Some things in life are just not meant to go together. Oil and water spring immediately to mind. As do oysters and peaches, Kim and Kanye, denim and denim. It’s true, as well, of football and art. Forces bigger than us have ordained that football is one thing, art is another thing, and the two should not be mixed. That, at least, was the frame of mind I was in when I sat down to watch Match of the Day last weekend.

If you, too, saw the highlights of Tottenham Hotspur v Leeds United, two things would have surprised you. One was Harry Kane’s opening goal for Spurs being allowed to stand despite a blatant foul on the Leeds goalie. The other was the words “We Believe in Us” written luridly in yellow on blue, popping up on every video screen in the stadium as the winning goal went in (see below). “That’s a Mark Titchner,” I gasped, elbowing my wife in the ribs. “What’s he doing on Match of the Day?”

It’s a good question. Titchner, who was nominated for the Turner prize in 2006, is a familiar presence on the contemporary art circuit. In 2020, in the early weeks of Covid’s death spree, you may remember him blasting out the comforting thought, “Please Believe These Days Will Pass” from poster sites up and down the land. He even unveiled them for us in a giant version inside Southwark Cathedral.

Encountering Titchner outside the art gallery is, therefore, no surprise. What’s astounding is seeing his produce at a football match. What’s more, an exhibition of his work has opened at the first contemporary art gallery in Europe to be located inside a football ground, the Oof Gallery at the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium. In the words of Peter Kay, ’ave it.

Why are football and art such unlikely bedfellows? As the most popular sport in the world — an international religion — football ought to be, if only by the law of averages, a frequent art subject. But it isn’t. And never has been. Indeed, sport in general has been conspicuously missing from the art catalogue.

Thinking back to my schooldays, I remember a clear divide between sporty types and arty types. The sporty types were good at football, confident of their looks, good at chatting up girls. The arty types were bad at football, unsure of their looks, good at writing poems about girls. One breed acted. The other breed dreamt.

If you examine football’s rare appearances in modern art, it’s noticeable how firmly this divide holds true. To take an obvious example, LS Lowry’s Going to the Match, painted in 1953, described as “the finest football painting in the world” by Gordon Taylor, the former chief executive of the Professional Football Association, isn’t really a football painting. In typical Lowry fashion, it’s a soppy picturing of northern life with hundreds of matchstick men pouring into the old Bolton Wanderers ground while the surrounding chimneys belch thick smoke. The only thing football actually brings to this endearing piece of grim-up-north poetry is the location.

Back at the start of modern art, a few futurists and suprematists had a go at depicting football players in action, but only because football seemed, like fast cars and electrified cities, to be an example of global progressiveness. When the great Italian futurist Umberto Boccioni painted Dynamism of a Soccer Player in 1913, he made sure his audience could not actually see what he was showing them. The abstracted flurry of chaotic shapes and swirling protrusions could just as easily be a top view of a tornado or Tom scrapping with Jerry. What Boccioni is really after is the sensation of breakneck speed, and not even Ronaldo was as fast as that.

The one time football did play an obvious role in the aesthetic wars of the early 20th century, in Russia in the 1920s and 1930s, it ended up on the “wrong” side, which is to say on the side of Stalinist social realism rather the pioneering modernism of the Russian avant-garde. Alexander Deineka’s celebrated Goalkeeper of 1934 — think Jordan Pickford diving full length to parry an Ivan Toney penalty — is one of a clutch of sporty paintings by the artist with a deliberate ambition to praise the active outdoor life of the Soviet worker and compare it with the housebound inaction of the Soviet modernist. The body v the mind, once again.

Russian health propaganda aside, it really is remarkable how little football there is in modern art. Among the giants of the field, Dalí paraded himself as a Barcelona fan and could sometimes be found holding a Barça ball. But it never felt like more than posing. When in 1965 Picasso produced his cute sculpture Footballeur, showing a poetic blob in kicking mode, he was way past his creative best and more interested in raising a smile than the game.

On the way to Titchner’s show, squashed into my seat on the 149 bus, I dredged my memory for examples of genuine artistic engagement with football and could only recall two. The first was the extraordinary effort of Nicolas de Staël, usually a painter of abstracted landscapes, who went football mad in 1952 and produced a series of slabby portrayals of France v Sweden at the Parc des Princes. One game, 25 paintings, widely considered to be de Staël’s masterpieces. In 2019, the final scene in the series sold for €20 million.

While de Staël, in the 1950s, appeared to be chiefly interested in the visual impact of the kit, the German painter Wolfgang Koethe spent the 1980s viewing sport as a stand-in for war. His snooker players were snake-hipped assassins prowling round the baize. His American footballers were modern versions of medieval knight in armour. And his soccer teams, notably his paintings of England v Germany in 1966, were divisions of faceless soldiers lined up neatly before the battle commenced. With Koethe, the artistic interest lay not in football per se, but in the symbolic window it seemed to open.

Something similar is going on with Titchner’s art. The Oof Gallery, in a small Georgian house that could not be knocked down for planning reasons when the £1 billion Tottenham stadium was built round it, is already a mini masterpiece of architectural surrealism: the least expected contemporary art gallery.

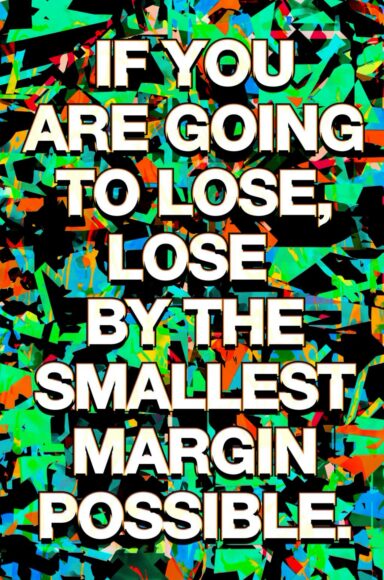

Inside, Titchner has had a go at capturing the emotional impact of football with an installation consisting chiefly of his trademark word art. “Envy the Success of Others,” says one wall. “Be Strong in Small Things,” says another. “If You Are Going to Lose, Lose by the Smallest Margin Possible,” advises a giant poster.

These bleak mottos, found in coaching manuals and adapted, seem to home in on the recurring disappointment of football rather than the occasional successes. Titchner, therefore, knows what he’s talking about. His poignant exhibition title, It’s the Hope That Keeps Us Here, says it all.

By the way, what time does the World Cup start?

Oof Gallery is free and open to all, oofgallery.com