Volume IV of John Richardson’s magnificent, unparalleled biography of Picasso is about half the length of the preceding volumes. And as we have been waiting for it for an eternity — 15 years to be exact: the last volume came out in 2007 — there may be a temptation to view it as an anticlimax, or even a let-down.

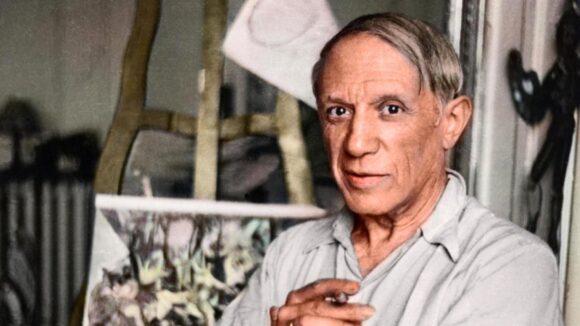

Its timescale — it covers the years 1933-1943 — takes us deep into Picasso’s career, but leaves us well short of an ending. Picasso died in 1973. There are still 30 fruitful years of his art to go. Richardson himself, meanwhile, departed in 2019, at the impressive age of 95, turning this ambitious project into an amputee.

It is also true that art history itself has been going through convulsions since the publication of Volume I in 1991. The rise of feminist art history has changed the climate drastically for Picasso. An artist once viewed almost universally as a genius is now viewed almost universally as the embodiment of art’s misogynistic past. Volume IV has arrived in exceptionally inauspicious circumstances. How it manages to be as gripping as it is, as fresh as it is, only the gods of art can answer.

The years under consideration are some of the most tumultuous in Picasso’s long and twisty life. Dark things were happening to him on many fronts. Domestically he was trying to extricate himself from an ugly marriage to the Russian ballerina Olga Khokhlova. Olga imagined she had married a glamorous art star with whom she could enjoy a fashionable and frilly Parisian life. Instead she had wound up with an egotistical schemer who put his art first in any situation and was busily expressing his scorn for her in his work.

A particularly distressing story told by Richardson sees Picasso taking Olga to the theatre to hear Pagliacci: a surprise visit to her world. When they return home he undresses her affectionately and they make love. The next morning the bell rings. A visitor has arrived at the door. He has come to serve Olga with divorce papers. Picasso, meanwhile, strolls around the apartment singing Pagliacci “at the top of his voice”.

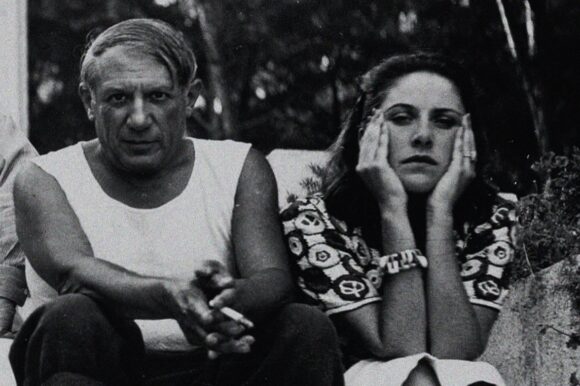

Volume I of A Life of Picasso began with the observation that every time the maestro swapped mistresses he changed styles. It was an opinion Richardson inherited from Dora Maar, the surrealist photographer whose presence comes to dominate the present tome. Meanwhile he is also regularly visiting Marie-Thérèse Walter, the beautiful young blonde whose voluptuous presence dominated the previous instalment.

Maar was the lunar opposite of Walter: brunette, intelligent, demanding, neurotic. Her pitiful letters to Picasso, full of apologies and broken outpourings of love, make for uncomfortable reading. His treatment of her, running in parallel to his treatment of Olga, is unforgivably callous.

However, as Richardson convincingly opines, the great paradox of Picasso’s entire career, and especially of the years under consideration here, is that his art “tended to thrive on the dark side”. Turmoil and shadows triggered his best work. Thus the tragic Maar is the inspiration for seemingly countless variations on the theme of the Weeping Woman: where her feminine tears stand in for a darkening world.

Richardson is typically sniffy about the most famous of these lachrymose portrayals, the great painting in Tate Modern — “whose popularity with the general public has much to do with its readability” — but, as always in all these volumes, a forensic examination of Picasso’s oeuvre builds successfully into a vivid account of his life.

The habitual cruelty of the self-styled minotaur of art to his women has already been documented. What gives the current volume a different kind of drama is the sudden arrival on its pages of a new personage: Picasso the political artist. Having spent his career until now firmly avoiding political issues, he is transformed by events in civil war Spain. And particularly by his hatred of Franco.

The painting of Guernica, a process recorded in detail in Maar’s photographs, and accompanied here by one of Richardson’s trademark psycho-aesthetic deliberations on the exact meaning of the great masterpiece — he does like his Freud — feels also like an address to the contemporary world.

It was Goering who organised the brutal annihilation of the Basque town of Guernica as a belated birthday present to Hitler. Richardson remembers as a schoolboy seeing Picasso’s antiwar masterpiece at the Whitechapel Gallery, where it had been sent on an awareness-raising tour of Britain. It’s the kind of aside that makes this biography matchless. On matters Picasso Richardson is both an intimate witness and a ravenous historian.

Subsequent chapters deal with the occupation of Paris by the Nazis and Picasso’s extraordinary decision to stay in the city and face them. As his next mistress, Françoise Gilot, would later remember, he was “impervious to fear”. The same outrageous egotism that made his artistic journey so selfish enabled him to confront the Nazis, while painting and sculpting some of his most memorable accusations.

Where the French artists fled to New York or decamped to Nice, Picasso stayed. His towering belief in his own importance, which in other situations comes across as a blackness of character, turns into something heroic and cheerable in the occupied Paris of the Second World War.

Unfortunately, no sooner have we felt the contemporary resonance of these grim wartime chronicles than we reach 1943: the terminus of the tome. When he started Richardson was going to write Picasso’s entire life in four volumes. The last one was going to take the Master of Malaga to the end. But the previous instalments silted up with so much detail that the completion of the task became impossible.

What now? No one will ever again be able to combine Richardson’s personal familiarity with Picasso with such impressive levels of history, insight, detail, gossip and breezy writing. The greatest art biography ever written can never have a proper ending. It’s an incomplete masterpiece. But a masterpiece nevertheless.

A Life of Picasso Volume IV: The Minotaur Years: 1933-1943 by John Richardson