Last week was the week of the Frieze art fair — “the most important week in the contemporary art calendar”. So I did what any true art lover would do and gave this monstrous souk a wide berth, thereby avoiding the invasive tents, the snooty doormen, the “important collectors” imported from Florida, the £20 glasses of champagne, the gallery frenzy, the aesthetic mess. Instead I did a round of new shows in London and confirmed that we really are living through a special moment in figurative painting.

Amy Sherald, at Hauser & Wirth, is best known for producing the official portrait of Michelle Obama, the one where the former first lady pops out from the top of a huge expanse of dress like an inquisitive turtle. When that painting was unveiled, I was unkind about it — too quick to rush to judgment to realise that you have to see Sherald’s art in the flesh to recognise its many subtleties.

The new works gathered at Hauser & Wirth fall into two categories. First there are the “portraits”, three-quarter- length views of single figures, a format with a long tradition in western portraiture except that in this case all the sitters are black. Strikingly and profoundly black. Thus, a tradition is being simultaneously enlarged and challenged.

Sherald’s signature gesture — the thing that makes her work stand out immediately on the shelf — is the use of grey paint for her flesh tones. Her sitters are unmistakably black, but to evoke their blackness she paints them with grey skin. It’s an aesthetic decision that seems puzzling in print, but not when you stand in front of it.

In the flesh, the grey tones look right and fit naturally because Sherald is, above all, a daring colourist. Her portraits are full of high-risk colour decisions — the clothes, the jewellery, the backgrounds. And to foreground these novel colour balances she needs to background the skin tones. It’s a brave artistic strategy, and it leads to exceptional art.

The sitters are never named. It’s just them, their clothes and their mood. A woman in a white dress with her hands clasped gently in front of her seems thoughtful and somehow religious, as if she’s got a fine voice and sings in a choir. A man in a green jumper with the number 22 on it isn’t shaped to be an athlete, he’s shaped to be an athletic fan.

The portraits pull you in and make you imagine things about this modest but gripping cast. It’s what great portraiture has always done. The jewellery tells you things. The clothes tell you things. The postures tell you things. And all the time, black presences that might otherwise be lost in the Niagara Falls of passing time are pulled out of the torrent, framed, treasured and respected.

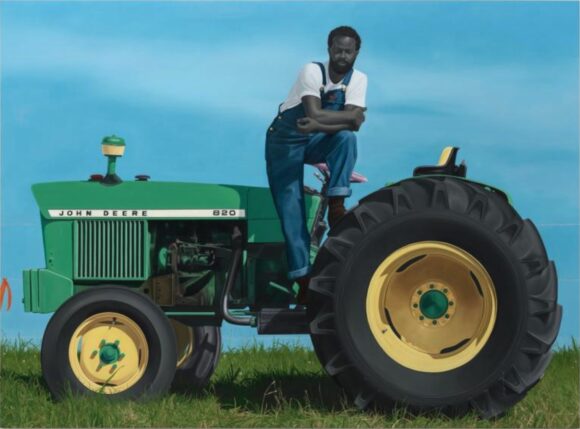

In her other mode, Sherald paints big canvases with historic ambitions; Napoleon- sized art that seeks to comment on the black presence in America — the same black presence that is missing so glaringly from American art.

A black farmer — painted again in Sherald’s signature grey — sits atop a battered tractor in a scene with a dust bowl mood. Flat land. Big sky. Hard-working farmer. Hard-working machine. It’s the kind of clichéd image of rural stoicism that is usually reserved for the heroic white farmer. By making him black, Sherald elbows some truth into an aesthetic lie.

She does the same with two black motorcyclists, riding their rearing bikes like the Lone Ranger on his white stallion. This is an exceptional show — inventive, beautiful, skilled, hard-hitting.

At the Maximillian William gallery, Somaya Critchlow, another black woman painter, confirms that her corner of the art world is on a roll and demanding to be heard. Critchlow, who is from London, tackles black identity more ambiguously than the New Jersey-based Sherald. Critchlow’s art is hazier, gentler, smaller, its relationship to blackness harder to read. Although here, too, there’s a sense of us v them.

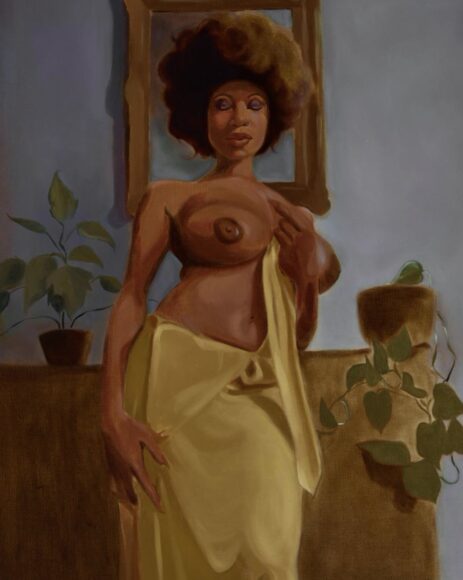

Her main subject is the black female nude. Indeed, on this evidence, it’s her only subject. Walking into her show, you find yourself ringed by a harem of big-breasted black Amazons, every one of whom seems keen to confront whatever you are with whatever they are.

The point being made, I intuit, is that western art is full of nudes — but they are all white. Here, therefore, are some black ones to rebalance the scales. And as most of the nudes appear to be Critchlow herself, we are simultaneously tugged into an intimate identity discussion that left me feeling a mite nervous.

A woman in stockings lies on a bed and pleasures herself. A woman in a yellow dress unties her top and lets it drop, then stands there for you to inspect her. A naked woman leans on a wall by a window and strokes a cat, while the moon outside seems to smile.

The knowledge that some or most of these twilit figures represent Critchlow takes the art out of the shouty political arena and into a secretive, poetic one. But in a reversal of the usual dynamics of the ubiquitous art nude, the desires flow out of the canvas and into the visitor space. Usually it’s the other way round. What I think is going on — and excuse me while I tread extra carefully — is that the artist is trying to share feelings of feminine empowerment, yearning and excitement that have not previously been shared in art. The feelings are specific to a black self-image. But, in enlarged form, they speak of the feminine psyche in general.

Critchlow isn’t in the Amy Sherald league as a painter. Technically, she’s less distinctive. But her art arrows in on nervy places and it certainly leaves you thinking.

Amy Sherald, Hauser & Wirth, London W1, until December 23; Somaya Critchlow, Maximillian William, London W1, until November 19