It falls to few artists to change the course of art. You can count the ones who have done so on one hand. Art was one thing before Michelangelo came along, before Caravaggio, before Duchamp. After them it was another thing. So it was too with Cézanne.

Tate Modern’s flawed but engrossing survey of his achievements is packed with gripping evidence of his difference: his genius. Put crudely — very crudely — Cézanne freed painting from the task of describing things and started it on a path to thinking about them and feeling them. His pictures stopped being mere descriptions and started becoming profound events. He led to Matisse, to Picasso, to Mondrian. And beyond them to abstraction and conceptual art.

Spend 15 minutes in front of his beautiful portrayal of Madame Cézanne in a Yellow Chair and you will be hypnotised into a connection with the image that takes you close to the world of dreams. Her calm, her gentleness, the unsolvable mix of soft and hard in her seemingly simple but actually complex expression, glide the painting past your eyes and deep into your instincts.

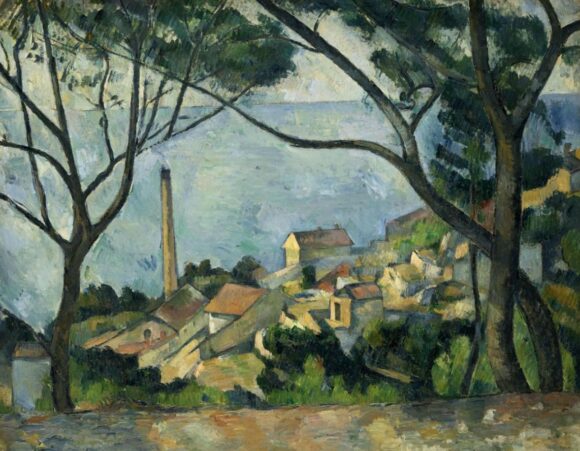

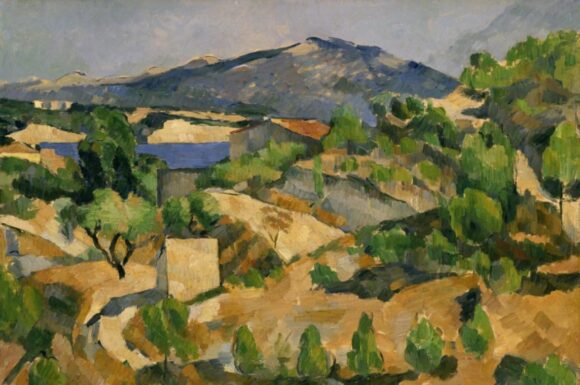

His landscapes are the same. If you give them time they press your mindfulness button more firmly than any landscape art has previously pressed it. A picture like The Sea at L’Estaque Behind Trees, which used to belong to Picasso, sends your gaze on an optical treasure hunt, enjoying not only the cubistic houses on the sea shore, and the interplay between the trees and the sky, but, most tellingly, the miraculous interconnectedness of everything you are looking at. In a great Cézanne, foreground and background, land and sea, horizon and tree give up their separation and interlock in a transportative shimmer.

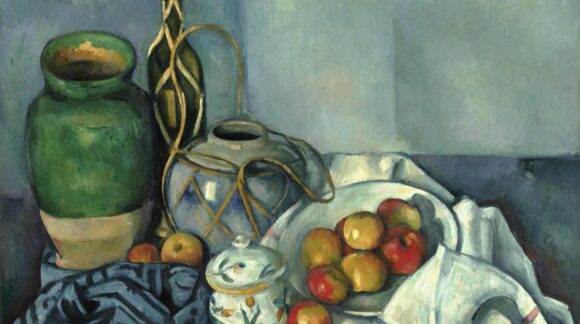

Then, of course, we have his apples. “I will astonish Paris with an apple,” he famously bragged. In the Getty Museum’s Still Life with Apples he manages to make something stormily exciting out of a loose arrangement of apples and pots on a table. It’s just apples and pots. But the energy pent up in that cascading table would sit happily in a view of Niagara Falls.

