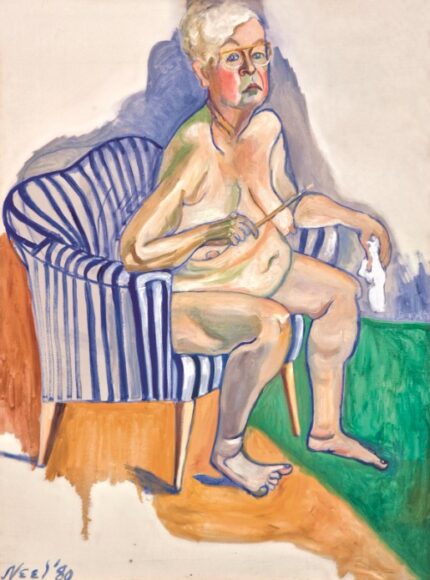

She’s 81 and as naked as the day she was born. Her breasts sag to her bellybutton, her stomach nestles on her thighs. She looks out at us sternly, like a grumpy German naturist daring us to disapprove. “Bravo, Alice Neel,” I mutter at the sight of this scary self-portrait. “That’s a hell of a way to start a show.”

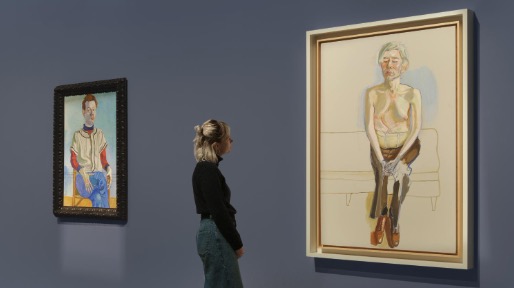

The Barbican Art Gallery is examining one of the most surprising careers in 20th-century American art. For most of her working life Neel (1900-84) was overlooked. Her misfortune was to coincide with the noisy, macho, attention-hogging triumph of abstract expressionism and to commit stubbornly to painting portraits at a time when it simply wasn’t a modernist thing to do.

Today, of course, not being a modernist is a badge of honour and her contribution is highly valued. So valued that I suspect nine out of ten contemporary curators would now pick her ahead of Pollock, Rothko and co in a vote to rank the most meaningful 20th-century careers. The pendulum of art keeps on swinging, and it has swung unstoppably in her direction.

This show’s curator, the estimable Eleanor Nairne, London’s best curator, has arranged Neel’s output in helpful chunks and made sure we note the parallels taking place between her art and 20th-century American history. Originally from Gladwyne, Pennsylvania, Neel was another of those artistic products of small-town America who couldn’t wait to get out. As soon as it was possible she fled, complaining she “couldn’t stand Anglo-Saxons . . . their soda-cracker lives and their inhibitions”. She tried the air force. That didn’t work. So she became an artist.

At a summer camp she met the Cuban painter Carlos Enríquez, who pops up here in an early portrait looking like an extra in a Humphrey Bogart movie: pencil moustache, slicked-back hair, a glass of rum in front of him. If she hadn’t met him at art school, she could have ordered him up from central casting as the non-Anglo-Saxon bad boy.

They married and moved to Cuba, where, of course, it quickly began to fall apart. Having been born in 1900, exactly on cue for the new century, Neel lived through dramatic changes in America’s social history, as well as lots of non-Anglo-Saxon husbands and lovers.

From the start she seems to have had a thing about nudity. As soon as she got back from Cuba and moved to Greenwich Village, in New York, she began painting her friends with their kecks off. The skinny Greenwich Village local Joe Gould is given a cornucopia of extra penises in a weird lurch into symbolism. In a startling 1935 watercolour her new lover John Rothschild is shown peeing into the sink while Neel uses the lavatory.

The conventional reading of this intimate imagery is that it reflects Neel’s hunger for honesty and her desire to see things as they are. But there’s something else going on: a visual bluntness, a cruelty, not unlike the confrontational directness of Lucian Freud.

