For proof of how rapidly tastes change in art, I recommend a visit to the unlikely pairing of Hilma af Klint and Piet Mondrian at Tate Modern. What a turn up!

Ten years ago this show would have been impossible. Five years ago it would have been improbable. Today it is fully on the button, so “on the button” it might even be described as “predictable”. The river of art twists this way and that, and right now it is flowing fiercely in the wacky direction of this unexpected pairing.

Af Klint was born in Sweden in 1862. Mondrian in Holland in 1872. The two never met. Their histories were dramatically different.

Until ten years ago hardly anybody in art had even heard of af Klint. In art historical terms, she didn’t exist. Everyone, however, knew Mondrian. He was a hero of modernism, a pioneering abstract painter who was there at the beginning and never wavered. Two fiercely different paths. What has brought them together?

The blunt answer is: hocus pocus. A belief in the supernatural and the arcane. Art is waging a war on reason: spiritualist beliefs that might previously have prompted guffaws are being described in hushed tones by a new generation of generous distaff art historians. Af Klint and Mondrian were both theosophists, followers of the fraudulent but extraordinarily influential Madame Blavatsky. In the past it would have been held against them. Not any more.

Theosophy was the Scientology of its time, invented by Blavatsky, whose magnum opus, The Secret Doctrine, was published in 1888. Full of cosmic diagrams and confused borrowings from other beliefs, the book proposed that all the world’s religions were actually one religion, and that underlying the chaos of existence was a universal truth that only the enlightened could see. Today we would dispatch Louis Theroux to India to interview Blavatsky. At the end of the 19th century, her ideas had powerful traction and played a crucial role in leading artists to abstraction. Notably af Klint and Mondrian.

The two of them duly find themselves sharing an engrossing show that is full of both marvellous work and preposterous gobbledygook.

We begin with some landscapes. Both Mondrian and af Klint were haunters of empty fields who liked to measure themselves against the hugeness of the earth. A beautiful early Mondrian of nature divided strictly into a big sky and a big plain has some specks on the horizon that turn out, when you lean in, to be a herd of cows. An adjacent af Klint landscape makes exactly the same point. Gigantic world. Tiny cows.

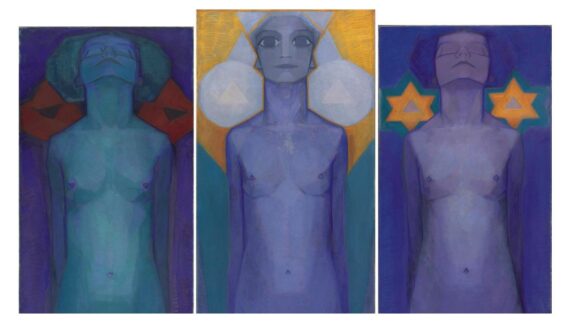

After softening us up with poetic landscapes, the event gets down to business with a gallery full of hardcore theosophist art. Painted in 1911, Mondrian’s Evolution is a creepy triptych featuring three purple female nudes in Mystic Meg poses of the kind you might find outside a fortune teller’s booth at the seaside.

Having embarrassingly revealed his true colours, he moves on quickly to abstraction, searching for universal order in the patterns of trees and simplifying the empty beaches at the theosophist retreat in Domburg into upper and lower stripes.

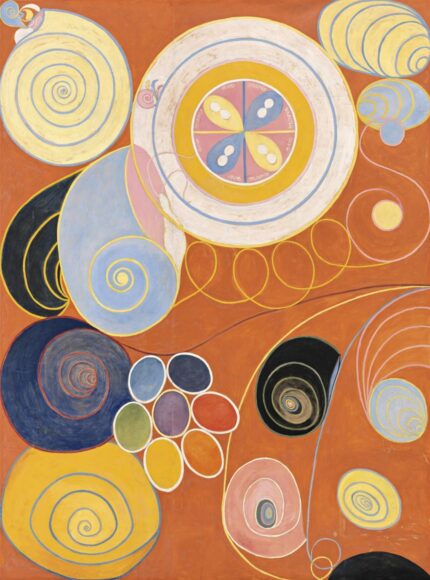

Af Klint, meanwhile, is more interested in Blavatsky’s wacky diagrams than the search for a universal truth. Her early theosophist art, in a sequence also entitled The Evolution, is a melange of interconnected symbols in which dogs turn into snails and dancing nudes hold up Christian crosses. Conspicuously nutty, it is the kind of work Harry Potter might have produced had he gone to art school instead of Hogwarts.

Watching af Klint become less clunky is one of the pleasures ahead. There are many of them. Cleverly paced and generously selected, the show grows ever more engrossing. Mondrian begins as the better painter, but it is af Klint who takes the bigger strides, her art becoming larger, simpler, less predictable. By the time we reach a suite of 1915 paintings called The Swan, where huge circles are divided into thrilling quadrants of colour, she is fully an abstract painter; probably the most radical such artist at work at the time.

Deciding who arrived first at abstraction is a popular boy’s game in art. Until the rediscovery of af Klint, the title was disputed by Kandinsky, Malevich, Mondrian — all of them theosophists of varying degrees. But it’s clear from the journey described here that as early as 1907 af Klint was already there, conjoining circles, spirals and dancing lines in gently coloured art with no precedents.

According to af Klint herself, this first abstraction wasn’t actually her own handiwork. Holding seances with a group of female disciples who called themselves the Five, she received messages from some superior beings known as the High Masters, and the art she made was their creation, not hers. As I said — nutty.

But it’s not that different from the works made by William Blake when he said he was visited at night by an angry angel. Or by Fra Angelico when the Christian God speaking through him inspired some of the most beautiful religious art of the 15th century. Whatever it was the High Masters whispered to af Klint led her to produce art of startling originality.

There is less to discover about Mondrian, although the inclusion of his flower paintings is an unexpected joy. Showing the two together is what makes this such a compelling journey. Thank heavens for yin and yang.

Hilma af Klint & Mondrian is at Tate Modern until Sep 3