Only rarely have I exited an exhibition having learnt as much as I learnt from Hieroglyphs at the British Museum. It’s the perfect show — deep, fascinating, full of beautiful things, full of beautiful ideas. While so many exhibitions get bogged down in narcissistic identity issues and evening-class politics, this one is driven by that utterly commendable old-fashioned aim: the pursuit of knowledge. Bravo, British Museum.

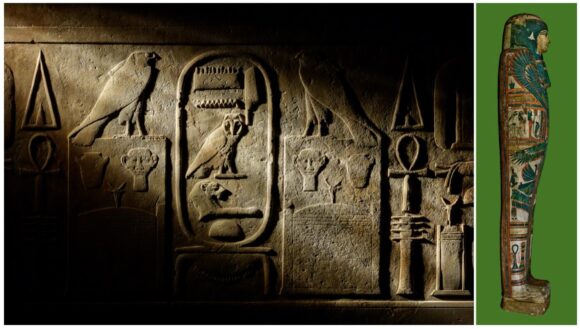

What is it about hieroglyphs? Why the pull? Why the romance? In a smart piece of exhibition stagecraft, the BM begins its investigation with a gripping object that pressed my art button and my knowledge button, and did it so violently I kept returning for another dose: the temple lintel of King Amenemhat 111.

This huge slab of sculpted hieroglyph originally loomed over a temple entrance guarding the approaches to Amenemhat’s funeral pyramid. It declared his name and lauded him for his cosmic import. And it did so with a cluster of signs that make clear why hieroglyphs are so damned intriguing.

In the centre, a mysterious owl turns its head towards us and stares. Flanking it, two regal falcons seem — to my unenlightened eyes — to be standing guard. On the right, a crocodile says something big. On the left, one of those mysterious crosses with a looped top whispers something secretive and a tad scary. Then a face. Then a pyramid. Then a temple front.

These looming mini-sculptures, carved gracefully into a rectangle of limestone, proclaim their meaning in a script that manages simultaneously to be artistically glorious and totally baffling. No wonder men went mad trying to decipher the hieroglyphs. They look like they are telling you something crucial. But no amount of ecstatic staring reveals what it is. At least, it never used to…

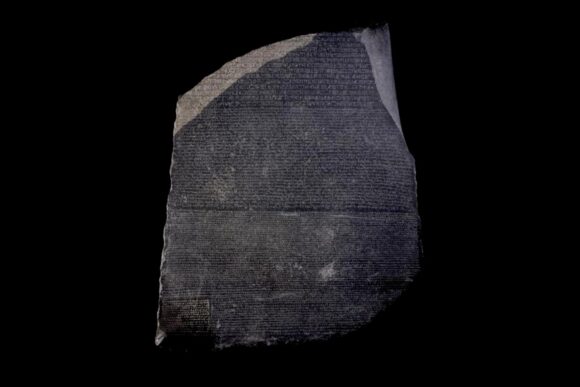

How the code of the hieroglyphs came to be cracked is the central subject of this superior event. Centred on one of the British Museum’s signature exhibits, the Rosetta Stone, the show runs us through the enthralling shaggy dog tale that is the decipherment of the hieroglyphs while using the opportunity also to plunge us into the infinity pool of ancient Egyptian history.

To begin with, hieroglyphs really were a picture-based sign language. Which is to say that certain signs in nature came to stand for certain words: a disc stood for the sun, a heart stood for passion etc. But as this pictorial language grew, the accumulation of signs became gigantic and unusable. So a process of simplification commenced. Signs were shortened. Symbols were broken into bits. Abstraction set in. Until the original pictographs were turned into a working phonetic alphabet.

Hieroglyphs look like pictures, but are actually sounds. However — and this is where it gets fascinating — some of the signs, such as the falcon or the owl, remained pictorially legible. So for 2,000 years, any unenlightened witness staring at them assumed they were looking at some magical ancient wisdom preserved in a pictorial script. Hence all the crazy magical Egyptology that the show begins to enjoy in a section devoted to the discovery and spread of the hieroglyph.

Islamic scholars saw them as the language of spells. The Italians sought to harness their divine power by erecting obelisks in squares and incorporating them in fountains. Alchemists began using hieroglyphic incantations in their failed attempts to turn base metals into gold. Basically, the world went hieroglyph-crazy. And fuelling the craziness was a universal ignorance of their actual meaning.

Enter the Rosetta Stone. Cleaned and elevated for this occasion, it sits at the centre of the exhibition like a looming idol in a temple. Discovered in 1799 by French soldiers sent to Egypt by Napoleon, it features the same royal text inscribed in different versions of ancient Egyptian and Greek. By comparing one with the other, scholars were finally able to crack the code of the hieroglyphs.

Not immediately, though. It took 22 painful years. The middle of the show is given over to a step-by-step account of a mighty linguistic struggle that ensued between the French Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion and the English archaeologist Thomas Young to solve the hieroglyphic mystery. The eureka moment came when Champollion focused on the make-up of the royal names cited in the Rosetta Stone and realised that the scripted alphabet depended on sounds rather than pictures. (At least, I think that is what happened. The linguistic exploration here is high above my pay grade, so forgive me, Egyptologists, for any errors.)

This, then, is a show that has been handed one of the hardest tasks in exhibition-making: how to turn a plethora of words and ideas into a pleasing and stimulating art journey. The curators do it brilliantly by adding the sugar of a dizzying array of Egyptian artworks to the medicine of a resolutely ambitious linguistic discussion.

Huge chunks of Egyptian fresco tell the story of imperial battles and pharaonic campaigns. Gorgeous basalt torsos are inscribed with mysterious health spells. A giant phallus wrapped over the head of a tiny Egyptian munchkin exhorts the gods to help the munchkin with his fertility.

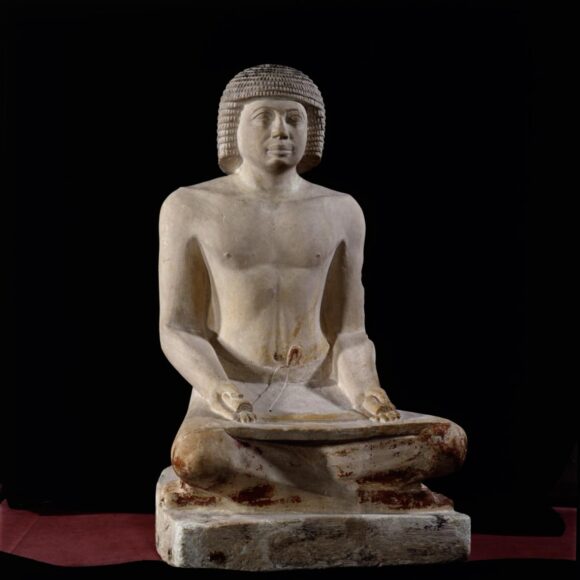

This feast of exciting fragments grows especially informative in the show’s final section where we watch the hieroglyph being put to common use in everyday Egyptian life. Hieroglyphs appear in love poems. In farm accounts. In school texts and legal documents. After seeing them for so long as the exotic preserve of necromancers, kings, alchemists and magicians, it’s good to see them finally being outed as something quotidian: the humble hieroglyph.

Hieroglyphs, at the British Museum, until February 19