Few words strike fear in the heart of the honest art lover as immediately or as fiercely as that terrifying etymological diptych “immersive experience”. Invented by the Devil to sow doubt in the populace about what is worthwhile and what is not, these American horrors are springing up like postwar buddleia in empty warehouses and forsaken industrial units around the land.

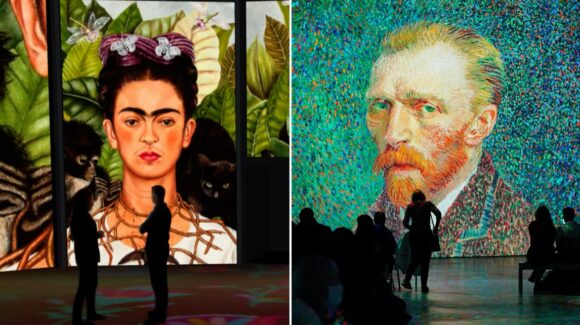

What is an “immersive experience”? Basically, it’s an art event without any art in it, created with computers and speakers. What used to be called a son et lumière (or a sound and light show) in the old days of tourism. Today, they are usually about famous painters and involve sitting in a dark hangar surrounded by noisy projections.

But fear not, honest art lover. Driven by a thirst for knowledge, your intrepid scribe has road-tested some of them for you. It’s what art critics do. They suffer, so others need not.

My first stop was Mexican Geniuses, which has opened deep in the “rejuvenated” Heseltinian Docklands of east London, at Canada Water. The geniuses in question are the painters Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, whose tremulous story is being told in a low, flat metal box that sits sulkily next to a branch of Decathlon beside a dank urban pond bobbing with beer cans.

I arrived before opening and was first in the queue. A line of angsty grey swans swam backwards and forwards across Canada Water, dodging the cans and wondering how it had come to this. While I stared at a small metal door with “Mexican Geniuses” written above it, wondering if this really was the entrance. It was.

Immersive experiences don’t exist until someone turns on the electricity. Their natural state is a black vacuum in which nothing happens. Then someone throws a switch and the whole caboodle springs to life. The music starts. The lights jump on. The metal door swings open. Smiles pop up loudly on the faces of the door staff. In the blink of an eye, nothingness has become somethingness.

Why Kahlo and Rivera? Both are riveting artists, no argument there, but the Docklands of London are a long way from Mexico. And even though Kahlo has become the premier face of artistic feminism there is no way her presence can feel anything but effortfully imported next to the Decathlon on Canada Water.

Immersive Frida Kahlo has already been playing in Toronto, Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Houston, Denver and Los Angeles. And having polka-dotted America, the electronic Kahlo has teamed up with a circuit board Rivera to invade other continents.

Tellingly, Kahlo died in 1954. So her work has only two years left in copyright. The sanctioned Kahlo events that have flooded the art world recently may have nothing to do with the fact that soon anybody, anywhere, will be able to do anything they wish with the images of Kahlo and Rivera, who died quickly after her in 1957, but it is a handy coincidence. In the words of the Abba holograms chirping away at us in Abba Voyage, money, money, money is always sunny in the rich man’s world.

What do you get for your reduced £19.90 entrance fee? First off, it’s music, an unstoppable stream of mariachi melodies that follow you round as you search for an opening in the curtains. “Ay, ay, ay, ay, canta y no llores,” the questing visitor is advised: sing and don’t cry. Easier said than done.

An opening biographical section, enlivened with lifesize papier-mâché “Judas” dolls and authentic reproductions of paraphernalia from the couple’s house, tells their story at a decent depth. How she loved him. How he flirted. How they were both determined communists. It’s by far the most useful section. The same cannot be said of the son et lumière that follows.

Stepping into a noisy twilight, where rousing music rings unceasingly around you — imagine being stuck in a lift with Kate Bush who won’t stop singing Wuthering Heights — you lie down on one of the beanbags scattered like dog turds and await the digital arrival of the stars.

Rivera pops up first, a computerised Munchkin in Mexican black who tells of his love for Kahlo in an accent borrowed from a spaghetti western. Then she pops up on the other side of the hangar and reciprocates — before elbowing him aside and taking over. Only in name is Mexican Geniuses about Rivera and Kahlo. In reality — or rather in what passes for reality in this dodgily focused, continuously twitching cartoon-opera — it’s 85 per cent about Kahlo, with morsels of Rivera thrown in.

Why do people like these things? Conspicuously the creation of unseen strangers — the animator, set designer, scriptwriter, composer, corporation with the bank roll — immersive experiences have so little to do with their subjects. They are just gassy examples of artistic sci-fi invented by fantasists. And they are so wonky! If you must turn a small painting into a wall-sized example of monster art, at least get it in focus.

Reader, I fled. It was all so ghastly. Having read some positive reactions to Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience, which has been “wowing visitors” in a trendier corner of London, I hot-footed over to Shoreditch expecting an improvement. Foolish me. It was worse.

The reproductions of the paintings were even less in focus. The son et lumière was even more tremulously pointless. And the storylines peddled in the surrounding info-niches even less reliable, notably the sudden claim, announced in a film, that Van Gogh was colour blind! This ludicrous suggestion, presented as a recently discovered fact, will leave hundreds of bemused visitors believing yet more porkies about poor old Vincent.

But wait, I hear the voice of reason whispering. Aren’t “immersive experiences” a welcoming porch through which the unanointed can enter? Is it not a good thing that those who might otherwise be uninterested in art are introduced to the subject? Won’t the kiddies humping the beanbags grow up to be art lovers like you?

Maybe. But probably not. And if they do, they’ll be disappointed. They’ll find that art doesn’t usually come with throbbing music and thunderous storylines. It isn’t best seen lying on your back with your legs in the air. It won’t generally be 50ft high or shudder into movement when the animation starts.

Frida’s paintings don’t move or sing or burst into stars at the thought of Diego. They are usually tiny, and just hang there, being great art. For some of us, the cultural saddoes, that’s enough.

Mexican Geniuses, at Dock X, Unit 1 Canada Water, London SE16. Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience, at 106 Commercial Street, London E1