Saint Francis of Assisi at the National Gallery in London is a happy-clappy affair replete with sugar-coated religiosity and a level of investigative ambition worthy of the under-tens class at a Sunday school. What’s to blame? The coronation moment? Internal confusion at the National about critical standards? Beats me. What I do know is that the show feels more like an episode of Songs of Praise than a serious museum inquiry.

Which is a shame because St Francis was certainly a fascinating artistic presence. Building an exhibition around him is a brave and unusual thing to do. Here was a man who claimed that a wooden crucifix spoke to him and told him to rebuild the Christian faith. Later, a seraphic angel floating in the sky sent stigmatic wounds down to him so he bled, like Jesus, on his hands, chest and feet. He cured lepers. He placated wolves. Even the most cursory reading of his story identifies Francis as a messianic figure with a cultish and edgy presence.

His followers were the first Christian missionaries to arrive in South America, where they spread the faith with evangelical zeal. Indeed, Columbus was a lay Franciscan who believed he was playing a role in the Second Coming and asked to be buried in his Franciscan habit because he assumed he had done his bit for the imminent apocalypse.

Yet none of this dark, crazy, fractious, eschatological history is allowed to inform or disturb the serene progress of the National’s emollient journey. Rather than a Francis whose explosive cult charged Christianity with millenarian ambitions that would usher in the end of the world, we get a Disney saint who is nice to animals and poor people and whose anti-materialistic stance makes him a saint for our times. Try telling that to the Incas, the Aztecs and the Mayans.

The show begins, ludicrously, with a conceptual artwork from 2022 by Richard Long, who went on a walk around the lofty mountain on which Francis’s home town of Assisi is perched and recorded some of the things he saw in a circular text: SPIDERWEB, CROWS, THREE FALCONS. The ambition, as always with Long, is to use words to prompt an imaginary recreation of his journey, but the prompts are so lazy and imprecise they elicit zero picturing of the trek. What kind of falcons? Kestrels? Hobbies? Peregrines? Art is supposed to bring memories to life, not kill them with banality.

In the exhibition ahead, old is mixed with new as assorted detours into contemporary art are combined with old master versions of Francis’s story. Insisting on his continuing relevance is one of the show’s clearest ambitions. Hence Long’s trek last year around Assisi where Francis, the son of a rich cloth merchant, was born in 1181.

By the time of his death in 1226 Francis had given away his riches, chosen a life of poverty, imitated Christ in pointy ways, and gathered a large following of proselytising friars. Two years later he was made a saint: a Catholic speed record. His basilica in Assisi, with its sensational God’s-eye view across Umbria, was also begun in 1228. Two years dead, and already he’s a saint with a basilica. These are remarkable numbers.

A set of 15th-century panels by the Sienese painter Sassetta manage to make something sweet out of Francis’s explosive story. He gives away his clothes, placates the wolf and receives the stigmata in a cheery visual language that might as well be telling us the tale of the Hungry Caterpillar.

The seven Sassetta panels that belong to the National Gallery were once part of an ambitious altarpiece in Sansepolcro that was cut into bits and scattered about the globe. The big central panel, St Francis in Glory, which would have given the scheme the dramatic focus it is missing, now hangs above a chest of drawers at I Tatti, the Florentine villa built by Bernard Berenson, “Mr Five Per Cent”, the early-20th-century art historian who made a fortune in the authentication business. It would have been good to see it at this event. I don’t usually feel a pricking sadness about the cutting up of Renaissance altarpieces — there are too many of them — but I felt it here. Perhaps St Francis was speaking to me.

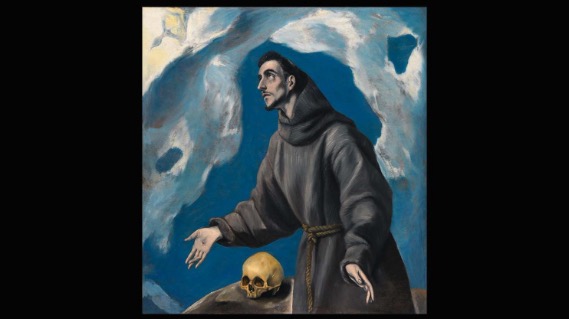

Among the painters charged with visualising him for us, the most successful by far is the Spanish baroque genius Francisco de Zurbarán. His Francis, kneeling penitentially in his coarse Franciscan habit, surrounded by darkness, clutching a skull, gazes up at the heavens through eyes we cannot see because they are lost in deep shadow. It’s an image whose power depends not on the details, but on the absences.

Caravaggio has a go. Murillo has a go. With only moderate success. Among the contemporaries, the best effort comes, unexpectedly, from Antony Gormley, whose lifesize lead figure with outstretched arms, and holes in his feet and hands, manages to evoke the confrontational drama of Francis’s messianic address to the world. Giuseppe Penone, meanwhile, gives us one of his hollowed-out trees that have nothing to do with St Francis.

In the effort to confirm his relevance, the show grows increasingly silly. One section features a 1980 Marvel comic in which Francis, Brother of the Universe — religious superhero! — boom bang bangs his way to sainthood. Another describes the movies made about him. Thus the show ends with Mickey Rourke on a mountain top method-acting his way gorily through the reception of the stigmata. God help us.

St Francis of Assisi is at the National Gallery, London WC2, until Jul 30