Another week, another cock-up. Who needs the Keystone Kops when you’ve got the BBC? Even by Auntie’s declining standards it’s been a bad fortnight. No sooner had the smell of Garygate begun to clear our nostrils than we discovered that the much-loved BBC Singers were to be terminated and that savage cuts to the BBC orchestras were shrinking their personnel by 20 per cent. Auntie, it seems, has regenerated, Doctor Who style, into Wicked Stepmother

Pretty much everybody who’s anybody at the tuneful end of the nation has been expressing their dismay at these amputations. A particularly emotional letter to the Daily Telegraph signed by former winners of Young Musician of the Year, Nicola Benedetti and Natalie Clein, joined by two football teams’ worth of assorted maestros, went tearfully through the many reasons why axing the de facto national choir is such a crazy idea.

In choral rankings, the BBC Singers are at the global top. Their versatility is remarkable. One week they’re at the Albert Hall, the next they’re backing the Pet Shop Boys. And they don’t just sing. In class rooms and workshops across the country they work tirelessly to spread the word about the joys of music. Who belts out our carols at Christmas? – the BBC Singers. Who performed brilliantly at the drop of a hat at Princess Diana’s funeral? – the BBC Singers. So what does the BBC do? It axes them.

Unfortunately, it’s not a surprise. There is something about the arts that pings the bowstrings of suspicion and resentment in the Great British psyche. Especially if the arts in question are in London and someone has spent money on them.

Britain, remember, is a nation that beheaded its own king, the first of our Charleses, for the crime of spending too much money on art. The Puritans simply could not stomach all those glorious Italian masterpieces crossing the channel. Having cut off the king’s head, the roundheads went on to flog off his collection for a pittance, thereby ensuring that the Prado in Madrid now owns some of Titian’s greatest pictures. Our new Charles had better keep quiet about his passion for watercolours. We wouldn’t want to lose a second royal head.

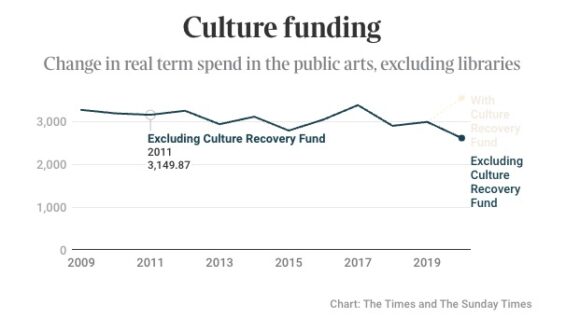

Searching for the reasons for this national mistrust you can take your pick of envy, coldness and puritanism. Perhaps it’s a mix of all three. Last year, the Arts Council announced a series of devastating cuts in the capital amounting to £50 million! The poor old English National Opera was told it was going to be evicted from the Coliseum, where it was born and raised, and shipped somewhere up north like an Amazon parcel out for delivery.

Instead of standing firm and bemoaning such losses, as it was set up to do, our national broadcaster has accelerated the cull. The launch of BBC Four in 2002 was hailed as the advent of a TV channel dedicated exclusively to culture. But that was just spin. What it really was was the beginning of the end. By removing the arts from mainstream television, and isolating them on a satellite station, the BBC was signalling their detachment and making them especially vulnerable to cuts.

And so it proved. The decision in 2022 to move the ‘youth orientated’ BBC Three off the internet and onto terrestrial television ate up whatever cash was left after the latest round of government reductions, and it was goodbye BBC Four as a channel of substance. All that’s left today is an empty husk showing endless repeats of Top of the Pops.

There are only ever two reasons to have a national broadcaster. The first is what we might call the Putinesque reason: to ensure that a subservient state media toes the government line on every issue put before it.

The second reason, what we might call the Reithian reason after the founding father of the BBC, is to cover territories that commercial broadcasters are loath to cover and cater for audiences that are otherwise ignored. That’s why it’s called public service television.

Despite recent signs of trespassing into camp one, the BBC has generally remained in camp two. In the past, wiser heads than the current crop of numbskulls running Auntie realised that chasing after the same ‘Yoof’ demographic as everyone else was a particularly dumb thing to do if you have been set up to be different.

True, the arts loving audience is generally older than the TikTok crowd. But so what? When did growing old become a crime? An audience that takes pleasure in the arts is just as precious, just as worthy of good TV – and in most cases a good deal hungrier for it – than all those happy kids glued to YouTube.

The arse-in-your face obviousness of all this turns acts like the axing of the BBC Singers and the cutting of the orchestras into displays of world class stupidity. By ignoring an audience that loves it and needs it, while chasing an audience that couldn’t give a damn about it, the BBC pleases no one.

Elsewhere in TV land the same mad rush to claim the same young audience that isn’t interested for the same obvious reasons – because it’s too busy surfing the internet – decimated the arts schedules long ago. Remember Melvyn Bragg’s weekly appearances on ITV with his totemic South Bank Show? Remember when Channel 4 was known for its culture rather than its dismemberments?

Back in the 1990s, I myself had skin in the game as Channel 4’s Head of Arts. Our boss, Michael Grade, was super clear about the public service remit and the importance of the arts in the mix. We put the Turner Prize on television. We put Glastonbury on television. We went at weekends from the opera at Glyndebourne to the book festival in Hay-on-Wye.

Exactly like the BBC, Channel 4 is a national broadcaster tasked with the remit of doing what no one else is doing. Its first director, Jeremy Isaacs, was a hardcore arts lover who put these kinds of subjects at the heart of the channel’s output.

But all that has gone. I enjoy Grayson Perry as much as the next frock junkie but he should not be providing the only arts on Channel 4. One of the reasons I felt luke warm about the recent threats to privatise the channel was because I remembered so clearly what used to be there. But isn’t any more.

And if anyone out there genuinely believes that the arts are an indulgence and that the BBC is right to sling the BBC Singers in the trough, they should have come with me to Ukraine last year to witness the heroic effort being made to hide and protect Ukrainian art from Russian missiles. In times of war and grief, the importance of the arts as a national resource become fiercely evident.

Someone should write a song about it for the BBC Singers.