It falls to few artists to be involved as fiercely with their times as William Kentridge was and is involved with his. Born in Johannesburg in 1955, he grew up in apartheid South Africa, where he witnessed not only the repression of the black community but also its resistance and triumph. And all the time, as a white observer who sided with the black cause, he was making prickly art about it.

The results have gone on show in an extraordinary retrospective that has opened at the Royal Academy (until Dec 11). It’s extraordinary for several reasons: because it tells the story of the black struggle so vividly; because it reveals Kentridge to be a brave witness; and because it is packed with so much art, in so many different formats.

Kentridge’s default talent is drawing. It is how he began in art and the wellspring of everything he did next. The result is a zebra of a show with a relentless black and white presence. The opening room, filled with accusatory depictions of Johannesburg in the 1980s, done with black charcoal, launches attack after attack on the privileged white folk of the city, lounging in the bars, despoiling the land, killing the rhinos.

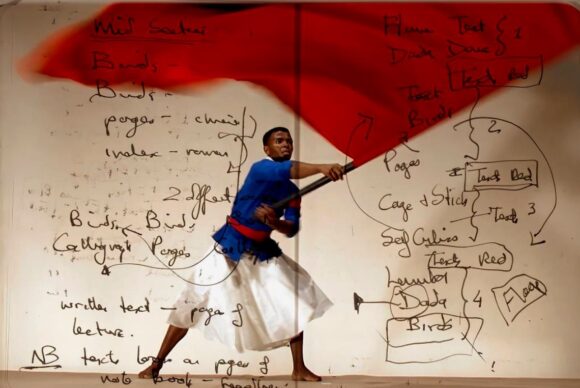

Artistically, though, the big story is how Kentridge’s drawing talent is expanded into a dizzying array of forms and media. I first encountered him through his homemade animations, which were created by drawing on the studio wall and filming the results with a movie camera as he continuously erased and redrew the image. The central gallery at the Royal Academy is filled with these dark homemade cartoons, morosely describing the horror of South Africa.

Having unleashed his accusatory drawing hand on the field of animation, Kentridge goes on to release it on pretty much every medium: sculpture, tapestry, film, word art, opera. Examples of restless formats jostle for space in a frantic occupation. There’s even a chilling puppet show playing on the hour in the hexagon.

As it nears its end the show tones down its anger and replaces it with a fascination with trees and gardens. Kentridge is growing old. But he has done his bit as a witness, and deserves this gentler retirement.