Searching for words to describe the Gwen John exhibition that has arrived at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester, I tried the old Freudian trick of writing down the first words that came to mind. Out popped: sensitive, religious, private. Which will annoy the show’s curator, Alicia Foster. She would rather I had written: thrusting, international, clubbable. That is the Gwen John she wants us to discover in her revisionist show. Alas, art never lies.

Gwendolen Mary John was born in Haverfordwest in 1876. She was never fortunate with men and the first evidence of this was the identity of her younger brother. He was Augustus John, the loud, braying, morally bankrupt braggart whose career completely overshadowed hers and who was briefly considered to be Britain’s most important artist. Augustus was the one they talked about, not Gwen.

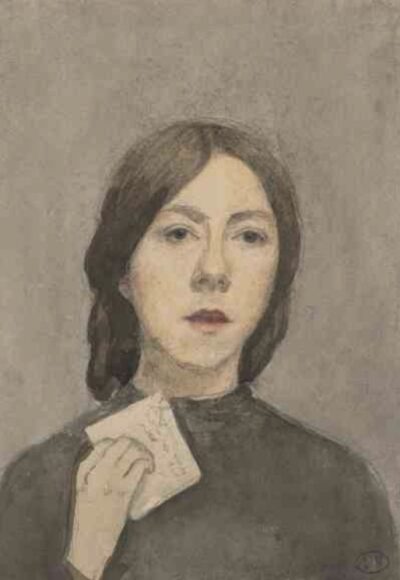

That she was the superior presence — more inventive, braver, infinitely more intuitive — is made clear by a comparison, early in the show, where sister and brother paint the same sitter in the same year: 1903. The sitter is Dorelia McNeill, a friend of Gwen’s from art school who became Augustus’s lover. Gwen paints her in a black dress: hands folded, nervous, with a softly tangible humanity. Augustus paints her as if she were playing Carmen at the Haverfordwest Rep: big dress, phoney fierceness, thunderously symbolic clump of weeds in her hand.

Both Johns studied at the Slade School of Art when it was Britain’s leading art school — the only one that allowed female students. In her determination to present Gwen as less secluded than we usually assume, Foster has enlarged her story with other artists. Thus in the early Slade days we get to meet an intriguing assortment of women who studied with her: Ida Nettleship, Ursula Tyrwhitt, Mary Constance Lloyd. In every instance, I wanted to know more about them and see more of their work. They add up to a parade of lost female talent, and the mood they collectively create is one of betrayed opportunity. Except Gwen.

In 1903 she went on a walking tour of France with McNeill, ended up in Paris, and never came back. So the curator tries her damnedest to place her subject slap in the middle of the exciting, art-crazy milieu that was Paris in the 1900s.

To make the point, we get impressive cameo appearances from James McNeill Whistler, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Paul Cézanne, Rainer Maria Rilke, Edouard Vuillard and Paula Modersohn-Becker. It’s a feast of art. But not for a second does it convincingly challenge the image of John as secluded and dreamy. Her art won’t let it happen! Every picture she paints is steeped in melancholy. Paris may have been spinning around her, but the excitements never quickened her pulse. Until she met Auguste Rodin.

He was in his sixties. She was in her twenties. So it was one of those affairs. At least for him it was. To make ends meet she had taken work as an artist’s model. Nudity was never a problem for her, and the nude John is a recurring presence here in drawings, paintings, photographs.

Rodin seduced her soon after he employed her — they would make love every morning in his studio before his assistants arrived. His mercuric drawings of her sizzle with sexual energy. The old goat even had her form a threesome with another artist/model/lover called Hilda Flodin. You can feel the bodily juices spurting out of him at the sight of their passionate lesbian embrace. Rodin’s erotic drawings are some of his liveliest art.

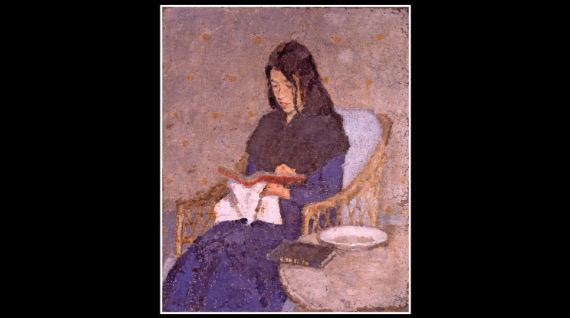

To be near the old goat, she moved to the Parisian suburb of Meudon where he had his studio, and began painting the locals. The results are pensive and spectacularly beautiful. A series called The Convalescent shows a young girl in a blue dress sitting in an armchair reading a letter. Nothing else is happening. You find yourself swapping thoughts with her with the kind of magical intimacy you get in Vermeer. Also like Vermeer, there’s a sense of submerged religious meaning here, as if the young girl in the chair is half of a secular Annunciation.

Rodin dumped her, of course. Went back to his wife. John bombarded him with passionate love letters in the hope it could be mended. It never was. So she turned to religion and in 1913 converted to Catholicism, where, pathetically, she expressed a desire to become “God’s little artist”.

The work she produced in her religious mode bangs the final nails into the curator’s hope that we see John as an artist connected to the thrust and excitement of her times. No amount of wishful thinking can turn the marvellous portraits of nuns she produced as the First World War raged around Paris into anything other than extremely strange, extremely secluded, extremely independent one-offs.

None of which stops this from being a fascinating show — one of my shows of the year. John emerges as a soulful, inventive, brilliant presence. Her portraits are the biggest achievement, but her glowing interiors and spooky night scenes are also compelling.

The one downside is the absence of her best self-portraits. One is in the Tate, the other in the National Portrait Gallery. Shame on the NPG in particular — closed for three years for an absurdly expensive tart-up — for not finding a way to lend to this superior event.

Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris is at the Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, until Oct 8