There are many artists I would expect to play a leading role — the leading role — in the momentous relaunch of the National Portrait Gallery, but Tracey Emin isn’t one of them. Not in a million years, frankly.

One issue is that she’s not a portrait artist. Not in any previous incarnation of the role. To the best of my knowledge — and I’ve been a keen Emin watcher for three decades — she has never produced a portrait of anyone other than herself. Not unless you count the fleeting glimpses we sometimes had in the past of the male partners she’d taken to her bed. Usually their buttocks.

Another issue is her respectability, or rather the thunderous lack of it. Ever since she turned up drunk on live TV at the Turner prize and told the assembled male cast that she would rather be talking to her mother than to us — yup, I was one of them — Emin has been a garrulous wild child: anti-establishment, anti-rules, anti-false decorum, anti-duplicitous blokes, anti whatever you’ve got that she can be against.

That’s fine if you’re a busy avant-garde artist. But the National Portrait Gallery isn’t any old establishment art location, it’s the establishment art location, charged with keeping a record of the notable faces that have shaped our history — Henry VIII, Shakespeare, Nelson, Victoria — the whole flag. Letting Emin loose like this on the national past is like inviting Johnny Rotten to perform at a Buckingham Palace tea party.

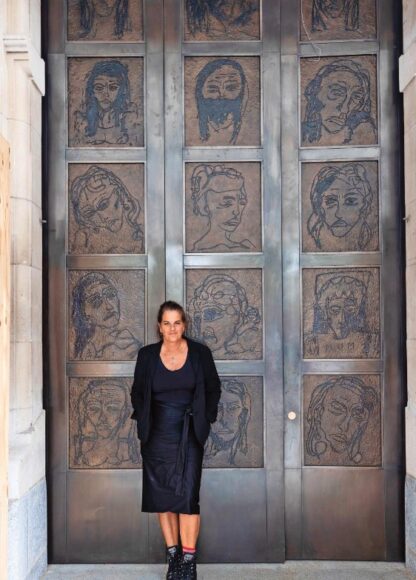

Yet here she is. Invited not only to make a significant contribution to the NPG’s new look but turned, by a crazy modern magic, into the agenda setter: the first sight you see as you mount the stairs of the new entrance. To top it all, no one knew! For two years she has been beavering away on the huge bronze doors through which we will now enter the home of British portraiture — three looming portals, each the height of an average giraffe — yet not a whisper was allowed to emerge about her task. The first I heard of it was the week before I was invited to meet her. Among Emin’s many rich talents we need to add: superb keeper of secrets.

The new doors are dense with faces, 45 portraits in all, arranged in three towering columns — an artistic crowd that feels as if it is covering all the bases: young people, old people, the hairy, the bald, the full-on, the profile. Each face is different but they share a tangible sense of quickness: the unmistakable touch of a single fluent creator.

“It wasn’t a commission. I did it for free,” she blurts, as soon as the handshakes are over. The gallery paid the production fees, but the creation, the idea, are her gift to the nation. In return she had complete freedom to do whatever she wanted and no one interfered.

Freshly installed, still covered in places with the dust of labour, the three towering doors are as tangibly new as a popped-out baby. This isn’t just my first sight of them, it’s practically her first sight as well, of the largest, most prominent, most historically weighty such commission of recent times. As she giggles with typical Emin delight: “They’re going to be here for ever!”

Bronze doors are a Roman invention. Notoriously difficult to manufacture, terrifyingly expensive, symbolically momentous, they are reserved for extra-special entrances.

Only a few have survived the obstacle course of their creation. Rodin worked for 37 years on his Gates of Hell for the Decorative Arts Museum in Paris, but never saw them installed.

Get them right, however, and you carve a deep notch on the bedpost of history. Ghiberti’s magnificent bronze doors for the Baptistery in Florence aren’t just a notable achievement of the Renaissance, they’re a gateway to the whole caboodle.

Emin’s doors feel immediately successful, with all these staring faces greeting you so variously to the museum of staring faces. Only history, though, can give them a final thumbs-up.

And on the day of my visit, the NPG was looking emphatically unready for its future. What a mess: packing cases clogging every vista, pictures covered in paper and polythene, cluttered floors, Sellotaped doorways, strange sucking machines prowling the corridors. I know every big rebuild cuts it fine in the days before an opening, but transforming this chaos into a working museum in the few sunrises that remain before the public unveiling seems an impossible task.

We’ll see. In the meantime, some space is cleared in one of the messy entrance niches for Emin and me, and she resumes the story of her doors.

All the faces are women. On an early visit to the site she was struck by the portraits of famous artists sculpted above the NPG’s main entrance. They were all men. Not only is she righting this historical wrong but the mood she wants to set for visitors today is deliberately more inclusive. A manly museum is getting a womanly makeover.

So, who are all these female faces? Surprise, surprise, they all began as Emin herself. Her own look was always the start, but then, as she let her imagination drift and flow, they turned into other beings and became themselves.

The “Nubian” face with the bald head and earrings is a reference to one of her ancestors. Did I know she was one-eighth Nubian? No, I didn’t. The one with “MUM” written on it feels like her mum but doesn’t look anything like her.

The one with the nurse’s cap? She’s a sort of Florence Nightingale. And yes, there are a few who seem to have escaped from a Mad Max movie. Others look more like Jesus than a woman. But not the ones with breasts.

What she has certainly captured is a rousing mood of variety and inclusiveness. This is not historical portraiture as we know it: a parade of Cromwells, Wellingtons and Churchills. This is every woman and (thank you, Jesus!) every man, a national crowd that instinctively reflects the mix and diversity of modern Britain.

“I think the gallery wants to push the idea of portraiture in a different way. There’s so many different ways to experience somebody’s, let’s say, soul. It doesn’t just have to be what they look like. It could be a portrait of the soul, for example. It could be lots of different things. So I think they wanted it to move away from the idea of classic portraiture. To stretch it.”

Not that achieving it was easy. Each of the 45 bronze portraits was effortfully handmade. The dabs and pits in their backgrounds are the marks of Emin’s fingers searching for a dappled effect. They were done initially as drawings before being transferred with a complex etching process into incisions in the bronze. She did about 80 drawings. These are the ones she picked.

So yes, Tracey Emin is in all of them. And yes, they’re about us. It is a wonderful trick.

The National Portrait Gallery, London WC2, reopens on Thursday