Winslow Homer and Michelangelo are two artists I never imagined I would pair in the same sentence, but a compelling show that has opened at the National Gallery has forced my hand. On the surface, they have zero in common. One was a universally acclaimed genius of the Renaissance, the other a 19th-century boat painter of whom few have heard outside his native US. But beneath the surface, where it counts in art, they shared a vital quality.

There is no English word for it. So I will have to use the Italian: terribilità. It means something like: “inducing terror”. Michelangelo’s contemporaries recognised it when they looked up at the Sistine ceiling and saw an angry God staring down at them. What have wedone? Why us? Homer, who produced no obvious religious art, found it in nature, and especially in the huge, swelling, tumultuous seas of the North Atlantic. Terribilità makes you feel small, vulnerable, guilty. Any artist who has it in their quiver has a powerful arrow to let fly.

Like a surprising number of notable American artists, Homer (1836-1910) started out as a commercial illustrator, working in Boston for popular magazines such as Harper’s Weekly. He had a talent for storytelling; knew how to trigger interest and keep you guessing. The National Gallery tribute doesn’t go into any of this — his beginnings don’t feature — but the first paintings we see, produced after Harper’ssent him south to cover the American Civil War, make it quickly obvious.

The Veteran in a New Field, from 1865, is a back view of a ragged farmer swinging a scythe at a looming cliff of yellow corn. “That’s a whole heap of scything you got in front of you, son.” Then you notice the Confederate jacket he has thrown off to do the work. And the painting jumps into life as a symbolic mystery. “Son, what kind of scything are we talking about here . . . ?”

For we Limeys who know so little about Homer’s art because there’s so little of it to be seen here (no significant painting in any national collection), the sense of lurking symbolism that lifts these narratives on to a higher plane feels new. Our Victorian art was just as keen to find moments of drama in everyday life, but it did so more fussily and with none of the biblical cadences that Homer brings to the task.

The Fog Warning, from 1885, the first of his famous sea paintings in the show, is Moby-Dick in a gold frame. A lonely rower caught on a choppy sea as the fog falls — his boat lifted to a perilous vertical by the waves — stares across at the sails of a far-away schooner gliding along the horizon. It’s safe. He isn’t. And my, what a lot of ocean there is between them.

The biggest issue of the American Civil War, slavery, keeps popping up as a concern in Homer’s postwar art, but his determination to keep the meanings open makes his position hard to read. A Visit From the Old Mistress, of 1876, shows three “freed” female slaves crowded into a dark hut, being visited by the starchy widow in a black dress who used to own them.

They live in squalor. She obviously does not. They have children dangling from them. She has an ornate fan. Two worlds are colliding and a note of terribilità is being struck. But it’s the collision of opposites that interests the painter, not the apportioning of blame. The captions tie themselves into tangles trying to project modern thinking on to the subject, but the painting remains stubbornly ambiguous.

Telling it like it is by not telling it like it is is a strategy only the better artists dare to employ. This involving show, which has obviously set out to enlarge Homer’s transatlantic reputation, gives us a painter who is more progressive than we might have suspected. It isn’t just the tricky conceptualism that lifts his scenes of everyday American life above the Victorian norm. There’s an unpredictability also to his interests, a difference to the things he notices.

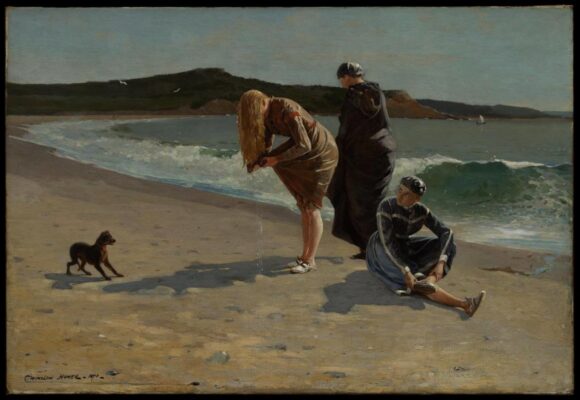

A girl on a beach wrings out her hair on the sand after an ocean swim while her dog barks at her. A boy climbs up a sand dune and puts his hand into a burrow dug by sand martins while the birds buzz around him in panic. The textures feel different because they are American: everyday scenes of a different everyday.

It’s obvious, too, that he has been looking at progressive French art — at Géricault, at Courbet, maybe even at Manet. Where our own Victorian art dismissed these French influences as the Devil’s work, the fresh and open-minded American welcomed them. You see it in the clearness of Homer’s colours: the emerald green of his seas, the golden yellow of his corn.

But the terribilità, when it starts to stir in his work, has nothing French about it. Homer travelled enthusiastically, to Barbados, Cuba, France, England. He made art wherever he went. But one of his feet seemed always to be anchored in the crease of the Bible Belt.

The great suite of sea paintings in which the show culminates keep setting the tiny figure of man against the mighty power of nature. In huge, thrillingly wild seas, tiny boats bob and sway, as the precariousness of human existence is measured against the vastness of the ocean.

We’re watching the birth of an unmistakably independent American art. The biblical tone it keeps striking is what makes it so distinctive.

Winslow Homer: Force of Nature, at the National Gallery, London WC2, until Jan 8