I always tiptoe into exhibitions and always look carefully at the art — it’s the art critic’s modus operandi — but I admit I walked in extra lightly and stared with extra care at Souls Grown Deep Like the Rivers, a selection of works by black artists of the American South, which has arrived, somewhat unexpectedly, at the Royal Academy. So much is in play here, so many difficult lives, with such a blighted past.

The show’s arrival at the RA is unexpected because . . . well, you know why. Ever since it was founded in 1768 by George III, the RA has been a pompous organ of restriction and privilege in art. Looking down the list of exhibitors included in Souls Grown Deep, the RA’s first president, Sir Joshua Reynolds, would have thrown himself across the doors to the institution bellowing: “Never will you pass through these hallowed gates!”

Although not a slave owner himself, Reynolds fraternised with plenty who were, so the issues raised continuously and heartbreakingly at this emotional event applied directly to him, even if they would not have interested him overly.

But the pendulum of art inevitably swings back. Right now it is the artists who are gathered here who have the microphone, and it is the turn of the Sir Joshuas to stay silent and open the door. Which, to be fair to the RA, is precisely what it has done.

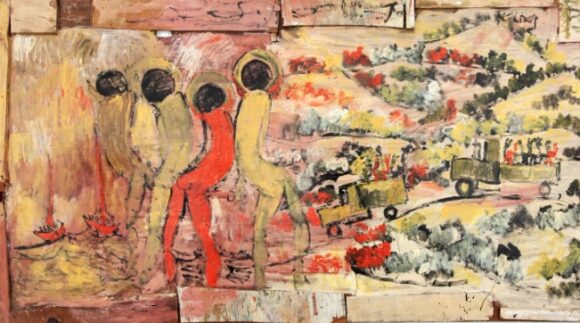

Taking its name from a famous line in a poem by Langston Hughes, a defining figure of the 1920s Harlem Renaissance — “My soul has grown deep like the rivers./ I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young” — the show brings together 34 artists from the American South, born between 1887 and 1965, who work in various styles and different media but who share one overwhelming truth: none of them had it easy.

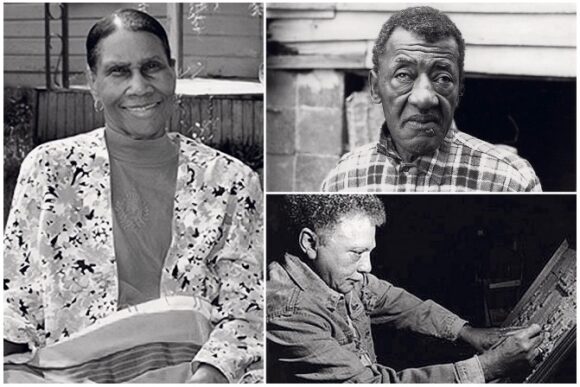

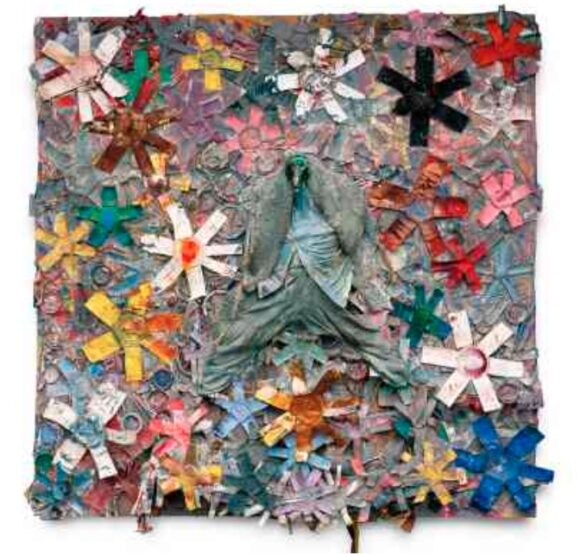

Hawkins Bolden, from Bailey’s Bottom, Tennessee, who makes poignant wall assemblages out of scrap metal picked up in the streets of Memphis, went blind at the age of eight after an accident playing baseball. “I don’t worry about colour. I know when I can make something by how it feels,” he explained.

Archie Byron, from Buttermilk Bottom, Georgia, a childhood friend of Martin Luther King Jr, wanted to join the police but he was too small. So he became a construction worker instead. The police bug, though, had bitten him fiercely and in 1961 he founded “the first black-owned detective agency in America”. Out of a mix of sawdust and glue, he fashions angsty reliefs in which symbolic men interact with symbolic women surrounded by symbolic bits of body.

Loretta Pettway is from Gee’s Bend, Alabama, home to a patchwork quilting tradition that dates back to the 19th century. She married a ne’er-do-well who drank and gambled. To keep her children warm, and to stop the straw in their homemade mattresses from pricking at night, she began sewing poignant quilts out of worn-out fragments of family clothes. String-Pieced Quilt, sewn in 1960, is shimmering and pale, mostly grey, with accents of startling blue, as if butterflies have fluttered across a rushing river.

