I was looking forward to The Offbeat Sari for primitive reasons: I have a problem with holey jeans. Every time I see someone in the street with custom-made tears in their expensive new pants I guffaw. We must be the first society in human history to spend wads of wampum on looking poorer than we are.

The sari, on the other hand, offers sartorial salvation: an antidote. It’s such an elegant piece of attire. A single strip of cloth wound around the body in subtle knots, the sari can arrive at numerous forms with numerous effects: so adaptable, so inventive, so impactful.

On my many trips to India it has provided countless moments of joy. Brightly coloured saris drying on dusty river banks. Exquisite sari patterns flickering in the crowd. If the holey jean is a certain sign of cultural decay, the sari is just as surely a sartorial cure.

So off I went to the Design Museum bursting with expectation. A show devoted to saris has to be a good thing, right? Wrong. The Offbeat Sari is only intermittently a celebration of the sari’s beauty. More often it’s an annoying display of cultural attitudinising by that habitual possessor of poor taste, the fashion industry.

In theory the tale told here ought to be a rousing one. Saris, we learn, are once again trendy in contemporary Indian circles. Viewed previously as old-fashioned clobber worn by grannies, the sari has been rediscovered by India’s bright young things and transformed into attire that is progressive, expressive and rebellious. As I said, that’s the theory.

The reality — as evidenced in a show that confronts us with 90 or so saris from the moneyed ends of Mumbai and Delhi, arranged into à la mode themes — is that a feckless generation of Indian rich kids, seduced by the decadent western fashions blasted at them by social media, has adopted the updated sari as a mark of identity and, in the process, shrivelled its classy historic presence with crass accessorising. No one has yet invented the sari with holes in it. Trust me, it’s on its way.

What we do have is the sari worn with trainers. Not just any trainers but expensive fashion pumps, hand-embroidered with pointless sequins. “Say hello to the Saree Sneakers, the new must-haves for weddings,” go the ads.

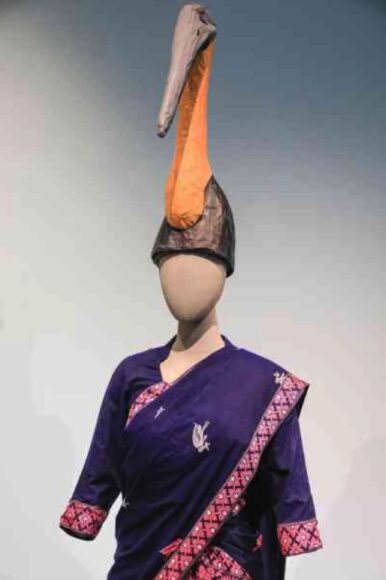

Design agencies with meaningless names — NorBlackNorWhite, Raw Mango — have been busily splattering the indigenous elegance of the sari with Day-Glo dollops of Californian dumbness. Among their inventions is the “pre-formed sari”, a shoulder-revealing, ready-made number that requires no wrapping, so it isn’t actually a sari.

It’s blindingly obvious that all this flippant hitchhiking on the sari’s tradition is a response to the international pounding of Instagram and TikTok. What we’re actually watching is another wave of cultural imperialism where the bad influence of the West is being transmitted to the East via impressionable rich kids.

Thus “Aunty Skates” is the “street” name of a skateboarding granny who took up the sport in her forties and now throws her moves in a special skateboarding flexi-sari featured in “videos that have gone viral”. Prerna Dangi is an Indian mountaineer photographed halfway up a sheer rock face in a blue climbing sari with 15ft of peacock-coloured material fluttering behind her. The sartorial advice promoted by this daft advert isn’t just ridiculous, it’s genuinely dangerous.

One of the themes of The Offbeat Sari is gender fluidity, which, of course, is not a new idea in India. The hijras of Mumbai have a heartening tradition of transexuality that goes back as far as the writing of the Kama Sutra. But the subject is tackled here with a cultural shallowness that feels as if it was learnt at the University of YouTube. Himanshu Verma, a self-proclaimed “Original Gangster Saree Man”, boasts of owning more than 300 saris. Owning 300 saris is not “resisting the status quo”. It’s behaving like Imelda Marcos.

In all this showy phoniness, there are some moments of genuine impact. Raw Mango’s Chikankari Sari, stitched angelically in white, is allowed to remain a gorgeous piece of textile design. So is the China Town Sari, a complex piece of Indian chinoiserie, by Ashdeen Z Lilaowala, that fills its wall generously and fascinatingly. Much of the rest feels like a spread in an in-flight magazine that has been 3D printed.

For a lesson in how to remain genuinely rebellious, everyone involved in The Offbeat Sari should be marched over to the Ai Weiwei exhibition, Making Sense, that has also found its way into the Design Museum.

Masquerading as the first investigation of Weiwei and design, this powerful event is basically a mini retrospective looking at the many inventive ways in which this brilliant naysayer has probed his surroundings. The show is dominated by five “fields” of objects, which the artist has laid out for us in neat rectangles. One contains the spouts of broken teapots; another blue glazed fragments of Chinese pottery; a third is packed with countless bits of discarded Lego.

The usual explanation of these “collection pieces” is that they are commenting on the relationship between the crowd and the individual in communist China. Here they feel as if they accusing the modern world of waste and trashiness. Rising out of the sea of Lego is an intricate wooden pavilion fashioned impressively out of traditional Chinese furniture. No nails. Perfect joins. Something wondrous that has been lost is being compared with a field of imported junk.

The Offbeat Sari is at the Design Museum, London W8, until Sep 17; Ai Weiwei: Making Sense, until Jul 30