On February 25, 2022, in the opening days of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Local History Museum in Ivankiv was set ablaze by Putin’s soldiers. The invading Russians were on their way to Kyiv. And although no one can be certain they targeted the museum on purpose, it was the first building in the town, some 40 miles south of Chernobyl, to be destroyed. Attacking culture is a familiar Russian strategy in times of war.

Inside the museum were 25 paintings by Maria Prymachenko. There were other artworks in the burning museum, of course, and precious fragments of regional history — textiles by Hanna Veres, tearful recordings of Chernobyl, rare mementoes of Ivankiv’s Jewish heritage — but it was the potential loss of the 25 Prymachenkos that rang the loudest alarm bells. Had they really gone?

Prymachenko (1908-97) was Ukraine’s best-known artist. Her work had appeared on the nation’s stamps and coins. In Kyiv, she has a street named after her. In space, she has a planet. The Shevchenko prize, Ukraine’s highest national award, was given to her in 1966. Unesco made 2009 “the year of Maria Prymachenko”.

So the Russians knew what they were doing when they bombed Ivankiv’s museum. They were weaponising the destruction of art: dropping an anvil on Ukraine’s national confidence. But they hadn’t calculated properly. They badly underestimated that national confidence. Seeing the building ablaze, a local man ran in and saved as many Prymachenkos as he could carry.

He emerged with ten — some say with 12. By doing so, he turned a story of destruction into an example of salvation. The Russians wanted to break the Ukrainian spirit. They succeeded in doing the opposite.

None of the rescued artworks is in the Maria Prymachenko exhibition that has turned up suddenly at the Saatchi Gallery, like a surprise visit by President Zelensky. The Ivankiv works are stored away somewhere safe. What we have instead is a selection of works from the Prymachenko family collection, a private cache of her art that has never been shown before. Take your sunglasses. It’s very bright and joyful. At least, that’s what you first think.

Prymachenko was what some call a naive artist and others a folk artist. Which basically means she was self-taught. The moment you step into her loudly coloured, loudly patterned, immediately legible parade of fairytale imagery, with its big flowers and its imagined animals, it’s obvious her vision had an umbilical connection with childhood: the kind of connection that is severed the moment you step into an art school.

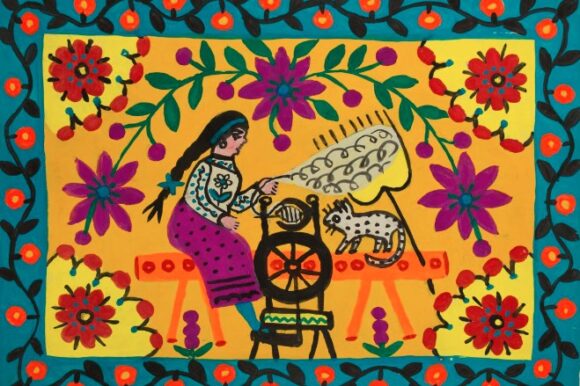

One set of pictures, dating mostly from the 1980s, features charming memories of her village days. She’s the little girl grazing geese by a river. There she is again in bed, frightened (the adjacent text tells us) by an old woman. And look, that’s her too, spinning yarn the old way, on a spinning wheel.

It’s sweet stuff. But deceptively so. Born in the village of Bolotnia, a few miles closer to Chernobyl than Ivankiv, she contracted polio as a child and couldn’t walk without a stick until she was an adult and had two operations. To while away the hours her mother taught her embroidery and how to decorate painted eggs at Easter. That was how it started. Art became her antidote: a release from restrictions. On another continent, at more or less the same time, Frida Kahlo was making a similar journey.

Folk art is what happens to the child’s vision if no one tampers with it. It’s a continuation of the first impulses, the first joys, the first drawings, the first splashes of paint. In the hands of the damaged adult, however, it is nourished by later experiences. The more you look at Prymachenko’s cheery folk art the sadder it begins to feel. The little girl in the bed, frightened by an old woman, isn’t some Ukrainian Little Red Riding Hood, starring lightly in a fairy story. She’s a traumatised adult, remembering the days she couldn’t walk.

These dreamy and personal memories of her little girl years are joined here by the more familiar works in which she imagines bright displays of country flowers or fantasy animals that stare out at us with surprisingly complex expressions. A startled lion-cow. An accusing dog-bear. A snarling cat-sheep in a Chinese hat. This is the kind of Prymachenko art that gets put on stamps and painted on banners. It, too, has a tugging darkness to it that is easy to miss.

Any Prymachenko exhibition is a rare event in Britain. This one is not only rare, it is also uncommonly loaded. War inflates the importance of all art. Prymachenko’s art, by dwelling so nostalgically on a village past, by being so full of picturings of Ukraine as it was — the herded geese, the spinning wheel, the beautiful gardens — stands in for everything the nation has lost. No wonder people run into burning buildings to save it.

At White Conduit Projects, in an extraordinary bounce of the imagination, Jake Tilson has set about evoking the old Tsukiji fish market in Tokyo. I know it. I visited it several times before it was moved. It was a huge, noisy, sprawling, spluttering slab of chaos where, every morning, Japan’s love of fish caused a daily explosion of sights and sounds.

Setting himself a task you would have thought was impossible — a gaijin capturing the mood and look of Tsukiji — Tilson somehow manages to succeed. In a set of models and wall-sized assemblages, packed with calligraphy, painted fish and bits of characterful Japanese detritus, he mimics the wild and exciting presence of the market. Jake Tilson. King of Sashimi!

Maria Prymachenko, at the Saatchi Gallery until Aug 31. Jake Tilson, at White Conduit Projects until Aug 5