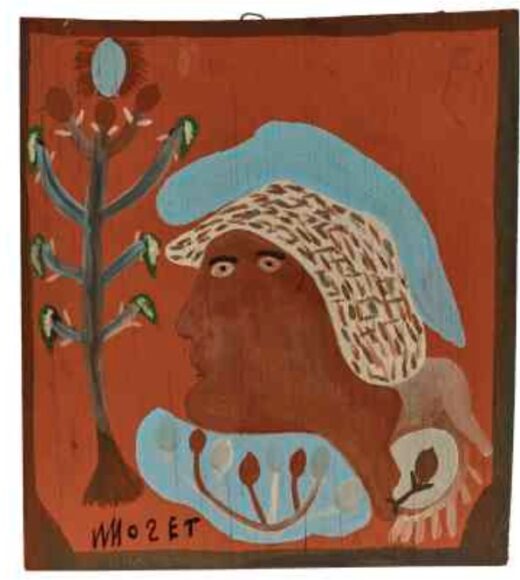

I could go on and on. Every artist in this affecting display has a life story full of difficulty. No one went to art school. Most barely went to school at all. Some became gravediggers, others armed robbers. Several joined the army. And underpinning all their individual sadnesses was the huge, shared, overwhelming sadness of slavery and its catastrophic impact on their lives.

Langston Hughes’s line about souls as deep as rivers hints with beautiful tenderness at something you feel everywhere in this gathering — a sense of loss; a yearning for origins that have been ripped away; memories that go back, back, back.

A few works make specific reference to the grim facts of slavery. Richard Dial’s Which Prayer Ended Slavery, from 1988, is a looming scaffold of welded steel on which we can make out angry white masters whipping their kneeling black workers.

Thornton Dial Jr’s King of the Jungle, from 1990, features the crude outline of a lion bashed out and welded from prison chains.

More often the laments are ambiguous. Lonnie Holley’s Copying the Rock, from 1995, features a clapped-out Xerox machine into which the artist has fed a big lump of stone. The point he’s making — that Xerox machines can never copy reality — is both a comment on the impact of technology and an admission of feeling out of place in a modern world that has no role for ancient rocks.

When the folk art of the Deep South was rediscovered in America in the 1980s there was a rush to shove it to the top of the pantheon. A show of Gee’s Bend quilts at the Whitney Museum in New York in 2002 was famously described by Michael Kimmelman in The New York Times as “some of the most miraculous works of modern art America has produced” and compared loudly with Matisse and Klee.

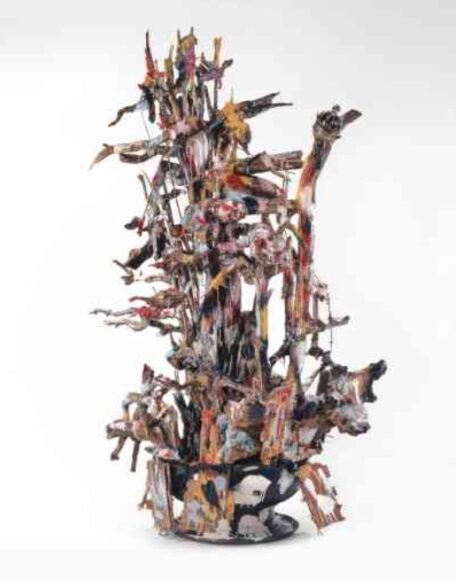

To me, those kinds of comparisons are shrill and even ludicrous. All the art here has powerful resonances. But not all of it is great art. Some of it is clumsy, lumpy, ham-fisted. Thornton Dial’s Tree of Life (In the Image of Old Things), a tottering assemblage of wood, old tyres, bits of wire, and plastic air-fresheners, made in 1994, is chaotic and ugly. Full stop. What all of the exhibits do prove, however, is the cultural necessity of art. You can take away almost everything from a human being — their freedom, their dignity, their happiness — but you can’t take away their creativity. Everything here is a flash of freedom, a reminder of art’s centrality in the human condition.

Freshened and enlivened by these important reminders, I skipped over to Alicia Reyes McNamara’s show at Niru Ratnam full of hope. It was exactly the right state in which to visit this bonkers psychedelic experience. Coming from a mixed Mexican and Irish background — hence the exciting name — Reyes McNamara has delved enthusiastically into the spirit myths that shaped both her parental cultures, and has emerged with a quasi-religious art that feels as though it has floated up like incense from an altar celebrating the union of Celtic and Mesoamerican goddesses.

Dreamy figures. Shifting waters. Staring eyes. Ten years ago, when the pendulum of art had swung in the opposite direction, these dippy paintings would have been booed out of the gallery as attacks on reason. Today they are right on the button and I loved them. Hare Krishna and all that.

Souls Grown Deep Like the Rivers is at the Royal Academy, London W1, until Jun 18. Alicia Reyes McNamara is at Niru Ratnam, London W1, until Apr 1