I was thinking the other day about an art book I want to write. Its title would be: Art — How It All Turned to Shit. Every word in the book would be true. Playing a central role in the tragedy would be Damien Hirst.

Among art critics working today, I do not believe Hirst has a more loyal admirer than me. I have followed his artistic progress ever since he photographed himself as a teenager in a mortuary smiling next to a corpse. I’ve interviewed him frequently, heaped praise on him and defended him stoutly when he went too far. I’ve done all this because — and this really marks me out — I believe in him. Fundamentally I believe he has inside him what only true artists have inside them.

But because I have been with him every step of the way, I also know how it all went wrong, and why. It’s a telling story. It says a lot about him, yes, but it says a lot more about the jealous, small-minded, play-acting entity that is the contemporary art world. If I could put a stake through its heart, I would.

In a couple of weeks, to coincide with the opening of the Frieze art fair, we are going to witness Hirst’s latest art gimmick. In an effort to promote his NFTs, he is burning thousands of his pictures, valued at about £10 million. The television cameras and headline writers will be there. My faith in him will receive another clout.

If you don’t know what NFTs are, you’re lucky. Non-fungible tokens were invented by the Devil to lure fools into the art world and persuade them to spend their money on nothing. More on them in a moment. First I think we should remember how we got here because it is instructive. So let me wipe away a tear and recall the good days of Damien Hirst — the artist who changed everything.

The art world today is a completely different creature from the art world of four decades ago, when Hirst began his cursed journey. Today millions flock to Tate Modern. The Turner prize is a must-opine event. The prices for modern art have reached cosmic levels. But all this is new. Only recently has Britain learnt to adore contemporary art. For most of the 20th century it hated it, mocked it, avoided it, considered it worthless. Until Hirst arrived.

In the 1980s, before he exploded into our consciousness, art was a minority interest enjoyed by a modest number of monkish cult members. If you put up a sign outside a gallery saying “Contemporary art this way”, the queue would have stretched in the opposite direction.

As a fledgling art critic starting out on the road to today, I remember the ceaseless moaning that could still be heard about the “Tate bricks” affair, the purchase of Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII by the Tate Gallery in 1972 for £2,297. Even ten years later, the thought of wasting “all that taxpayer’s money” on “a pile of bricks” was still driving people apoplectic. Enter Hirst.

In 1988 he gathered together a gang of classmates from Goldsmiths, took over a warehouse in Docklands and unleashed himself and a fresh artistic spirit in a show he called Freeze. Wild, varied, energetic and rabidly contemporary, Freeze was a handful of smelling salts shoved up the nose of the traditional British art world. Suddenly everybody woke up.

The movement launched by the show — the Young British Artists — wasn’t really a movement. It was more of an attitude, a punkish disregard for the past allied to a noisy creative energy that never settled into a habit. The YBAs made paintings, sculptures, films, photos, installations — whatever it took. They were young, they were free, kept their teeth nice and clean.

At their centre, Hirst began rolling out a succession of the most inventive and impactful art works I had seen. At the Venice Biennale of 1993 he exhibited Mother and Child (Divided), a full-size cow and her calf cut in half and suspended in formaldehyde inside four looming glass boxes. It was the first time I had walked through the middle of a cow. I can still remember the excitement today.

Before that there was, of course, the shark, a real-life monster of the seas floating silently and immovably in the Saatchi Gallery, giving you Jaws-style goose bumps. And before the shark there was the scary flies piece, in which an endless stream of flies hatched in a rotting cow’s head were electrocuted by a neon zapper.

The ideas in which he was rubbing our noses with these dramatic artworks — death, mortality, sex, religion — had an old master bigness to them, but the way they were being explored could not have felt more new. Auschwitz moods. Minimalist set-ups. In my book Hirst did enough in his first five years of action to warrant a permanent seat in the pantheon of great British artists. Unfortunately it was also about now that the problems started.

Britain finally had an artist, and an art movement, of whom the whole world was taking notice. Modern art had long-jumped from page 27 in the newspapers to page 1. But instead of celebrating this surge in interest, the monks of the British art world seemed to find it internationally embarrassing.

People always imagine that the art establishment was immensely supportive of Hirst. That it helped to make him. Gave him shows. Bought his work. It didn’t. When I was head of arts at Channel 4 and put the Turner prize on television I was made continuously aware of how little keenness there was for him in the upper echelons. He was too flashy, they said. Too noisy. He lacked the art world’s favourite quality: “rigour”. They wanted grey graphs worked out with a ruler. He was giving them pickled sheep.

The process of not welcoming him, not buying him, not appreciating him, pushed him ever further away from the art establishment and ever deeper into the commercial art world. To make it all worse, he was wilful and cussed by nature. He turned down gongs and a knighthood. He turned down offers to show at the Venice Biennale. He refused to join the Royal Academy. The cosy relationship that other artists of his heft enjoyed with the establishment was simply not for him. They saw him as Jack the Lad. He saw himself as Dick Turpin.

