Some shows are so obviously a good idea you wonder why they don’t happen more often. So it is with From Near and Far, an exhibition devoted to collage at the Stephen Friedman Gallery.

The dictionary definition of collage — a piece of art made by sticking different materials such as paper, cloth or photographs on to a larger surface — doesn’t do the medium justice. In the right hands collage is a mirror with a truth filter, a way of rearranging reality so that important things become easier to see. Hannah Höch’s collages made evident the social harshness of Europe after the First World War. Richard Hamilton’s collages exposed the glamorous emptiness of 1950s consumer culture.

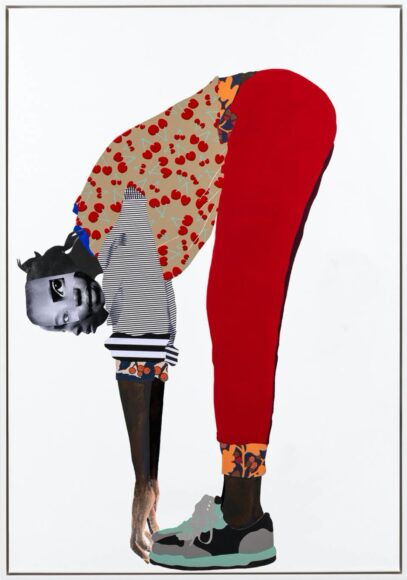

Not that the present show goes into any of that. It’s a celebration of contemporary collage, not a review of the medium’s heroic past. Sixteen female artists who use collage in punchy ways have been brought together by a pair of curators who themselves form an unlikely juxtaposition: the Texan artist Deborah Roberts, famed for her touching portrayals of black teenagers, and the British art historian Katy Hessel, queen of social media.

By focusing exclusively on female artists, Roberts and Hessel seem to be saying that collage is a medium that suits women. There’s certainly a domestic air to some of the images here. Chantal Joffe shows herself undressing. But because it’s a collage, assembled out of what look like bits of kitchen roll, the erotic is successfully transformed into the everyday.

Collage can also bring images together in juxtapositions that want to say big things about politics and society. In Hooded Captives, Martha Rosler combines two crouching figures, who look as if they are about to be beheaded by Islamic State, with a glamorous western model sashaying down a catwalk. It’s like watching the telly and seeing News at Ten followed by Love Island. The modern world has become another collage of jarring juxtapositions.

Mind you, not all the collages here look like collages. Expanding the definition of the medium to include works that involved the collage process somewhere along the way, Roberts and Hessel have managed to smuggle in some cracking paintings.

Amy Sherald’s A Golden Afternoon is a beautiful portrait of a man wearing three layers of coats — a yellow one, a blue one, a white one. Apparently Sherald tried out the colours in collage before painting them, which is how she arrived at this perfect decorative combination.

Kudzanai-Violet Hwami paints a tribute to lesbian love in which an image of a couple in bed crashes like a YouTube advertisement into a bigger image of a couple sitting on a sofa watching television. One painting, two sides of home life.

Collage can, therefore, turn artists into Time Lords and bring together different realities. It can juxtapose moods and sights, thereby reflecting the fractured nature of our times. And, yes, its scales and patterns do seem to suit women. But this isn’t a methodical show. Few of its conclusions are firmly reached. For me, the clearest truth being presented here is that women’s art, especially black women’s art, is on a roll. No arguments there.

One thing I expected to find more of in From Near and Far is surrealism. Not only is surrealism uber-trendy in feminine art circles, but the prophet of the movement, the Comte de Lautréamont, seemed also to be inventing collage when he described a young boy as being “as beautiful as the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table”.

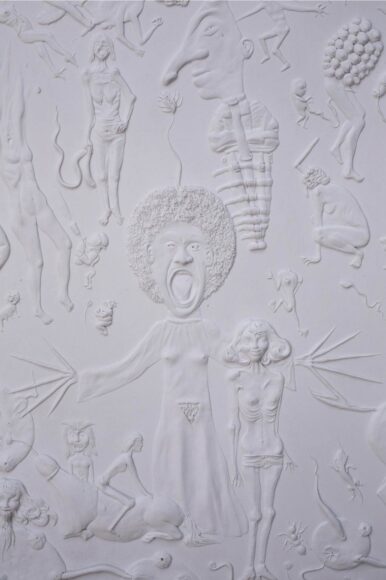

Fear not. The absence of surrealism in From Near and Far is more than made up for by the enormous, juicy, monstrous, slithery amounts of it to be found in Tim Noble’s extraordinary new show at Darren Flook. Noble used to be part of another celebrated double act in contemporary art, Noble & Webster, masters of miraculous shadows. They split up a few years ago and disappeared. Until now.

It turns out that Noble has been making spectacularly weird relief sculptures out of jesmonite, a handy mix of gypsum and resin that dries to something that looks much like plaster. Out of this adaptable material he has fashioned bizarre and busy little worlds in which anything can and does happen. Imagine —and this will require an effort — a cross between Hieronymus Bosch and the Parthenon frieze. That’s what we have here.

Foetuses do the hokey cokey. Dogs turn into pigs. Blobs become munchkins. Penises grow on trees. And all the time the whole writhing lot of them seem to be scurrying about the jesmonite like angry ants whose nest has been prodded. It’s bonkers. And rather brilliant.

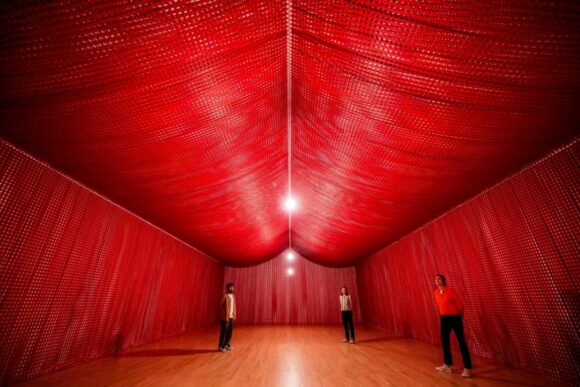

So too is half of the Cornelia Parker retrospective at Tate Britain. It’s the first half, where her most famous installations are gathered: the garden shed blown up with Semtex; the pieces of silver flattened by a steam roller. Where so much conceptual art puts everything into the thought and nothing into the visuals, Parker’s contributions to the genre are genuinely exciting to look at.

Where the show goes wrong is in her films. Oh dear. They are so worthy and ponderous. It’s like when a great singles band decide to make a concept album. In an effort to be deep, everything slows down and expands till it isn’t worth the bother.

From Near and Far, Stephen Friedman Gallery, London W1, until Jul 23; Tim Noble, Darren Flook, London E2, until Jul 16; Cornelia Parker, Tate Britain, London SW1, until Oct 16