Grayson Perry is being unpredictable. Again. The first thing to note about the big retrospective of his career that has opened at the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh is that it has opened at the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh — and not at Tate Modern or Tate Britain or the Hayward Gallery or the Whitechapel or the Royal Academy or any of the anointed contemporary London art galleries that might usually be expected to host such an event.

The Royal Scottish Academy is a pleasing venue. No one, however, could ever accuse it of centrality or obviousness. By staging his retrospective there, Perry is once again bucking the trend. It’s what he has always done.

Retrospectives are occasions when an artistic career is put on the scales and weighed for value: when we make a stab at assessing its true worth. They are big deals, and they don’t happen easily. Lucky artists get one in their career. Momentous artists, the Francis Bacons, the Bridget Rileys, may perhaps have two. But they are always rare and always portentous.

So the second thing to note about the Grayson Perry retrospective is that it doesn’t feel at all portentous or, indeed, at all rare. Instead, from the start, it hits a festive note. The huge Doric columns that loom above the Scottish Academy’s Athenian entrance have been draped with gaudy Perry artworks. Spelt out in large lettering across the entire front of the building is the artist’s name. All that’s missing are some balloons, and we would have a teenage birthday party on our hands. Or one of those Essex windscreens from the Eighties where Kevin would announce his presence next to Sharon.

From the off, the show signals Perry’s refusal to be intimidated. Others might quake at the prospect of a retrospective, or use the occasion to insist on their weightiness, but not he. What Perry has noticed, and what so many inhabitants of today’s art world always miss, is that you don’t have to be pious to be serious or ponderous to be deep. Oops. I’ve given away the secret of the journey ahead. And we haven’t even ventured inside yet.

Arranged in loose themes, the display commences at a lick, then gets faster, pausing here and there for handy summaries of his development. Having come to prominence as something supremely unlikely — a transvestite potter — Perry has been collecting unlikely accomplishments ever since. No one in British art has had a career anything like his before.

Apart from the art-making, he’s a Bafta-winning television star, a stand-up comedian, a curator and a poet; apart from winning the Turner prize, he has written a column in The Times, delivered the Reith lecture and sung at the Royal Albert Hall.

This same sense of dizzying variety drives his art. Apart from the signature pots, he makes tapestries, sculptures, etchings, woodcuts and has even designed a building: the fairytale fantasy in Wrabness in Essex, which looks like a cross between Hansel and Gretel’s cottage and St Basil’s Cathedral in Red Square. If ever a man seemed hellbent on showing off his range, it’s Grayson Perry in his Scottish retrospective.

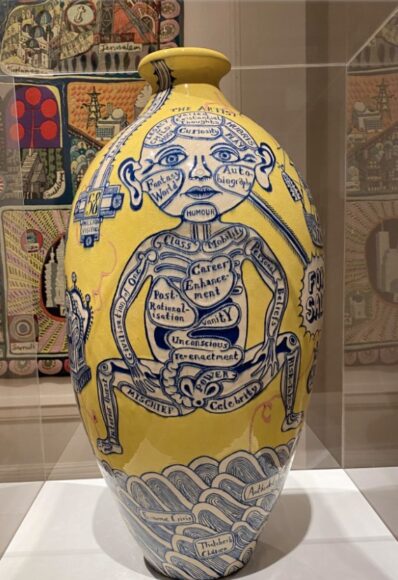

To lure us in, he has selected some of his best works for the opening room: the beautiful yellow pot, called The Rosetta Vase, from his British Museum show; a hilarious mock-heroic sculpture of his teddy bear, Alan Measles, riding a rearing horse across the Alps, like Napoleon; two doomy and fetishistic metal sculptures of pilgrims, a mother and father, weighed down by all that they carry; a weird self-portrait of the artist stretched out on a sofa like a Titian Venus, baring his breasts and a dangling penis. There are times when Perry’s showy transvestism seems clipped on. But then, in awkward flashes like this, it grows suddenly deep and unsettling.

We quickly learn that he took up pottery by accident when a girlfriend’s sister took him to a pottery class. At the time, making pots was deemed profoundly uncool. It’s what attracted him to it. He’s a naysayer by instinct and much of the extraordinary energy on display here is devoted to doing things of which the art world would disapprove.

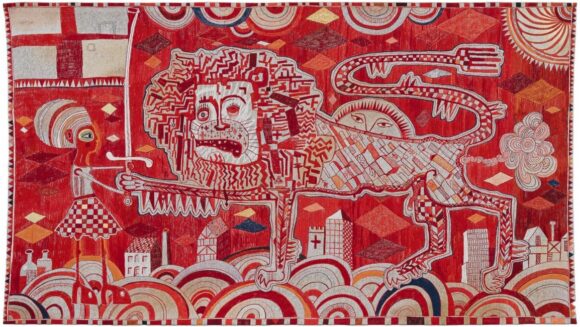

The wall-size tapestries that begin to dominate the show, gaudy bits of full-colour storytelling in which Britain and its failings are picked out and giggled over, have been inspired by the television documentaries he makes, in which his easy interaction with the man and woman in the street is such an appealing feature. But while he’s palling up with the locals, Perry is watching them like a hawk, noting their foibles.

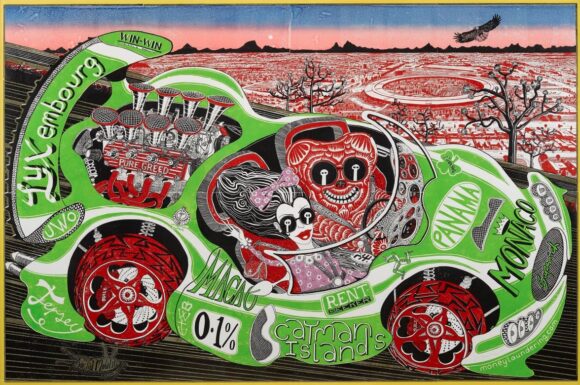

The Vanity of Small Differences is a remake of Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress, in which Tom Rakewell, the 18th-century ne’er-do-well, becomes Tim Rakewell, the 21st-century ne’er-do-well, whose emblematic rise and fall ends in a telling contemporary death when he slams his Ferrari into a lamppost. While being about the rest of us, the multipart tapestries are also about Perry. Among the many things of which he is a contemporary master, we need to count the sneaky infiltration of his biography into most of his output.

Bold and cartoonish, the tapestries are the most obvious examples here of the artist hiding his satirical ambitions beneath jolly surfaces. Lurking under the bouncy imagery is a sarky and scratchy examination of modern Britain. Hogarth has regenerated, Doctor Who-style, and changed his name to Perry. Humour is his sonic screwdriver.

We see less of it in the pots with which he made his name and which, on this impeccable evidence, remain his finest achievements. The reason he took up tapestries and prints, he explains in one of the show’s helpful asides, is because they can reach a wider audience. Pots, meanwhile, disappear into private collections.

Maybe. But there’s a delicacy and intimacy to the pots that lifts them on to a higher artistic plane. Each one is tangibly handmade and personal. They, too, poke about in tricky and complex areas of subject matter, but they do it in a fashion that is poetic and whispery. Unlike the tapestries, they never reach for the megaphone. The best ones glow with a quality I hope to see more of at the next retrospective: beauty.

Grayson Perry: Smash Hits, at the Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, until Nov 12