Having single-handedly sparked a new national interest in contemporary art — an interest that led directly to the opening of Tate Modern in 2000 — but with zero affection being directed at him by the art establishment, Hirst decided to throw in his lot with Mammon and play games with rich people instead: to milk the system for all it was worth. By 2009 he’d accumulated a fortune estimated at £235 million by The Sunday Times Rich List. And was slithering to the bottom in a slow artistic decline.

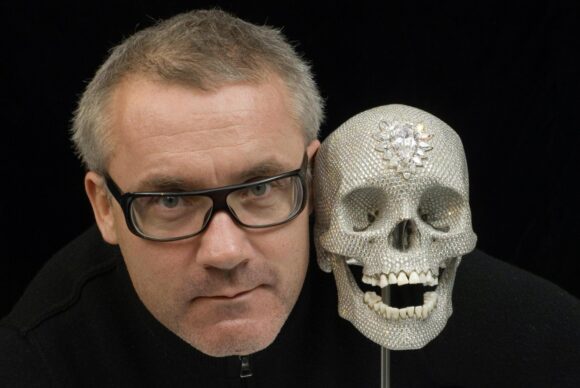

It was slow because he was too real an artist, too full of ideas, to turn bad overnight. For the past 20 or so years he has usually managed to throw something worthwhile into the expensive dross. The diamond skull he tried to sell in 2007 for £50 million was a piece of money-crazed kitsch, but boy did it pack a visual punch.

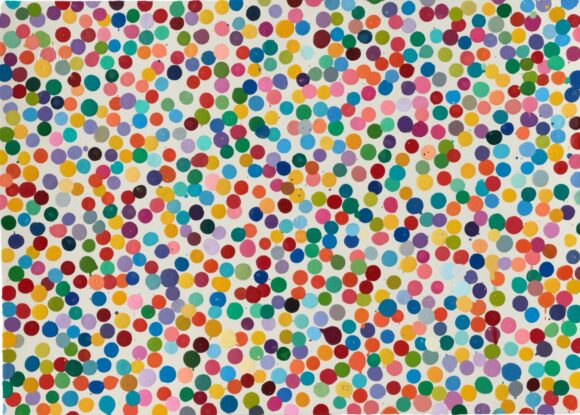

One of his more reliable talents is as an instinctive designer with an eye for colour. Having realised early on that all people really want is something nice to hang on the wall, he has kept up a seemingly endless flow of dot pictures.

I used to own one of the early ones, bought for a couple of grand, a minimalist arrangement of dots in a fetching triangle. Hand on heart, it was lovely to contemplate and gave me more pleasure than anything else on my walls. Alas, having realised that people love dots, Hirst has set about saturating the market. Which brings me to the NFTs he is going to burn in Frieze week.

Non-fungible tokens are a grotesque invention of the Covid era when people spent too much time in front of their computers, losing their grasp of reality. When you buy an NFT you buy ownership of something — but not the thing itself. It’s like walking into a shop and buying the words “a pint of milk” rather than an actual pint of milk. You own the ownership. But nothing else.

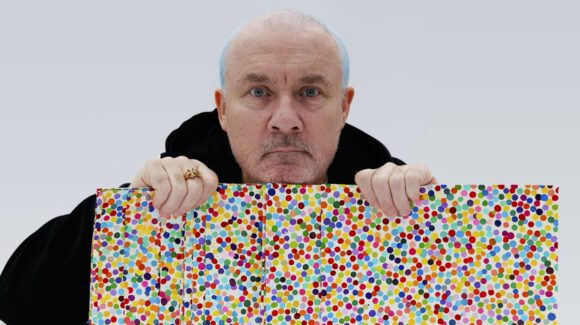

Hirst’s first NFT collection, called The Currency, consists of 10,000 dot paintings made with enamel paint on handmade paper. Where my dots were carefully separated, these new ones are crowded together in boisterous jumbles. Each sheet has a hologram of the artist on it as well as a stamp and signature.

A year ago he announced that he was putting all 10,000 dot pictures up for sale on the internet at $2,000 a pop, and that the buyers would have the choice of owning the physical artwork or the NFT. He sold the lot — 5,149 decided to keep the artwork, 4,851 thought they would rather have the NFT. Those are the ones whose dot paintings he is burning — 4,851 victims of the NFT craze.

I began this moan by insisting that I believe in Damien Hirst as an artist and consider myself to be one of his staunchest defenders. So allow me a moment’s hesitation while I consider the possibility that what he is actually doing here is testing the boundary between the real and the unreal, and using NFTs to launch a philosophical investigation of the nature of art.

OK, I’ve considered it. It’s clearly balls. Dick Turpin rides again.

The Currency, Newport Street Gallery, London SE11, from Thu to Oct 30