Art history is an indisciplined discipline. Invented by German scholars of the 18th century, it was an attempt to force the rules of science on to the wild and unrulable territory of art. This belongs here, that belongs there, the Germanic mind insisted as it sought to turn a blancmange into cubes. But in its hunger to describe, date and classify it got so much wrong.

Take Carlo Crivelli (c 1430-c 1495). Where does he fit? Nowhere, really. A near contemporary of Botticelli, he was born in Venice but spent most of his career in the Marche, that especially indistinct stretch of Italy that has Rimini to the north and Pescara to the south.

Datewise he ought to have been a classic Renaissance artist, but Crivelli’s output was too gothic to pass for a rebirth and too naturalistic to be properly gothic. He’s so difficult to place that the pseudo-science of art history has generally chosen not to bother, and he has been ignored.

Fortunately the director of the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, Jonathan Watkins, is a fan. Ever since he wrote an enthusiastic student’s paean to Crivelli in 1988 he has nursed an ambition to mount a show about him. Now, finally, it has happened. I should quickly add that the Ikon is a contemporary art gallery, so the act of putting on Crivelli here is in itself anomalous and even a bit mad.

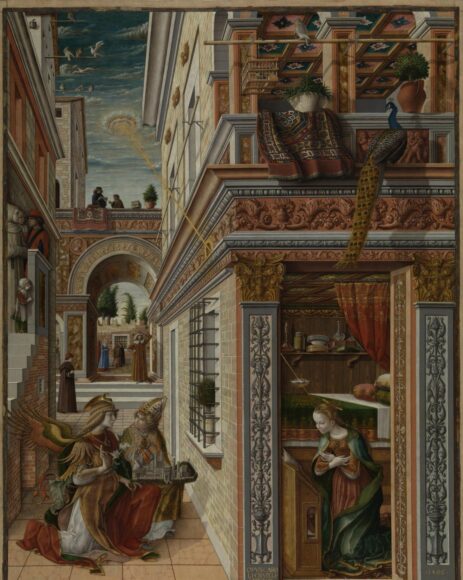

The event’s most obvious ambition is to highlight Crivelli’s illusionism: the dazzling moments of trompe l’oeil that make you look twice at his art to see if something is real or not. Like the fly that seems to have buzzed in and settled on a parapet in front of the Virgin Mary. Or the exquisite fruit and vegetables that hang above her head.

What’s puzzling about these beautifully achieved illusions is that they actively contradict the stylised presence of the saints themselves. No one could ever accuse a Crivelli Madonna of being realistic. The particularly beautiful one lent by the Vatican wears an outfit so ornate it would win the show-stopper category on Bake Off. She is transparently a creature of the heavens, delicately and precisely outlined in an unreal manner that stresses her divinity.

Yet this same Crivelli, in the same picture, paints a peach hanging from a branch in Jesus’s hand that is so evidently juicy you can feel yourself biting it. Another Crivelli trick is to have his holy folk step over the edges of their niches so that their feet poke convincingly into our space. It’s repeated by every saint in the show — the suffering St Roch, showing you his plague sores; St Catherine the martyr, with the spiked wheel that mutilated her; Mary Magdalene with her pot of prostitute’s perfume. All of them push a toe into our world. Why?

The catalogue and Watkins’s 1988 essay are keen to view this impactful illusionism from a contemporary angle: as a conceptual game. Watkins even manages to quote the poststructuralist philosopher Jean Baudrillard in his appreciation, which must be a world first. But to impose contemporaneity on Crivelli you need to ignore his powerful religiosity. And that is the impossible bit. Everything here has such a fierce religious glow to it.

The Vatican’s gorgeous Madonna oozes saintly tristesse as she cuddles the baby Jesus on her knee and ponders his upcoming death. Look, too, at the intense piety displayed by the mini monk at her feet: he’s no larger than a squirrel, but his religious passion is elephant-sized.

The National Gallery, the show’s most generous lender, has sent a couple of crackers to argue Crivelli’s case. You won’t find a more convincing cucumber in art than the one poking over the edge of the parapet in the famous Annunciation, with St Emidius.

In The Vision of the Blessed Gabriele we see a Franciscan monk from Ancona kneeling before a miraculous vision of the Virgin Mary that has appeared in the sky. His belief is so strong you can feel it on the other side of the room. But just as tangible are the trees that surround him, his church, his sandals, his Bible.

Why are these two realities colliding? What’s going on? The simple answer, I suggest, is that one style describes God’s world and the other describes ours. The fly, with its implications of rotting and death, doesn’t belong in heaven with the saints. It’s a trespasser from our own guilty kitchen. The apples hanging above the Madonna’s head may look solid enough to bite, but they are also reminders of the fruit that we ate in Paradise when God specifically told us not to. Crivelli’s art is determined to remind us not only of our original sin, but of the dimension in which it occurred. Our dimension.

Appended to the show is a provocative interjection by the illusionistic sculptor Susan Collis. Her contribution looks like some humble rubbish left behind by the installers. Rawlplugs in the wall. A dirty broom for sweeping up. An overall covered with stains. Only when you peer closely do you discover that the Rawlplugs are made of precious jasper and the screws from 18-carat gold; that the white and red stains on the broom are actually mother of pearl matched with loosely shaped rubies.

Collis’s art is playing games with our perception, and doing it cleverly in a thoroughly contemporary fashion. But she has no higher purpose than to amuse and to puzzle. And that’s the difference between now and then.

Carlo Crivelli: Shadows on the Sky is at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham until May 29