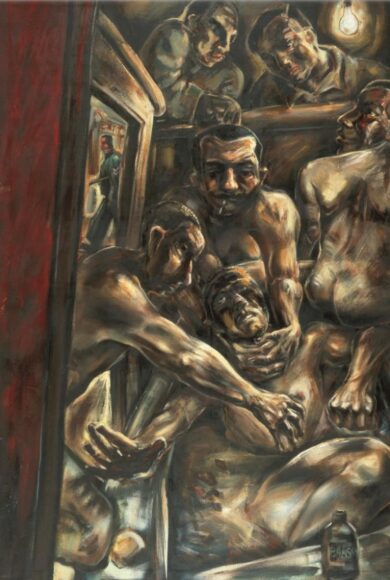

Thickset, sad eyed, ugly as sin, Howson does himself no favours in his own art, and seems, instead, to be drawing attention constantly to his guilt. The earliest pictures here, from the days of the New Glasgow Boys, are already bleak. Regimental Bath shows a bunch of naked squaddies forcing a recognisable Peter under the water in an odious torture scene. Being in the army clearly did something terrible to him.

When he left, he took up bodybuilding and boxing. Now he too could pump up his muscles to Marvel Comics proportions and model his shape on the Thing in the Fantastic Four. Not that it helped. If exhibitions made noises, this Edinburgh retrospective would be keeping Scotland awake at night with its pained bellowing.

In 1993 the army training came in handy at last when he was sent to Bosnia as Britain’s official war artist. Alas, he managed to trigger giggles by coming home early. So much for big muscles and a shaven head. As soon as he was well again, he returned to the fight, and this time filled his notebooks with dark sights and broken details, churning out horrific images of death, murder and rape. They were not things he had actually witnessed. Poor, tortured Howson was once again painting the darkness cast by his own shadow.

When he got back from the Bosnian war this time, he fell apart. The catalogue traces a descent into drink and drugs; a failed marriage, a broken mind. He was saved by rehab and the 12 steps programme. Step 3, the one the skinhead is taking when he crawls towards the church steeple, is giving yourself over to God. Let him do the suffering.

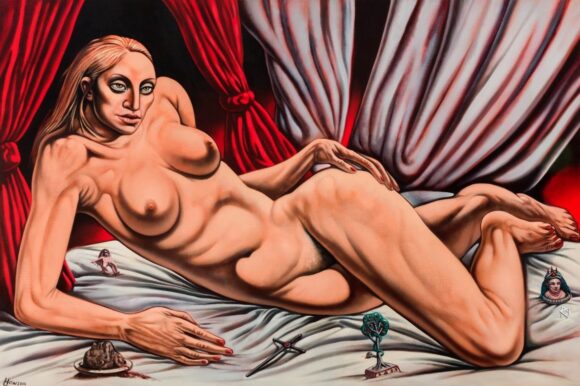

Few subjects in contemporary art are as immediately uncool as Bible stories. Yet the post-Bosnian Howson has been painting little else. In 2002 he stepped out of catechism class long enough to paint a nude portrait of his most famous collector, Madonna, but even that is an image that glistens with something snakish and satanic.

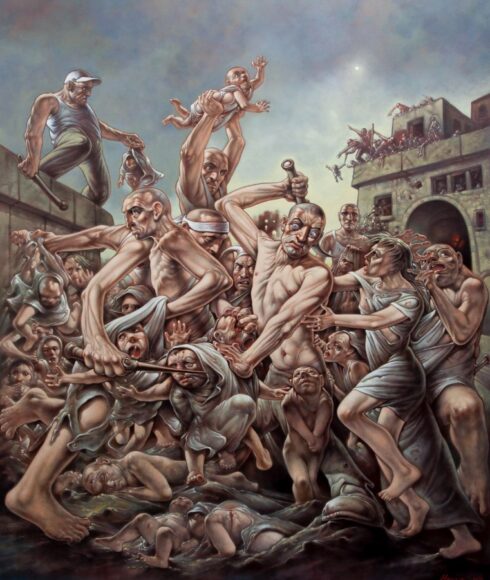

The final stretches of the show are dominated by thunderous religious imaginings. The Massacre of the Innocents is a scene of mass baby murder, swishing in blood and terror. Populo Minuto has the skinhead gang arriving at a forest clearing where they spy a fairytale church glowing in the distance.

It’s all a bit heavy metal. The melodramatic influence of comic books is increasingly tangible. But as the compositions grow larger, and the body count mounts, Howson grows as a painter.

A set of the 14 Stations of the Cross, consisting only of scary close-ups of the abused face of Jesus, is something of a masterpiece. Here we are in the 21st century, yet a British artist is making a telling contribution to one of art’s great traditional subjects.

If you’re delicate, you’ll never be persuaded. The rest of us can only gasp at the enormous quantity of anger, self-pity, terror, rage and, yes, talent that poor Peter Howson puts into his remarkable art.

When the Apple Ripens: Peter Howson at 65, City Art Centre, Edinburgh, until Oct 1