There’s an awkwardness to the big Lucian Freud exhibition that has arrived at the National Gallery. For a start, what is it doing at the National Gallery, occupying the same old master rooms occupied most recently by Raphael and before that by Titian? Freud (1922-2011) was a sizzling contemporary presence, no arguments there, but does he already deserve such a grand promotion to the ranks of Raphael and Titian?

Then there is the arrangement of the show itself. It’s broadly chronological, but every now and then stops being chronological and turns thematic, leaping across the decades to create stretches of temporal confusion.

These are big rooms too: Raphael-sized rooms. The work gathered here doesn’t quite fill them. Five or six important paintings that would have made it a more complete story are missing.

Finally, there is the exhibition title, Lucian Freud: New Perspectives. It’s excessively hopeful. What I see before me has nothing radically different to propose from the other Freud shows that have been such a popular feature on the exhibition circuit in recent years.

Here and there the curators huff and puff about wanting to avoid the usual biographical readings of Freud’s sexy and intimate art. And some of their captions twist themselves into knots trying to suggest that he treated paint like flesh and flesh like paint, especially in the harsh, riveting nudes that dominate the latter stages of the show. But none of that adds up to a new perspective.

Which is not to say there is nothing fascinating or thrilling to see here. There is. Plenty of it. Many of his best-known images have been mixed with some that have not been seen for decades. But instead of searching hopelessly for new perspectives, the best way to experience this event is the old way: picture by picture, sizzling moment by sizzling moment. Forget the curators. Follow the artist.

One of the reasons his journey is so interesting is because he was not a fluent or natural talent. No Raphael. No Titian. Freud was something edgier, angstier, more modern. At the centre of his effortful journey was a sense of struggle, a victory of determination over touch, milestoned by big changes in his painterly style.

The prime example is the dramatic turnaround that occurred in 1954 when he stopped painting the tight, stylised heads and top halves of his wives and lovers that characterise his first Freudian epoch and began working on the big, painterly, full-length nudes of all and sundry that characterise his next phase.

This struggle to find a style that fits is already evident in the show’s opening room, where the shaky chronology kicks off with a weird little self-portrait from 1940, fashioned from thick, scrambled brushstrokes, in which he gives himself a face so flat it looks as if it has been run over by a steamroller.

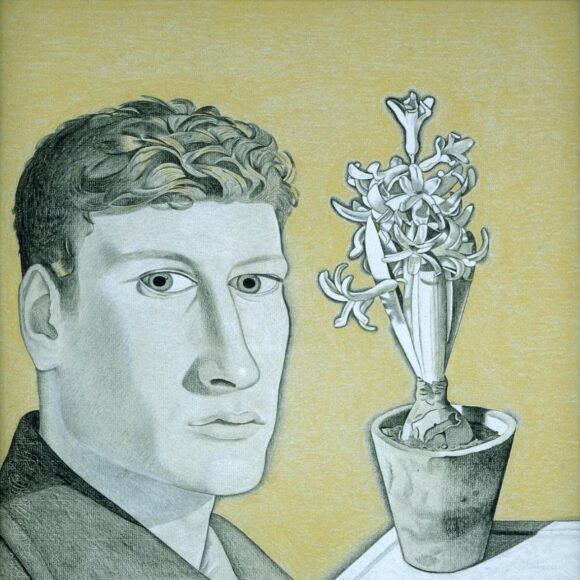

Five years later, his touch has become super-precise, and he turns to look at us with an accusatory stare, as if it is somehow our fault that he is now working with the smallest brush in the box.

This fierce appetite for self-portraiture needs surely to be understood in biographical and psychological terms — sorry, curators. Freud arrived in Britain in 1933, a Jew fleeing from Nazi Germany. You do not have to be his grandfather Sigmund to see the origin of his unsmiling insistence that we notice him in the violent uprooting that landed him on these shores. In British society he was always the one-off, the outsider.

One of the reasons his portrait of Queen Elizabeth II from 2001 — hanging here in splendid isolation in a space five sizes too large for it — is such a coarse and unconvincing likeness is because there is so little emotional connection between the artist and his subject. Having treated most of his sitters as lumps of glistening flesh, Freud is fundamentally ill equipped to deal with the warmer demands of painting a portrait of the Queen.

However, among the show’s more useful corrections is the observation that he could do warmth when the occasion demanded it. A thematic detour titled Portraying Intimacy shows him gazing down at his family and friends with tangible tenderness. You see it even more clearly in the earlier portraits of his wives, done in his first, precise style, notably in a gorgeous trilogy of lovey-dovey portrayals of his second wife, Caroline Blackwood.

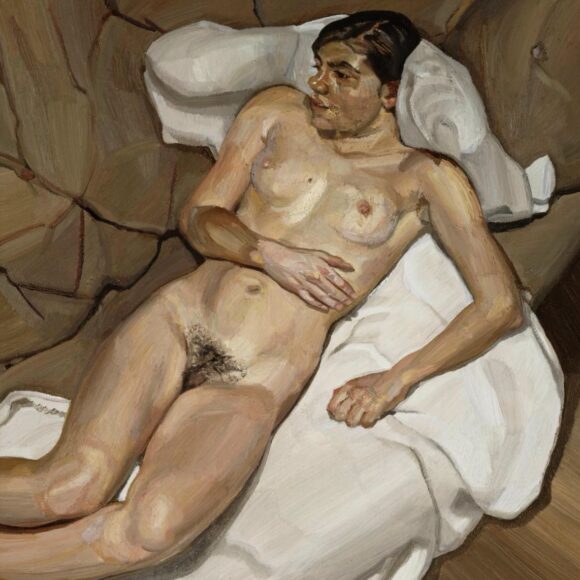

That said, his naked portrait of his daughter Bella, stretched out on a sofa, included here as an example of this newly discovered “intimacy”, is so strikingly direct and unwavering it cannot help but press the “creepy” button. Has there ever been a more skilled and accurate painter of the female pudendum than Lucian Freud? I think not. He certainly had a lot of practice.

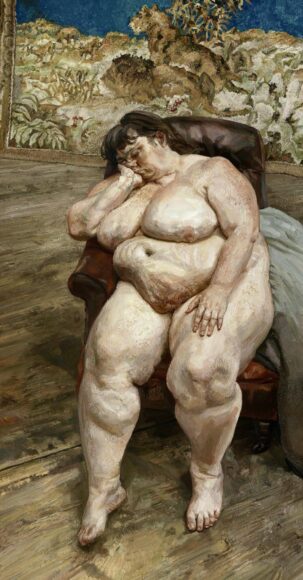

Having zigzagged through the first half of his career, the show finds itself on firmer ground when it reaches its final stretch and concludes with the big, looming, scary nudes that are such an unforgettable feature of his last style.

Spaces that had previously felt too large for him seem suddenly a bit cramped as they fill up with giant paintings of the massive Leigh Bowery, with his anaconda-sized dong, or the sprawling benefits supervisor Sue Tilley, whose huge rolls of naked fat are examined forensically as she dozes in a scruffy armchair.

Even here, in these exciting final moments, the curators manage to be awkward. The caption for the show’s last painting, a seated portrait of a middle-aged brigadier in his unbuttoned uniform, tells us that “even though the figure is completely dressed, it is perhaps the most ‘naked’ portrait depicted by Freud”.

Open your eyes, curators. Open your eyes.

Lucian Freud: New Perspectives is at the National Gallery, London WC2, until January 22