Spare a thought for the art student. Covid has had a fierce impact on every type of educational journey — it’s the gift that keeps taking — but its impact on the art student has been especially harsh. Particularly when it comes to the biggest of all student moments: graduation.

Young birds get kicked out of the nest; students have graduation ceremonies. They put on fancy togs. They pick up their certificates. They have their photos done. Their parents come. Nothing signposts the transition from dependence to independence as legibly as the big day.

When Covid took away two years of evident graduation from the ranks of our emerging mathematicians, geographers, lawyers, historians and biologists, it put a sad hole in the photo albums ofcountless young lives. But the student that Covid hurt the most was the art student.

For art students, graduation, and the exhibition of your work that accompanies it, is not just an emergence. It’s the only chance. In other disciplines you can prove your worth with certificates and exam results. Not with art. Art needs to be looked at. Degree shows are pop-up events that usher in your future. Which is why my heart goes out to every single art student who had that opportunity snatched from them by the plague.

It’s also why I have just broken my daily step count record touring the output of this year’s cohorts from the Royal College of Art. The paperwork for the event blares: “Featuring work by over 900 students.” I reckon that’s an underestimate. (Art teachers are as bad at maths as their pupils.) Heavens, but there are a lot of people graduating this year from the Royal College of Art. And what terrible things they have had to deal with.

Two years of isolation. Two years of Old Testament plague. Two years of shortage of materials. Two years of chatting to themselves when they ought to have been chatting to the girl in the next studio, the one who came from Greece and had a thirst for knowledge, who studied sculpture at St Martin’s College before completing her MA at the RCA. Now, finally, they have their moment.

Going round degree shows is one of art’s big annual pleasures. It’s free. It’s fascinating. It’s fun. However, it’s a pleasure tinged with sadness. Underpinning every degree show is the horrible certainty that 99 per cent of the exhibitors will never be heard from again. Like the life cycle of a beautiful butterfly that flutters for a fortnight in the sun, lays its eggs and says goodbye, this is it for most art students. Only very rarely do you see work that blows you away and makes you think: “This is the next Paula Rego.”

What you find instead is valuable information about what’s going on in art. Art students are sponges. It’s the central paradox of their vocation. The reason so few of them go on to become successful artists is that they are so good at absorbing contemporary art fashions, and so bad at not absorbing them. Art students carry the past into the future. Where nobody wants it.

My journey round the RCA took me through the departments of painting, sculpture, photography, ceramics, jewellery and that especially au courant department that calls itself contemporary art practice, or CAP. I didn’t make it to architecture, design or engineering: my steps app would have exploded. But in the buzz and fuzz created by the hundreds of students I was able to appraise, the hazy outlines of three tendencies became visible.

The most obvious was the blurring of categories. At the RCA, painters sculpt and sculptors paint. Hardly anyone is specifically anything. In the photography department, the most exciting exhibit was a set of relief sculptures by Ariel Hacohen that looked like updated versions of the Parthenon frieze. However hard I stared at them, they refused to turn into anything resembling a photograph. In the ceramics department, the ceramics looked like jewellery. In the jewellery department, the jewellery looked like ceramics. Unless it featured bits of cast-off Chinese clothing, in which case it looked like fashion.

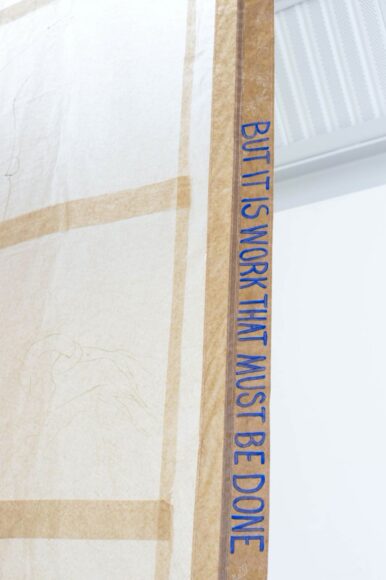

Some of the most compelling moments in the strong contribution by the painting department featured very little in the way of painting. I loved Kate Howe’s poetic deconstruction of the dark biblical story of Susannah and the Elders. It consisted of a giant paper banner with blue words arranged cryptically around its edges. In a tiny corner, a photograph of the artist’s ear, tattooed with a scorpion, referred to the Japanese actress Eiko Matsuda, the forgotten star of the controversial Japanese “pink” movie In the Realm of the Senses. So it’s a piece about cancelled women, a beautiful and inventive exhibit, with lots of feminine dismay, and the tiniest touches of painting.

While the upside of all this category jumping is a sense of widened horizons, the downside is an atmosphere of indiscipline: a feeling that hopping about is easier than staying put, and that artists today are happily licking all the ice creams in the shop.

It’s a suspicion that continues in the second of the tendencies discernible here: a taste for futurism and sci-fi. I lost count of the number of artists in every department who were imagining the next world along, a world of robotics and AI, of pulsing monitors and indistinct gender differences. On the CAP floor, Sara Sarshar gives us a piece called Youphoria where little green men play video games as they try to work out why aliens are alienated. Sometimes in sci-fi you sense a hope for the future. Not in Youphoria. All those endless months of Covid did tangible damage to the art student’s sense of optimism.

The third tendency is, predictably, an obsession with identity. Locked up in their bedsits, dodging the Miley Cyrus, the students of the RCA had little choice but to obsess about themselves. It’s particularly noticeable among the Far Eastern students who pack some of the floors here (80 per cent of the jewellery department consists of students from abroad). Cast adrift in a foreign land, ringed by Covid and alienation — it’s small wonder so many of the Chinese, Korean and Taiwanese artists who contribute so much to these shows fret so furiously about themselves, their grandmothers, their sexuality.

I wish I could blow a fairy dust on all of them that would make them stop looking down and start looking up.