The National Gallery used to have a handy format called Painting in Focus. Taking a single picture from the collection, the gallery would examine it from many sides, deepening and enlarging our understanding of it. It did it with The Ambassadors by Holbein, Madame Moitessier by Ingres and Bathers at Asnières by Seurat.

So the news that the gallery is reviving the approach under the new format name of Discover is to be welcomed. And by making Manet’s portrait of Eva Gonzalès the first picture to be examined in this old-new fashion, the National has made a stimulating choice.

Painted in 1870, it’s a puzzling image. It looks like one thing, but turns out to be another. When she met Manet, Gonzalès was a young art student, the daughter of well-to-do parents who supported her desire to be an artist. First, she studied under the run-of-the-mill society portraitist Charles Chaplin. Then she met Manet and studied under him — the only pupil he ever had. She was 20. He was 37.

Soon after they met, Manet began the painting in question. It’s a huge canvas, over 6ft tall, with obvious ambitions to make an impact. Looked at casually, it could pass for a predictable society portrait — young woman in beautiful white dress dabs away at a new painting. But the more you look at it, the stranger it grows.

If she’s an artist in a studio, why is she wearing that gorgeous white evening gown? Think of the splatters! If the picture she is painting is a new one, why is it in a posh frame? Frames are things you put on a painting after you finish, not while you are painting it. Why is she so far from the canvas? Why is her hair so unruly? Question follows question.

Having prompted us to ask, the show begins answering, although not always in an obvious manner. As a narrative, its route is jumpy, skipping from focus to focus in a cut-and-paste fashion that is now de rigueur in exhibition-making.

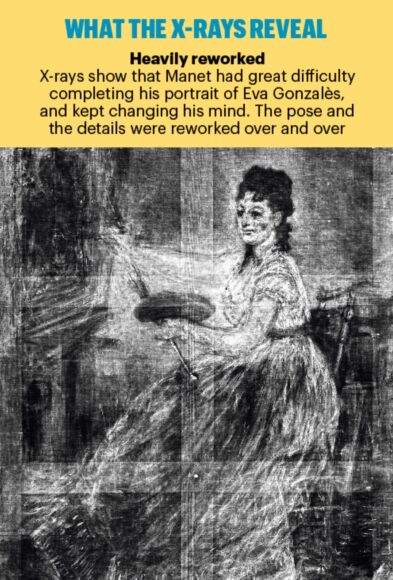

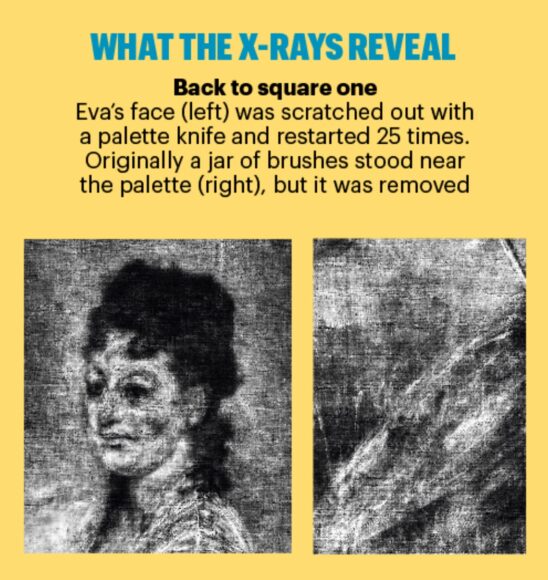

First we learn about its Irish connection, a tortuous ownership story too long to repeat, but which concluded with the National Gallery sharing the painting with Dublin City Gallery. Then we learn about how difficult it was to paint, with a fascinating technical analysis featuring x-rays and colour samples. Then we find out that the still life Gonzalès is painting was actually copied from a book illustration by the famed French flower painter Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer. And only then, at last, do we discover what Manet was really up to in this sneaky picture.

Eva Gonzalès is not just a portrait. It isn’t even mainly a portrait. What it mostly is is an attempt by Manet to update one of art’s venerable old master themes: the portrayal of La Pittura as the embodiment of Painting. From Renaissance times, Painting was symbolised in art as a young woman before an easel holding a palette and brushes. She wears a flowing dress. Her hair is unruly because the artistic spirit is unruly. Perhaps the best-known image of La Pittura is Artemisia Gentileschi’s masterpiece in the Royal Collection, featuring a woman painter in a green dress, which may or may not be a self-portrait.

So what Manet is doing here is tackling an old master subject disguised as a scene of modern life. It’s what he did when he painted a reclining Venus and called her Olympia. It’s what he did when he reworked Raphael’s river gods and called it Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe. This is Manet taking on the old masters. No wonder he struggled to get it right, repainting Gonzalès’s face 25 times before he was satisfied with the mix of accuracy and symbolism.

In truth, the National Gallery could have told us what was happening here a mite more straightforwardly. But having entered the tricky contemporary terrain of “male artist using younger female model”, the display feels compelled to fight the distaff corner. A show within a show has been added that looks at the way women artists have portrayed themselves in their self-portraits. We get fine examples by Laura Knight, Gwen John and Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun. They are exciting to encounter, but seem to be about something very different from what the Manet is about.

Something else that is missing is a decent sample of Gonzalès’s work. The show is keen to stress that she was a considerable artist in her own right who deserves more respect than she has generally received. It’s an important point to make. But the couple of examples we have here are not enough to make it.

Discover Manet & Eva Gonzalès, at the National Gallery, London WC2, until Jan 15

Hair-raising sex

Daring and unusual, the priest turned artist Fuseli’s work is carnally obsessed

Fuseli and the Modern Woman: Fashion, Fantasy, Fetishism is quite a mouthful as a title. Almost as much of a mouthful as the supine chap is getting in the startlingly explicit orgy scene hiding here under the guise of Three Women and a Recumbent Man. If you ever need pictorial evidence of there being nothing new under the sun when it comes to sex, consult Fuseli’s prickly drawing of 1810.

Born in Zurich in 1741, Henry Fuseli came to Britain in 1779. Made his home here. Got to the top of the tree as keeper of the Royal Academy. And turned himself into a notorious artistic presence, famed for his scenes of the supernatural.

Ever since I learnt that he wanted originally to be a priest, and went as far as to take holy orders, I have suspected that Fuseli was a few slices of Emmental short of a fondue. Fashion, Fantasy, Fetishism at the Courtauld Gallery backs me up.

It starts with a room devoted to his obsession with women’s hair. Most of the drawings feature his young wife, Sophia, gazing at us coquettishly while sporting a succession of increasingly outrageous follicular showstoppers. Hair rising up in a phalanx of phallic bulges. Hair twisted perkily into projecting horns. Hair arranged in precarious piles of corn rows. You will not have seen hairstyles or drawings like these before. What in the Marquis de Sade’s name are they about?

To complicate matters further, the next room is devoted to Fuseli’s depictions of courtesans, one of whose identifying features is not wearing many clothes. The other is the sporting of increasingly outrageous hair creations. Why would the Rev Henry Fuseli give his wife the attributes of a sex worker?

It’s probably best not to know. If you hold your nose and block out the stink of intense Georgian decadence, the outlines of a highly unusual artist start to become visible. His compositions are daring and new. His touch can be exquisite. Some of the crazy hairstyles he comes up with are wonders to behold.

That said, only rarely have I left a show as nonplussed as I did here. The words of Tim Burton spring to mind: “One person’s craziness is another person’s reality.”

Fuseli is at the Courtauld Gallery, London WC2, to Jan 8