Open any serious telling of the story of art, turn to the chapters on the Renaissance and you will find many pages devoted to the Florentine sculptor Donatello. He is one of the giants, the books insist, up there with Leonardo, Michelangelo, Giotto. So sure is the Victoria and Albert Museum of his rank that in the paperwork for its Donatello extravaganza it has called him “the greatest sculptor of all time”.

His dates (1386-1466) are certainly astonishing. At his death Michelangelo had not yet been born, and wouldn’t be for another decade. It was Donatello who finally matched the art of the ancients and produced sculptures as accomplished as anything made by the Greeks and the Romans. Put crudely, he invented the Renaissance.

As if that were not enough, he is also credited with bringing deep emotion to sculpture. The art of the Middle Ages had successfully mined such emotions before. But it was Donatello who found a way to continue the gothic moods while simultaneously exploiting the naturalism and harmony of classical art. Two great streams of western achievement were momentously persuaded to coexist.

That, at least, is the theory. And I have traipsed through many a dark Florentine church in search of evidence of these superb achievements — usually without finding it. The trouble with Donatello is that so much of his best work is so hard to see. At Orsanmichele in Florence his sculpture is displayed in niches high above the street. In the Basilica di Sant’Antonio in Padua it’s tucked away in unlit corners. Outside the church his gigantic equestrian statue of the mercenary Gattamelata — the first equestrian statue erected in Italy since classical times — is perched so high on its pedestal you need a stepladder to view it. At the Basilica dei Frari in Venice you need binoculars to inspect his forlorn Saint John the Baptist.

With these failed attempts behind me, I hurried to the Donatello blockbuster, the first British exhibition devoted fully to him, hungry for intimate contact, concrete insights and firm connections. Alas, they proved hard to find.

One problem is that the show is housed in the V&A’s flashy new exhibition spaces, where the art deco moods clash uncomfortably with the pious profundity of the Renaissance. Dior and luxury liners belong here. The Renaissance doesn’t.

The open-plan arrangement of the display also makes its route difficult to follow. We begin clearly enough with a superb marble David from the Bargello Museum in Florence, the handsome young hero standing astride the slain head of Goliath like a Premier League footballer eyeing up a free kick. But where to go next? It’s fuzzy.

Donatello trained as a goldsmith and the show wants us to notice quickly how precise his skills are and how inventively he translated the lessons of goldsmithery into sculpture. By adding enamel or gold leaf he would highlight key moments in his bronzes and give them a decorative oomph. It’s especially evident in the so-called Medici Crucifixion, where a packed scene of Christ’s death is made more legible by the targeted deployment of gold leaf.

Yet the Medici Crucifixion is located deep into the show when its story has gone off on another tangent. At the start, where Donatello’s technical wizardry is actually being discussed, the giant head of God that looms up enticingly before you, beaten delicately out of golden copper, is actually by Beltramino de Zutti. And the gorgeous enamel of the Annunciation that makes you wish you’d brought a magnifying glass is by Ugolino di Vieri. Before we have a picture of the man himself, we are already dealing with the artists that he influenced.

It’s bad exhibition-making. At his own show Donatello is too often the invisible man. A row of reliquary heads — sculpted busts containing the relics of notable saints — tries to make evident his impact on portrait sculpture. The faces are, indeed, unusually realistic. The Renaissance has gone all truthful on us. Wow. But only one of the characterful heads — the one in the middle, a bronze bust of Saint Luxorius — turns out to be by Donatello. The rest are by his successors.

More tangibly he is presented as the inventor of a technique called stiacciato, a delicate form of shallow carving that allowed the sculptor to suggest great depth while removing onlya thin layer of stone. The V&A is lucky enough to own the prime example of this ethereal skill, a marble relief of the Ascension carved so lightly it might almost be the handiwork of a spider. Suddenly you come face to face with a touch like no one else’s.

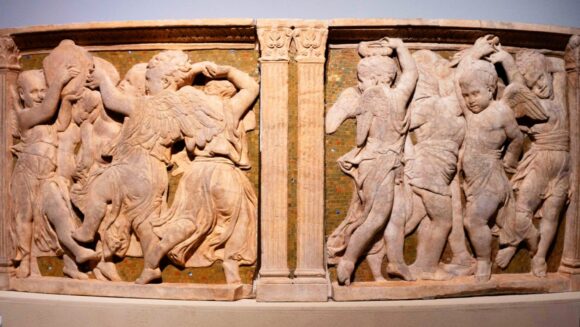

Another success is the celebration of Donatello as a creator of spiritellos, angelic little cupids who pop up all over his art and fill it with sprightly moods. The Duomo in Prato has lent one of the show’s highlights; a pulpit he began making in 1434, in which a crowd of dancing imps, who seem to have escaped from a nearby nursery, set about destroying the gothic solemnity of the early Renaissance.

He was also the inventor of the canoodling Madonna and Child: the ubiquitous Renaissance image of Mary and Jesus locked in a sacred hug. The pairing became so common it’s easy to forget that someone needed to originate it. The Pazzi Madonna, lent from Berlin, is especially warm-hearted, the infant Jesus pressing his forehead against his beautiful mother in a joyous marble search for the skin-on-skin experience.

If you get stuck into this display, there’s plenty to enjoy. Recurring glimpses of Donatello’s heightened skill. A valuable widening of our image of him. What we never get, unfortunately, is his clear outline.

Too many of the catchiest exhibits turn out to be the handiwork of someone else: “follower of Donatello”, “probably by Donatello”. To cap the confusion, the show’s final section deals with the copies and forgeries of his work churned out in the 19th century. The V&A is well stocked — overstocked! — with examples of these lookalikes. I can see why the museum might wish to make a virtue of them. But it creates further confusion.

For more solid evidence we need to have his magnificently sexy bronze David, the first lifesize nude created in Europe since Roman times, brought over from the Bargello. Sadly that is never going to happen.

Donatello is at the V&A, London SW7, until Jun 11