There’s a hairy wart on her cheek. Her nostrils flare like a chimpanzee’s and there’s something simian, too, about the distance between her nose and her mouth. Her forehead is crudely domed. Her ears stick out. However charitably we may try to observe her, it cannot be denied that the Ugly Duchess is unlovely. The question is: why?

Painted in around 1513 in Antwerp, Quentin Massys’ portrait of an old woman has been a showstopper since at least 1869, when John Tenniel used her as the model for the Duchess in his illustrations for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Today she’s one of the most popular paintings in the National Gallery (people do love that postcard), and it’s well nigh impossible to walk past her without stopping for a happy giggle. Ugliness of this profundity is rarely encountered, even in art. What, then, was Massys up to in his most celebrated picture?

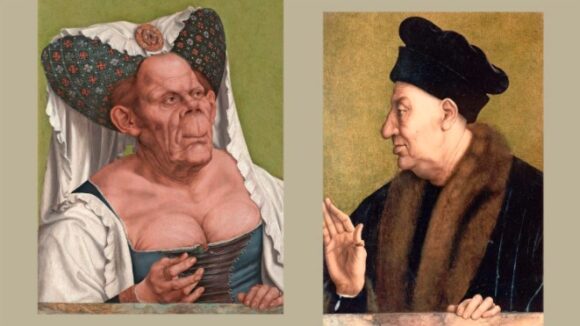

The Ugly Duchess: Beauty & Satire in the Renaissance tries to reveal all. The thoroughly engrossing investigation slaps us awake by surprisingly announcing that the duchess is part of a pair. She has a partner! And there he is! The catalogue duly lumps them together as the Grotesque Couple.

At some point in the 18th century the two ends of this extraordinary pairing were separated. He was lost in the art market. She blundered through various owners before ending up at the National in 1947. So their sparky reunion has had to wait.

He is neither as ugly as her nor as obviously caricatured. Indeed, he’s something of an everyday Joe. Were it not for the parapet running beneath the two of them, crossing pointedly from picture to picture, and the dendrological evidence of the wooden panels they share, you would not immediately suspect them of being a deliberate couple.

She’s turned towards us; he’s in profile. She’s ornate; he’s dressed simply. Follow their eye lines, though, and it’s quickly clear that the two pictures are interacting across the divide. She’s twiddling a tiny rosebud pointed at her sagging bosom; he’s saying: “Hi.” So it’s some sort of intercourse. But what kind? More on that in a moment.

First, the show needs to be praised loudly for its other exhibits, and especially for dragging Leonardo da Vinci into the fray. Hanging next to Massys’ duchess is a drawing of the same face by Leonardo’s favourite pupil, Francesco Melzi. It’s a copy of one of his master’s best-known grotesques, and from the ridiculous horned hairdo to the simian chin, it’s the same duchess.

Long before anyone had heard of the Mona Lisa, Leonardo was famous for his caricatures. These savage pictorial assassinations of men with hooked noses and pointy chins, and toothless old women with sagging jaws were circulating busily around late Renaissance Europe. In particular Leonardo seemed to have it in for Jews, whom he reduced nastily to big noses and hideous scowls. If he were working today, The Jewish Chronicle would be on to him fast.

Just as he enjoyed mocking Jews, so Leonardo took pleasure in drawing ugly women, and Massys’ duchess is revealed here to have been his exact invention. In circumstances that remain foggy, the image reached Flanders, where Massys copied it and developed it into his famous crone.

Having made that clear, the show sets about investigating how and why the late Renaissance enjoyed insulting old women. A trembly Florentine engraving from the 1480s shows a troupe of morris dancers circling another horn-headed ugly duchess who waves phallic sausages at them and holds aloft the penis-shaped hoof of a goat. She’s the old woman as a sex-starved witch, a regular brunt of misogynistic late Renaissance humour.

Another recurring subject of these sniggery times was the role played by money in the relationships between ugly old women and handsome young men. Israel van Meckenem’s 1480s engraving of an old woman seducing a young boy with money could pass for a lesbian transaction given how girlishly young Florentines liked to wear their hair.

The choice of examples is brilliant. Every exhibit brought in to expand the story of the Ugly Duchess is impeccably useful. An extraordinary ceramic bust of a toothless hag, so cartoonishly sparse in its outlines I had it down from a distance as something made recently in Naples, turns out to be a late 15th-century caricature from Faenza. Dürer’s thunderous engraving of a naked witch riding her broomstick through a gang of panicking Cupids is early evidence of the association of old women with satanic sex that was soon to result in horrific witch trials.

The most poignant of the exhibits chosen to enlarge the story of the Ugly Duchess is a tiny carving in pear wood from 1520s Germany. It too shows a naked old woman, sitting sadly on a bench, but this time the artist empathises with her nakedness and feels her sorrow. Folding her hands across her sagging body, the tiny old lady looks down at the ground, lost in memories. It moved me close to tears.

But we’ve forgotten our central couple. And left the meaning of their beautifully presented entanglement hanging for too long. Why paint them together? Do they like each other, or not?

The show never quite makes up its mind. A useful catalogue goes through all the possibilities without coming down firmly on any of them. Why Massys borrowed Leonardo’s crone and inserted her into this puzzling twosome is probably destined to remain a mystery. Here’s my ten pence on the subject. What’s clear is that Massys is going for laughs, and they are chiefly directed at the duchess. She is, indeed, one of the lusty witches-in-waiting described elsewhere in the show. Hence the enormous wrinkly bosom heaving over the edge of her bodice and the tiny rose she clutches in front of it.

He, meanwhile, is the beautifully painted straight man in the duo: the Ernie Wise to her Eric Morecambe. When you go to the show, lean in and admire the precision with which his wrinkled face has been captured and the miraculous detailing of his fur collar. The show introduces many subjects. The painterly skills of Massys is one of them.

The way he looks at her is a look of engagement. Their relationship may be loaded with deeper meanings, but on the surface it’s a positive one. She holds up her rose to him, and he’s responding. She’s got the money — her clothes tell us that — and that’s what he’s probably after. But look again at his raised hand. The one that is turned to us, not to her. See how the index and middle fingers are crossed.

The gestural history of crossed fingers goes back to the Crucifixion. At some point they ceased to be a sign of Christianity and began to gain their modern meaning as a gestural escape clause. He’s accepting her proffered rose of love, but he’s also crossing his fingers. And we are in on the cruel joke. It’s cunningly plotted, beautifully painted, intricately worked. We have here some top-drawer Renaissance misogyny.

The Ugly Duchess: Beauty & Satire in the Renaissance is at the National Gallery, London WC2, until Jun 11