Few painters stand out from their times as fiercely as Edvard Munch. Born in Norway in 1863, he really was a one-off. His most famous painting, The Scream, with the howling munchkin clasping his hands to his head while the world swirls around him like the contents of a Kenwood mixer, was painted in 1893. It’s an astonishingly progressive image.

To pluck a comparison out of the air, 1893 was also the year in which, here in England, Edward Burne-Jones was still working on The Arming and Departure of the Knights of the Round Table on the Quest of the Holy Grail, with Guinevere and King Arthur on one side and Sir Galahad on the other. Munch’s art wasn’t just responding to another drumbeat. It was from another planet.

A gripping, whispery, haunting selection of his paintings has arrived at the Courtauld. It has been borrowed from the Kode Art Museum in Bergen, and brings 18 important pictures from Norway in a sudden and stirring cascade. His paintings are rare in Britain. The Tate owns one. And that’s it.

The show makes several things quickly obvious. The first is his technical progressiveness. Look closely into any picture here and you will see paint doing things that no one had ever previously asked of it. A throbbing stack of yellows — a traffic light with all its colours stuck on amber — describes the moonlight bouncing off some wet rocks on a beach. A couple of slashes, so quick they could win a fencing gold at the Olympics, evoke, perfectly, a pier jutting into the ocean. The shimmers and splodges around a woman’s head radiate out, out, out, like homemade radar markings that track her thoughts.

Just as tangible as the extraordinary inventiveness of his technique is the profound misery of his mindset. Munch’s art throbs with Scandi pessimism, especially on the subject of women. It even infects the rest of the Courtauld’s collection. I swear the Renoirs looked glummer when I came out than they had when I went in.

One good thing about seasonal affective disorder — he was surely a SAD sufferer — is that it makes you appreciate the sun more actively on the rare occasions that you encounter it. The earliest painting here, Morning, was painted in 1884, when Munch was just 20.

It shows a young woman staring out of the window as the sun pours in and bleaches her bedroom. One of her feet is bare. Her blouse is undone. So some taking off or putting on has been going on, and a sly sexual storyline is being sneaked into the picture, as often happens with Munch. But, overwhelmingly, Morning remains an emotional and eloquent tribute to the power of the sun.

From now on it’s Nordic noir all the way. In 1889 he paints his sister Inger on the beach. It’s a summer night by the fjord and the sun, in a final wave to the landscape, is doing spooky and silvery things with the reflections. Inger wears a white dress. This time the ecstatically glowing linen makes her look ghostly.

Summer Night, Inger on the Beach hovers beautifully between Munch’s first style and the wild and inventive ways ahead. By the next picture his paint has begun snaking around the shapes in that swirling, eerie, simplified style we know from The Scream. It’s a style that seems to elide the act of painting with the act of thinking. Munch doesn’t just paint scenes. He paints moods. Glum ones.

Evening on Karl Johan, from 1892, is a disquieting Oslo street view featuring a crowd of Scream-like skulls marching towards us like a parade of undertakers. A line of TS Eliot forced itself unbidden into my thoughts: “So many, I had not thought death had undone so many.”

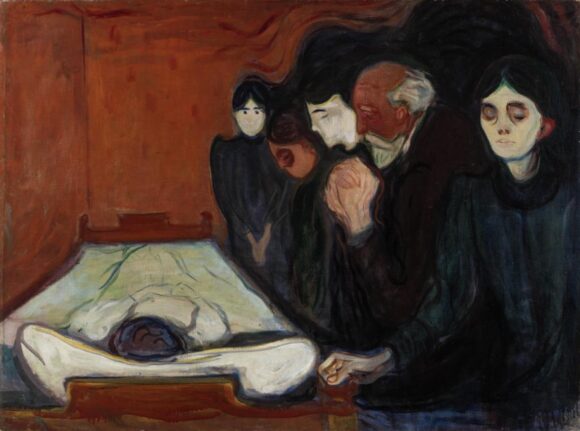

At the Death Bed, from 1895, shows the corpse of Munch’s elder sister Sophie, surrounded by the family. She had died of TB when he was 13. Yet he waited till he was 32 before he memorialised her passing in this grim farewell.

The art here never stops feeling intensely personal. And its me, me, me moods keep leading Munch to the subject of women. Unable in real life to maintain a balanced relationship with the ones who drifted in and out of his studio, he viewed them in his art with a tremulous mix of desire and terror.

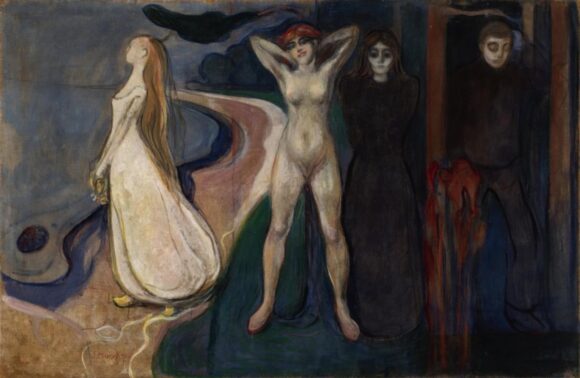

Woman in Three Stages, from 1894, is a particularly weird bit of Scandi symbolism in which a young girl in virginal white on the left becomes a mature nude in the middle and a white-faced widow in black on the right. Skulking in the shadows is a peeping man. I was admiring the stream of dark red paint descending from the central nude on technical grounds when I suddenly recognised it as a stream of blood. The first period blood in art?

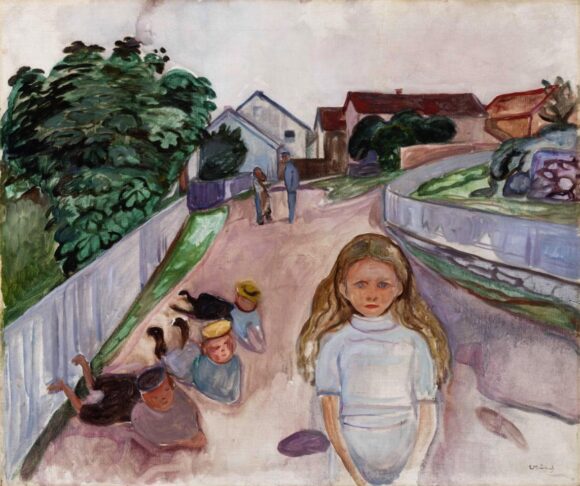

A pretty picture, from 1901, Children Playing in the Street in Asgardstrand, seems bright and optimistic, until you focus on the unsmiling little girl in the foreground — dressed again in symbolic Munch white — and notice how the little boys lying on the ground on the left seem to be ogling her. Is this really a picture about the battle of the sexes featuring a cast of ten-year-olds? I’m afraid it is.

Much of this angsty Nordic symbolism teeters on the edge of ridiculousness. It’s saved from modern disqualification by the spectacular inventiveness of the paintwork, and the sense you get in most pictures that Munch may be talking about himself, but he’s thinking about the rest of us. He’s not the only one who’s lost. We all are.

Edvard Munch: Masterpieces from Bergen is at the Courtauld Gallery, London WC2, until Sep 4