Most of the trickiest questions in art are impossible to answer. Who’s the greatest painter of all time? Who produced the best landscapes? Don’t ask me. I haven’t a clue. Art is a universe of subtleties.

But there is one question to which not only I but everyone else in the art world immediately knows the answer. If you asked, “Who was the most squalid artist of all time?” we would respond with a unity that would shame a Welsh choir. “Soutine!” we would roar.

Chaïm Soutine (1893-1943) came from Belarus, but spent his creative years in Paris. Born into extreme Jewish poverty, he never allowed its textures to fade or its gloom to brighten. One good story about him is that he went to the doctor complaining of deafness, and the doctor found a nest of bedbugs living in his ear. Another time, he bought the carcass of a cow he wanted to paint and hung it in his studio. After several weeks it had rotted to a deep brown. So he started topping up the reds with fresh blood from the butcher.

Despite all this — or, perhaps, because of it — Soutine was a painter of extraordinary invention and subtlety. Yes, he painted with the kind of fury you feel when two dogs attack each other, but he was actually one of art’s finest colourists. While he was alive, he was too different to attract followers. After his death he began to be noticed. In America, the abstract expressionists owed everything to him. In Britain, Francis Bacon and Frank Auerbach were in awe of him. So too was Leon Kossoff (1926-2019).

To make this super-evident, Hastings Contemporary, that marvellous hotspot of aesthetic creativity located so interestingly on the East Sussex coast — past the pedalo pond, in between the fishing boats — has paired Kossoff with Soutine in a double bill that is both inspired and surprising. Bravo, Hastings. But who the hell came up with this crazy idea?

Hastings Contemporary is a venue that unfolds from space to space. It’s made for journeys. And what we have here is a journey that allows both artists to make their individual mark, but also to interact tellingly. First, a roomful of Soutine, then a roomful of Kossoff. Then more Kossoff and more Soutine. Plenty of clarity. Lots of dialogue.

The opener, a selection of Soutine’s landscapes, is worth the visit on its own. The finest are set in Céret, a dark little mountain town in the French Pyrenees that most artists of the era shot past at speed on their way to the sunny south of France. You can’t imagine Matisse delighting in Céret. But Soutine did.

The vertiginous views and tree-bending daily storms touched a chord in his troubled Jewish psyche. The paintings he made of Céret are as active as a swarm of bees. Staring into the chaos, you can just about make out bending trees, swaying houses, ascending paths. Everything is moving, as if its final form were still to be decided. And yet . . .

Lean into the picture, pause before one of its swaying details, and you will see paintwork of exceptional beauty and subtlety. Soutine may have worked at feverish speed, but the control was always there. He was to painting what Lionel Messi is to football or Muhammad Ali was to boxing: a high-speed perfectionist of remarkable dexterity.

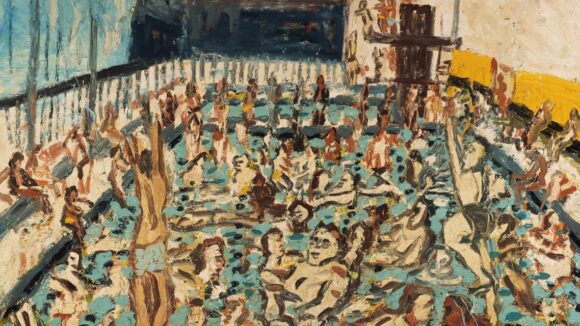

Kossoff was not. It’s harsh to brand him the weaker painter in this exciting match-up, but where Soutine is flexible and nimble, Kossoff is effortful and burly. Born in north London of Russian Jewish parentage, he too was a creator of art that feels soaked in pessimism. But the flaying paintwork with which he expresses the darkness often has a sense of hit and hope about it. Where Soutine works with a scalpel, Kossoff works with a trowel.

His first cityscapes of a bombed-out London after the war tempt us into imagining a doomy Jewish underpinning to the gloom. They’re so thick with encrusted paint they look as if they have been made from real mud and actual bits of broken concrete. I found myself wondering how much these slabs of pictorial tarmac must weigh. Lean into a Soutine, and the darkness lifts. Lean into a Kossoff, and it grows darker still.

Having compared them as landscapists, the exhibition moves on to portraits and figure painting. Neither artist favoured the rich or the prominent. Soutine painted cooks, bellboys and waitresses. Kossoff his wife, his children and his brothers. In both cases, the democratising of the portrait feels deliberate, as if a specific point is being made about who deserves to be painted.

Soutine’s unsmiling faces form an unhappy ring of humanity. Examined from the waist up, posed with zero variety, they stand glumly before us like suspects in a police identity parade. Yes, officer, it was the bellboy on the left who did it. The paintwork is, again, dazzling. But portraits will always have a more insistent psychological presence than landscapes. So Soutine the portraitist feels like the sender of bleaker messages than Soutine the landscapist.

Kossoff, on the other hand, grows more varied. His portrait of his wife stretched out nude on a red bed is one of the event’s high spots. She may be nude, but not one atom of erotic intent manages to free itself from the sombre picturing of her vulnerability and her discomfort. A snail has been been yanked out of its shell.

Soutine/Kossoff, at Hastings Contemporary until Sep 24