The gods of art are at it again. Spreading disharmony and muddle. They have arranged for two ambitious shows about the black and African experience to open in the same week in London and for one of them to be joyous, uplifting and brilliant and the other neurotic, discomforting and dank. Those wicked gods of art certainly know how to confuse us.

Africa Fashion at the Victoria and Albert Museum looks at the sartorial history of the entire continent. We start in the independence era of the 1950s and 1960s, when African nations began breaking away from the colonial powers that controlled them, and continue to today, when a new generation of African designers is finding sparkling ways to mix the past with the present.

There’s a lot to like here. So let’s start with the clever pacing. Good curators know how to tickle the tummies of their audience. The first thing you see is a shimmering catwalk film in which stunning models in stunning pan-African showstoppers sashay past you in a stunning line. I could have stood there for ever, but there’s still a show to go, and having softened you up with the uncomplicated pleasures of the catwalk, the event gets suddenly gritty.

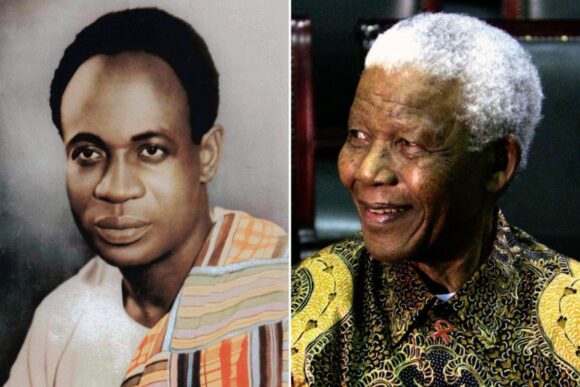

A series of documentary vitrines spell out how the independence movement in Africa used fashion to make its case. When Kwame Nkrumah led Ghana to independence in 1957 he made sure that in his state photographs he wore the bright and busy kente cloth, hand-woven and historically Ghanaian. It stood out from the surrounding suits like a light in the dark. Many independence days later, Nelson Mandela employed the same sartorial manoeuvre with his Madiba shirts.

The point being made is a deep one. In Africa, cloth and fashion have a special potency. As one of the wall texts puts it, quoting the sculptor El Anatsui, “Cloth is to the African what monuments are to westerners.” Something about the relationship between the body and what it wears is crucial to the African experience.

Having detoured into the documentary world to present this heavyweight opening idea, the show gets briskly down to the business of parading before us gorgeous garments draped on beautiful mannequins specially made for the event. (Standard mannequins come in a single shade of black and do not convey the diversity of African colours.)

Among the pioneering designers celebrated in these early stretches, two stood out for me. One was Alphadi, a Nigerien born in Timbuktu (known as the Magician of the Desert!), who adds strips of bright handwoven Tera-Tera cloth to traditional jackets and skirts, thereby shaking them awake. And the Malian Chris Seydou, who works with a local textile called bogolanfini, a cotton decorated with fermented mud.

The independence vitrines have already proved that this is a show that likes a detour. The next section is devoted to the studio photographers in Lagos and Accra who recorded the enthusiastic posing of passers-by.

The intention, I suppose, is to switch the focus from the clothes to the people, and the event does, indeed, get warm and fuzzy as it collects anonymous sitters. But powerful aesthetics keep punching through. What beautiful faces. What fabulous sartorial decisions. We are looking at a continent that is aesthetically blessed.

All this happens downstairs. Upstairs, the history lessons cease and the show gives itself over to spotlighting contemporary African fashion. It basically becomes a collection of wow moments.

Artsi Ifrach from Marrakesh gives us a contemporary take on the fully enveloping burqa with a golden toe-to-scalp number covered with talismanic hands to ward off the evil eye.

The South African Sindiso Khumalo appears to be remembering the Victorian look with a prim bonnet and matching dress, but when you examine the print from which they are made you see that it features Khumalo’s mother in traditional Zulu costume. The pact between the ancient and the modern is being repeated across the floor.

So that’s the uplifting show. The less pleasing and more neurotic one has arrived at the Hayward Gallery, where In the Black Fantastic collects work by black artists who use science fiction and myth as new pathways to examine black identity. Black issues are seen through the psychedelic lens of fantasy. When I walked into the first gallery, filled with the art of the American Nick Cave, I thought I was still at Africa Fashion. Cave makes “soundsuits”, human-sized wearable sculptures covered in sequins, buttons and flowers, which look like carnival costumes but apparently commemorate the deaths in police hands of a catalogue of black Americans.

Thus Soundsuit 9:29 is dedicated to the murdered American George Floyd. How the sculpture refers to the death remains unclear. Cave’s ornate and busy manner, with no detail left undecorated, turns out to be the show’s house style. Everything is done by accruing. Nothing by removal. Artist after artist adds and adds till the point they are trying to make becomes as difficult to discern as the hull of a boat encrusted with barnacles.

Only Kara Walker, who uses minimalist black puppets to act out a murderous passion play from the dark days of the American South, seems fully in control of her imagery.

The most disappointing exhibit is a lifesized Chris Ofili sculpture, Annunciation. It shows a black Angel Gabriel raping a golden Virgin Mary in a tangle of twisting limbs. You don’t need to be a fierce Catholic to find it graceless and sick. You just need to be a sentient human being.

Africa Fashion, V&A, London SW7, until Apr 16, 2023; In the Black Fantastic, Hayward Gallery, London SE1, until Sept 18