One of the best things about being the Queen is the access it grants you to the royal jewel box. Imagine being able to run your fingers through all that fabulous Windsor bling and trying to decide: will it be the emeralds tonight or the rubies?

Over the centuries the British monarchy has amassed a superior collection of bling to unleash on state occasions and official evenings out. A perfect selection of these intoxicating royal baubles — crowns, tiaras, necklaces, brooches — has gone on show at Buckingham Palace, where they may need to employ a special footman to mop up the drool. Some of the biggest blobs will be mine.

The story of bling goes back a lot deeper, of course, than the history of the Windsors. Humans have been in love with jewellery since they first strode out of Africa. The Cro-Magnons wore necklaces made of teeth, bone and stones, stitched on to animal sinews. Kings, queens, pharaohs, khans and emperors were buried with their jewels to smooth their passage through the afterlife. Bling has always had a magic or talismanic power. Which is presumably why I only just made it round this show without falling over.

There are many reasons to visit the event they have clunkily entitled Platinum Jubilee: The Queen’s Accession. (It just doesn’t roll off the tongue!) You get to stroll through the royal apartments. You see some superb 18th-century fireplaces. You pass by some of Winterhalter’s busiest paintings of Victoria and Albert. But the best reason for going is to feel the lightning bolts emanating from the Delhi Durbar necklace, worn by Queen Mary at the final Indian durbar in 1911. Or to sense the excitement visited on the eyes by the Girls of Great Britain and Ireland tiara, commissioned from Garrard & Co, the royal jewellers, in 1893 as a national thank you to the monarchy. Great bling has great power. It speaks to the nerve ends and makes you dizzy. And my, what a lot of it there is here.

The show looks back at the Queen’s story from her precocious appearance as a 12-year-old princess at her father’s coronation in 1937 to her most recent attendance at the Platinum Jubilee. However, don’t for one moment think this is another run-of-the-mill summary of her reign. Two smart curatorial decisions lift this event high above the general platinum standard and turn it into something riveting.

The first is the focus on those scintillating royal jewels. Beautifully lit, beautifully presented, the bling on display here will send arrows of desire thundering into the heart of every sentient visitor. The other clever decision is to confine most of the royal photography to Dorothy Wilding. This is as much a revelatory Wilding exhibition as it is a platinum celebration.

Wilding is a ubiquitous presence in our lives, yet enormously underrated. She was the photographer brought in to record the key early moments of Her Majesty’s reign. She photographed George VI’s coronation and captured Elizabeth in a cream robe edged with gold and a lovely coronet fashioned by Garrard. When Elizabeth was 20 Wilding took her formal portrait, in which the princess wears a double string of pearls given to her on her 18th birthday. Pearls became her thing and she wore them again a year later when she was engaged to Prince Philip.

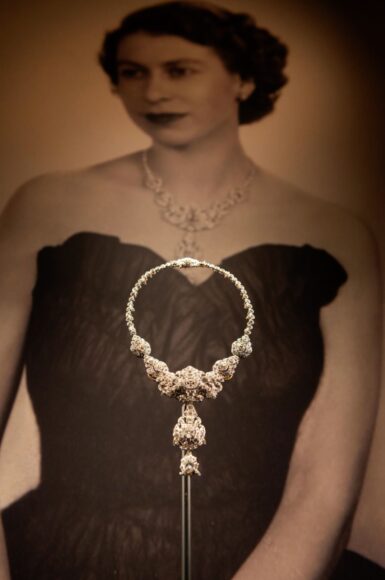

This is how the show works. You get the fabulous Wilding photograph. And in front of it you get the actual jewels the Queen is wearing in the picture. The photos are black-and-white with that shadowy deepness that is unique to vintage silver gelatin prints. The jewels before them burst into sparkling colour.

In 1952, straight after the royal accession, Wilding was commissioned to produce the official photographs that would serve as the model for the new queen’s appearance on our stamps and coinage. It was a portentous photographic duty. And in an inspired piece of show-making, the exhibition organisers have included the trial photographs that Wilding took as well as the chosen versions. So we can see her making subtle shifts and improvements as she searches for a postal perfection.

It turns out that, earlier in her career, Wilding had studied retouching, and if you lean into her gorgeous silver platinum variations on the Queen’s profile you can see little ink marks around the eyes and lips in which the photogenic queen is having her looks made more clear cut.

In the first set of profile pictures Wilding took, Her Majesty has nothing on her head, and could have been any old beautiful English country gal. So Wilding was recommissioned to picture the Queen in the Diamond Diadem, originally made for George IV’s coronation in 1820, featuring the national symbols of Ireland, Scotland and England. That did the trick. We also learn that the Queen faces right on our coins because her father faced left, and an unwritten royal protocol demands that successive monarchs swap sides.

Another surprise is the inclusion of Wilding shoots that came to nothing. Never seen in an official capacity, they are charmingly fresh and engrossing. I couldn’t help but notice that several of the unseen shots of the Queen feature her smiling broadly. Someone seems to have decided that we don’t need a beaming queen.

The photography, then, is revelatory, a much needed reappreciation of the unfairly forgotten Wilding. More of her work please.

In bling terms, the stand-out moment arrives when we reach the vitrine containing the Delhi Durbar necklace, a piece of bejewelled magic fashioned by Garrard out of assorted gems already in the royal collection. A ring of big emeralds alternates with a ring of diamonds; at the front a pear-shaped emerald hangs next to the Cullinan VII, one of the stones cut from the largest diamond yet found, the 3,106-carat Cullinan Diamond.

Your Majesty, I beg you. Please wear this sublime bauble more often.

Platinum Jubilee: The Queen’s Accession, at Buckingham Palace, London SW1, until Oct 2