Topic of the month on the art front has been: forgotten women. Until now, it has raged chiefly on the books pages, where an assortment of feisty tomes on the subject have been receiving excited reviews.

Femina, by Janina Ramirez, is “writing women back into history” by listing and celebrating the undervalued heroines of the Middle Ages. The Story of Art Without Men, by Katy Hessel, gives us a pantheon of women artists whose work has been ignored in previous masculinist histories. Phaidon’s Great Women Painters, on the way in October, will leave no female reputation undiscovered as it trawls the annals for omissions. Fair to say, I think, that forgotten women are being enthusiastically remembered.

However, reading about the achievements of omitted art heroines must always be a second-hand experience. What we really need to do is see their work. So the blogger and curator Katy Hessel should be applauded for simultaneously bombarding us with relentless announcements about her book while mounting an elegant survey of some of the artists she applauds in her man-less story.

The show, loosely based on the book’s final chapter, sports the dance-along title of The Story of Art as it’s Still Being Written. What we are being presented with here is not omitted Renaissance heroines from Bologna, but a circle of active female artists in whose work Hessel is particularly interested.

One of the best things about her book is the untrammelled enthusiasm she brings to the task of unearthing numerous female histories. There’s none of the ponderous doominess in her writing that marks the efforts of her predecessors in the field: no dour showering of gender-based guilt. This sense of genuinely loving the work she is writing about transfers tellingly to the show. It’s a celebration not an accusation.

Fifteen women artists, all active today, with the exception of the tragic Khadija Saye, who died in the Grenfell fire, have been given space to express themselves in a roomy layout that allows each to be independently admired.

The first work you see, because it’s unmissable, is Chantal Joffe’s 10ft tall portrait of her teenage daughter in a striking red prom dress. This scale of portraiture is usually reserved for costly swagger likenesses of the rich and noble. By devoting the looming size to a nervous portrait of her daughter setting off on her big night, Joffe turns the personal into the public and makes something universal out of an intimate moment.

Tracey Emin gives us a trademark sprawling nude, her head obliterated in a Tom and Jerry tussle of thrashing red brush strokes, while the picture’s title — Rip my heart out You F***ing C*** — proves that her recent cancer has not robbed Emin of any of her accusatory anger.

All the artists here are exploring the fertile divide that separates the figurative from the abstract. Some lean one way, some the other, but all bring something particular to the party. In most group shows the artists are bunched together in curatorial clusters that blur their individuality.

Not here. Black artists are notably well represented, with Amy Sherald, Zanele Muholi, Somaya Critchlow and Deborah Roberts all making tasty appearances. Something about the tone of today’s black women’s art, with its emphasis on emerging identities and personal stories, chimes not only with Hessel’s tastes, but also with the general direction in which art is heading.

This, then, is a story full of stories. And the one that gripped me most forcefully was told in a self-portrait by Celia Paul titled Overshadowed. Paul used to be the lover of Lucian Freud. She met him when she was a student and he was her teacher. So the relationship never reached any kind of equilibrium. In Overshadowed, Paul shows herself sitting dutifully in a chair, staring straight at us with an uncomfortable face, while a large, dark shadow falls on her and seems almost to enclose her. I wonder who that is?

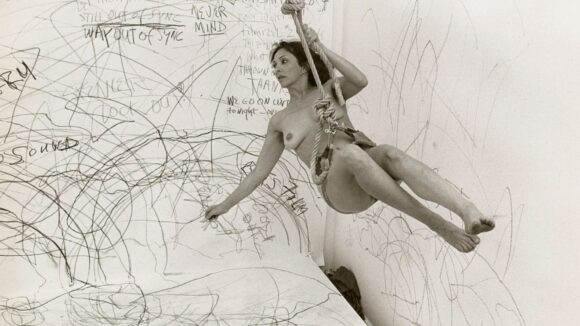

At the Barbican Art Gallery an ambitious survey is attempting to solidify and enlarge the reputation of the American performance artist Carolee Schneemann (1939-2019). I wouldn’t call her a forgotten artist — we’ve all heard of Schneemann, usually for the wrong reasons — but she is certainly underexplored and probably undervalued.

The reason we have heard of her is because in the 1960s and 1970s she seemed never to miss an opportunity to take off her clothes and make “body art”. To the casual viewer, her performances were only mildly distinguishable from full-on orgies. When it came to recurring nakedness, no one in modern aesthetics could hold a candle to Schneemann.

The Barbican show successfully removes most of the heat and sweatiness from our image of Schneemann by forensically examining all of her important performances in calm documentary detail and by adding thoughtful ruminations here and there upon the reasons for her nakedness. Schneemann saw her body as an artistic tool to be wielded in a battle with masculinist art history. Her feminist critics, though, were quick to accuse her of self-evident narcissism. Hmmm.

I left the show admiring the early paintings she made as an abstract expressionist, and grateful to the Barbican for enlarging her career. When it came to the nudity, however, an insistent question continued to trouble me: would Schneemann have been as keen to make body art if she didn’t have the figure of a supermodel and the looks of a Hollywood starlet?

The Story of Art as it’s Still Being Written, at the Victoria Miro Gallery, London N1, until October 1; Carolee Schneemann, at the Barbican Art Gallery, London EC2, until January 8