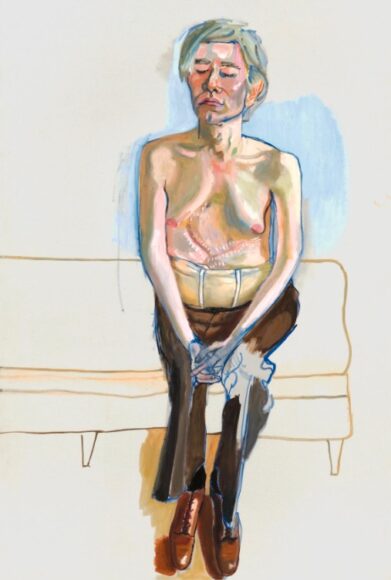

At the other end of her career, when she finally found her signature style, she would often insist on her sitters posing nude, notably in a celebrated series of pregnant women. Here too the results feel edgy rather than warm. Her masterpiece is a portrait of Andy Warhol after he was shot by Valerie Solanas. Poor shirtless Andy, displaying his scars, is as uncomfortable and pale as a snail that’s been yanked out of its shell. Neel was many things, but none of them was the jovial, grinning granny of artistic folklore.

One of the surprises of the show is how long it took her to find that signature style. Half the circuit here is given over to the search. In the 1920s she paints dark street scenes recording union protests against the government. In the years before the Second World War she paints angry mobs marching through Manhattan with banners that read “Nazis murder Jews”.

The ne’er-do-wells she keeps falling for — yanking them away from their wives and children — are alcoholics and drug addicts, brilliant but unsteady communist leaders and significant beatniks. Having joined the Communist Party, she gets investigated by the FBI. So she hangs a portrait of Lenin on her kitchen wall and never takes it down.

The nude self-portrait makes her rebelliousness entertainingly evident. Wilful, spiky, angry, louche, she seems always to be waging a war against propriety and authority. “What exactly are you rebelling against?” “What have you got?”, and all that. And while she’s fighting the Man, she’s inviting in every passing non-Anglo-Saxon stranger and painting them.

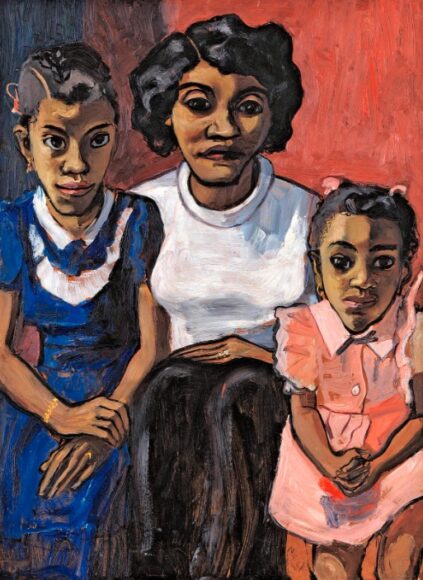

Hispanic mothers and their children. Black faces, brown faces, Asian faces. Girlfriends, boyfriends; sisters, lovers. People in Andy Warhol’s circle. Warhol himself. Anyone passing her doorway in Spanish Harlem seems to have been pulled in and briskly recorded. She called herself “a collector of souls” and certainly painted a lot of people.

As an output it feels taxonomic, as if she’s catching all the visitors she can and arranging them in types. Thus the show’s final pairing has Gus Hall, the leader of the American Communist Party, staring across at Annie Sprinkle, stripper, prostitute, porn actress. He’s wearing a bearskin hat and a strict Russian coat. She’s wearing high heels, suspenders and a kinky leather leotard from which her boobs have exploded.

Is this really the collection of souls? Or is it a poppy, dippy, bonkers American version of Soviet social realism? Today the jury is firmly on Neel’s side. Will future observers be as enthusiastic as we are? I have some doubts.

Alice Neel: Hot Off the Griddle, Barbican Art Gallery, London EC2, until May 21