This is more than optics. Cézanne didn’t just paint the world differently, he felt it differently too. There’s an ecstasy to his vision, a sense that what he is trying to convey is the buzzing of his heart when he looks at Madame Cézanne; or the intoxicating summer calm that descends on him when he dab, dab, dabs away at a view of the Mediterranean on a light-filled coastal day at L’Estaque. The cicadas are in full voice. You can’t see them. You can’t hear them. But you sense their unceasing chirping.

Ecstatic mystery is, of course, beyond the usual scope of a Tate Modern exhibition. Having gathered a treasure trove of boundary-testing art, the show seems nervously unsure what to do with it. Cézanne is too big, too profound a subject for the Tate to tackle convincingly in its present mindset.

So we end up taking a wobbly route through his achievements with a trademark Tate mix of variable chronology, slippery themes and the hopeful projection of contemporary social obsessions on to his art. The apples get a niche. The landscapes get a niche. The bathers get a niche. And so does a newly imagined political progressiveness in Cézanne’s art.

A ridiculous caption for one of the show’s masterpieces, a shimmering view of a forest glade borrowed from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, is devoted to colonisation and its impact on the painter. “I wonder what this landscape would have looked like to us without colonisation,” writes a befuddled Rodney McMillian, jackhammering his own obsessions into Cézanne’s thinking.

It’s an approach that blinds the show to truer truths about Cézanne. We don’t get a tangible sense of his development. The wonky chronology leads to his eras being jumbled. His early art, the pictures painted in his “manière couillarde”, his “ballsy” style, shoot through at Lewis Hamilton speed. Which is a shame because their awkwardness and blackness might have pointed the event in a telling direction.

Cézanne was a devout Catholic. In the latter stages of his life he went to Mass every day in Aix Cathedral, where the stony elongated saints in the portal and the leaning gothic of the architecture inspired a desire to find modern ways of capturing ancient Provençal moods. Medieval art wasn’t realistic. Why should modern art be?

Thus Madame Cézanne in a Yellow Chair is a modern Madonna, a secular subject that has gone in search of old religious feelings. And the salt of the earth types he liked to paint, the workers on his farm, at the Jas de Bouffan mansion, are as saintly and stoic as the elongated figures clustered around the outside of Aix Cathedral.

The Tate show tries to present him as a more politically concerned artist than we generally assume, a social observer, a bemoaner of the fate of women, but this is just cross-your-fingers-and- hope scholarship. Just as his staunch Catholicism is overlooked, so too are his right-wing views and his antisemitic position on the Dreyfus Affair.

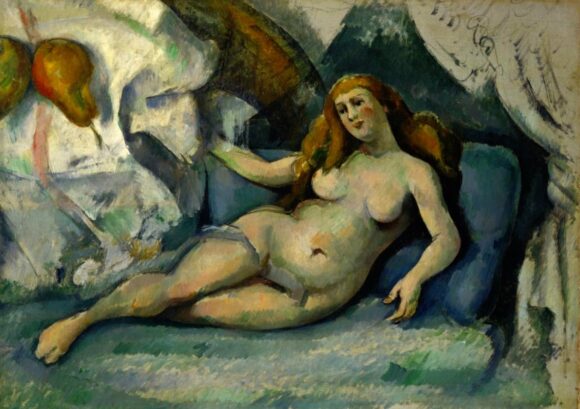

Early and violent pictures such as The Murder or The Eternal Feminine are clearly the works of a troubled misogynist. They take us to dark places in Cézanne’s attitude to women. An extraordinary painting known as Nude Woman (Leda?) shows an alluring prostitute displaying herself in her boudoir while giant portions of fruit — out of scale and fiercely symbolic — hover above her as evidence, surely, of her biblical origins in the garden of Eden.

Thus the curious, conflicted, eternally puzzling figure of Cézanne gives the creators of this event a right old run around. They never get near him. I suspect no one ever will.

Cézanne is at Tate Modern, London SE1, until March 12