Art can be impressive in many ways. It can be beautiful, emotional, atmospheric, it can deal fascinatingly with nature, with identity, with religion, and be full of big ideas. But where it has the power to disable you — leave you swaying with your tongue lolling out — is when it is technically brilliant. When the skills of the artist are so spectacularly evident they make you dizzy, art moves into the realm of magic. That’s how it is with Albrecht Dürer.

We’re talking about the first and ultimate artistic skill: mark making. Starting with a blank sheet, the artist has to find a way of transforming the complex three-dimensional world we have before us into a convincing arrangement of descriptive lines and signs. Today, we take those sorts of skills for granted. The camera has made them seem banal and unnecessary.

Occasionally, though, they can still force themselves into the foreground and astound you. Which is what happens in Dürer: The Making of a Renaissance Master at the Barber Institute in Birmingham.

The show has been put together by eight students on the curating course at the University of Birmingham. These eight students — eight lucky beasts! — have had the immense good fortune to be charged with assembling a Dürer exhibition from the works available in the royal collection — the Queen’s personal stash. They have risen to the task impressively. Their curating careers lie mostly ahead of them, but they will be hard pressed to improve on this perfect little opening blast.

It’s a tiny event. Three drawings. One painting. Sixteen prints. And a book. A guinea of exhibits, spread gently around a quiet alcove in the treasure-filled Barber Institute. With Dürer, it’s all about pressing your nose to the art and seeing what his marks are up to. And you can do that here in conditions of genuine intimacy. Art lovers, go to Birmingham.

The Queen’s collection is packed with Dürers because in the 1800s Victoria’s Albert hoovered up all the examples he could of Germany’s greatest artist. So the eight students had a lot to choose from. Their selection dwells initially on the different techniques employed by the master of Nuremberg. Woodcuts, engravings and etchings can seem like interchangeable methods of making a print. But they are fiercely different. Each carries its own creative baggage.

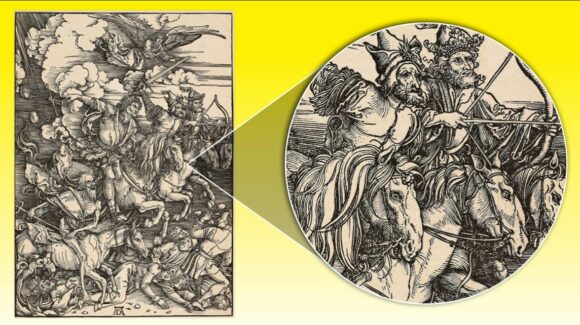

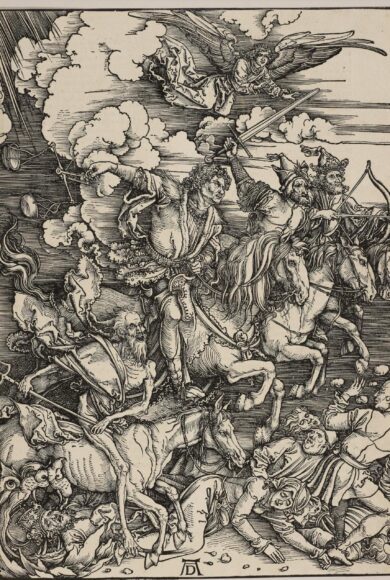

We start with Dürer’s first forte: woodcuts. His great print The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse shows four wild-eyed jockeys, representing death, famine, war and plague, rampaging across Earth on the final day. Dürer carved it in 1498 when — as the captions helpfully illuminate — the end of the world really was nigh. The year 1500 was universally expected to be humanity’s final one. And boy, do you feel it here.

It’s like watching the Grand National from a dangerous vantage point under Becher’s Brook. The astonishing action print seems to be happening above you, filling the gallery with the mad neighing of horses and the terrifying thunder of hoofs. There’s something about woodcuts that gives the image an emotional starkness: a sense of not messing about. Dürer’s Apocalypse makes the end of the world feel vividly present. One look at it in 1498 and I would have been straight to the confessional, begging for forgiveness.

The woodcuts are mightily impressive. You wonder how this squiggle becomes a cloud and that one becomes a hoof. Then you move on to his engravings, and the lid on the talent tub gets blown off. It’s astonishing what the process of scratching little lines into a copper plate can achieve in the hands of a genius. Dürer was the greatest engraver because he manages to convey football fields of information with marks no bigger than a hyphen.

Look at the print of St Jerome in his Study and see how the sun flooding through the thick bottle-glass window is leaving scattered bottle-glass reflections on the wall. It’s a piece of observation worthy of a great impressionist, yet here is Dürer in 1514 throwing it in as an incidental detail. Or see how the shadows on Jerome’s desk are perfectly conveyed with tiny diminutions of dots. It’s breathtaking.

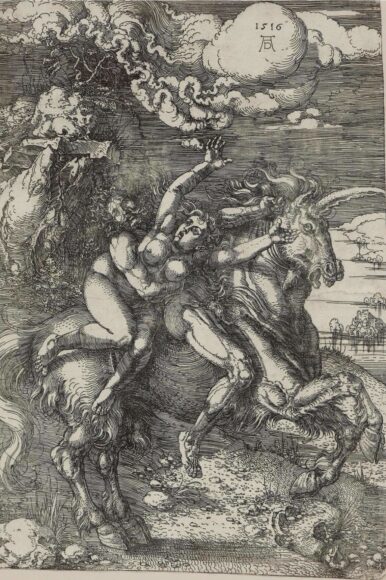

His least successful printing method was etching, a complex process involving acid and wax that seemed to distance him from the mark-making. The single example here, A Woman Abducted by a Man on a Unicorn, is a dark and troubling image with plenty of Dürer’s trademark sturm und drang in its mood, but the figures are having trouble separating themselves from the background and the marks are not as precisely descriptive as usual.

Apologies. In my paean to Dürer’s technical brilliance I am short-changing the student curators responsible for this lovely gallery moment by not giving you a bigger picture of their thoughtful show.

Having introduced the topic of printing technique, they, unlike me, move purposefully forward to two more themes. One deals with Dürer’s circle of friends and patrons, who helped to enlarge his reputation and spread his work. So we are treated to a huddle of vivid portraits in the middle of which sits the show’s only oil painting: a miraculously lifelike likeness of Burkhard of Speyer. The third theme is billed as Captivating the Public. Dürer certainly knew how to do that. His prints set out deliberately to move and entertain. He could do erotic. He could do sentimental. He could do funny. He could do frightening. And this perfect little event has it all.

Dürer: The Making of a Renaissance Master, at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham, until Sep 25