If you put a gun to my head, pushed me against a lamppost and demanded I name my favourite art movement, I would probably splutter: “Post-impressionism.” It’s the one that presses my buzzers most firmly.

My biggest buzzer, the macro buzzer, responds to the overall impact of a movement. The simple truth here is that post-impressionism was shockingly potent. It changed everything: led art away from all that came before and towards all that lay ahead. If you compare Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Bonaparte Before the Sphinx, from 1886, with Georges Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, also from 1886, you are comparing a penny farthing with the car Max Verstappen is driving in this year’s Formula One. It scarcely seems possible that the same era was responsible for both paintings.

Just as impressive is post-impressionism’s cast list. Was there another artistic moment when wizards of the calibre of Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Seurat, Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec were at work at the same time, in the same place, forging the same revolution? I think not. In its personnel and its impact, post-impressionism had a unique sparkle.

Not that the National Gallery in its tribute to the movement actually calls it “post-impressionism”. Perhaps that name was deemed too technical for today’s plebeian tastes? Instead, we get After Impressionism, with the appended subtitle Inventing Modern Art. Same truth. Different packaging.

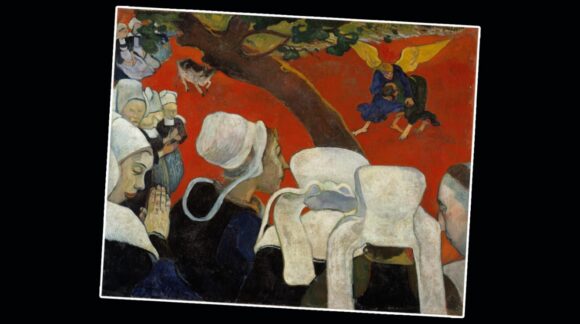

The beginning is truly thrilling. The big guns of post-impressionism have been given a wall or two on which to impress us and some fine loans have been called in. Cézanne’s gorgeous portrait of his wife in a red dress, the one in which he turns her into a modern Madonna oozing quattrocento calm, has been borrowed from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. A couple of joyously unfamiliar Van Goghs have been sourced from private collections. Best represented is Gauguin, two of whose finest works, Nevermore from the Courtauld Gallery and Vision After the Sermon from the Scottish National Gallery, sit at the centre of a riveting show within a show.

These days, Gauguin, the bête noire of identity politicians, gets remorselessly bad press. If you look at his art, however, rather than listen to his reputation, you see so much invention, courage, dynamism and sensitivity.

Why is all this different from what came before? Why is modern art being invented? The catalogue huffs and puffs in the search for answers before finally settling on the divergence we are witnessing here between art as a vehicle for description and art as a vehicle for conveying attitudes and emotions. Until the impressionists, the language of art was the language of visible reality. Post-impressionism changed that.

The most succinct example is Van Gogh’s Snow-Covered Field with a Harrow, painted in 1890. It’s a copy of a painting by Millet, of which Van Gogh had a black-and-white print. So the optics are given: an old harrow lies in an open field. But where Millet’s painting was set in autumn and is richly brown and fertile, Van Gogh’s copy is set in winter and feels cold and barren. Same scene, different meaning.

So we’re watching art liberating itself from the task of description. It’s a point well made with marvellous examples. Gauguin’s The Wave from 1888 has a poppy-red beach and a sea crashing on to rocks that are blue and purple. Yet it all feels right.

Unfortunately, this rousing start raises the bar so high and promises so much that everything that follows — the international spread of modern art — cannot help but feel like a drop-off. Also, compared with Cézanne, Gauguin and Van Gogh, the other big guns of post-impressionism — Seurat, Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec — are sketched in too lightly. Seurat in particular feels like an absentee from a storyline to which he was central.

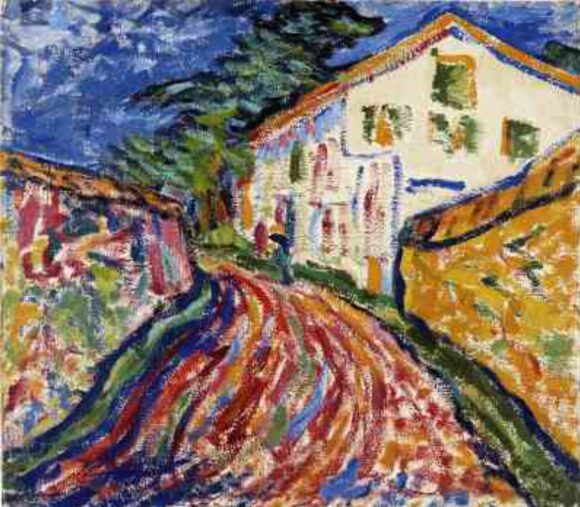

Ahead, the curators have chosen four “centres” where the revolution continued: Brussels, Barcelona, Berlin and Vienna. Each is given a room or an alcove in which to tell its story. In Brussels a group that called itself Les XX (The Twenty) was especially drawn to the lessons of the absent Seurat. They painted prettily with dots, but produced nothing that feels as radical as his work.

In Barcelona a group of progressives who frequented a café called Els Quatre Gats began painting melancholy portraits and moody street scenes in a manner that seemed to prefigure Picasso’s Blue Period. Indeed, Picasso himself was one of them!

In Berlin a gang of splashy realists, who seem to me to owe far more to Courbet than to the post-impressionists, took up discomforting nudes and angsty Germanic symbolism. On the universal sex-o-graph of patriarchal art, Lovis Corinth’s Nana or Max Slevogt’s Danae surely record nastier levels of machismo than anything by Gauguin.

The basic problem here is that none of the artists chosen to illustrate the spread of post-impressionism is as impressive as the movement’s originators. Had the show offered a greater wealth of detail and been more scholarly, it might have mattered less. But forced to race from location to location, it never settles.

That said, the ending with Picasso and Braque inventing cubism and Mondrian’s journey to abstraction is a lurch on to a higher plane. We seem once again to be in the presence of artistic giants.

So it’s a sandwich of a show. Good beginning. Good end. A muddle in the middle.

After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art, National Gallery, London WC2, until Aug 13