Self-portraiture goes down well with an art audience. I certainly have a special place for it in my heart. Its secret, I think, is that it intensifies your relationship with the artist and makes it feel personal. It’s an illusion, of course, but a pleasing one.

Small wonder, then, that Vincent van Gogh became a premier league self-portraitist alongside Rembrandt, Goya and Gauguin. Having led a life that even by troubled-artist standards was problematic and brief, it was a nailed-on certainty that he would spend some of it staring into a mirror and “baring his soul”.

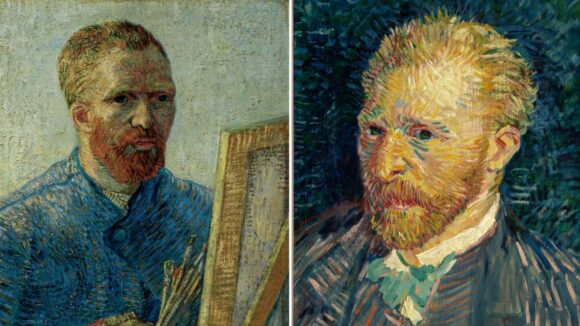

Somewhat perversely, however, the fascinating survey that has arrived at the Courtauld Gallery — it includes almost half of the 37 self-portraits he painted — appears determined to calm our image of him. The Van Gogh presented to us here is less victim, more investigator; less crazy, more thoughtful; less of an isolated genius, more of an artist of his times. That the Courtauld is seeking to work this trick with self-portraits — the most obviously personal of art’s genres — isn’t just counter-intuitive, it’s downright brave.

Van Gogh didn’t take up self-portraiture until he arrived in Paris in 1886, barely four years before he died aged 37. There are no juvenile starings into the mirror of the sort we might have expected from an artist of his timbre and no early displays of angst. Once in Paris, though, he threw himself in front of the mirror and refused to budge. Two thirds of all his self-portraits date from the era, half from a single year — 1887.

The first time we see him he’s sitting in the dark wearing a heavy black homburg, staring at us with grim solemnity. He had been living louchely in Montmartre for a few months, but is still trying to pass himself off as respectable bourgeois. The bleak atmosphere he has given himself would also fit an undertaker.

In truth, the Paris he had arrived in was a city bursting with progressiveness. The impressionists were completing their sequence of revolutionary exhibitions. Pointillism was being launched. So was symbolism. Everything was in flux. And, hey presto, it all started to affect Van Gogh with remarkable fierceness.

Taken one at a time, the many Paris self-portraits are not especially impressive. They come in a single format — head and shoulders, 14in x 12in, face in the middle, plain background — and there’s little deviation in them from the standard Van Gogh look: serious, staring, bearded. Put them all together, however, and you have an action movie.

In just 12 months, in an extraordinary display of artistic transformation, a dull brown caterpillar turned into a brightly coloured butterfly. The Vincent we see at the end of the process — straw hat perched jauntily on his head; funky blue smock instead of grim black suit; sunny dashes of colour emanating from his face like water from a sprinkler — isn’t just a different artist. He’s a whole new being.

Watching this progress through a dozen intermediate paintings, each of which sees him taking a small step forwards, is like running your thumb through a flick book. So furious is the rate of change from Johnny Come Lately to Leader of the Pack that some of the joys we usually search for in self-portraiture go missing.

There is, for instance, not much sense here of that intense and intimate relationship between you and the artist that artistic selfies usually prompt. Nor is there much investigation of changing moods or varied expressions. And given how many likenesses there are of Vincent, it’s strange how little convincing evidence they provide of how he actually looked. The staring eyes, the hollow cheeks, the bright red beard are repeated so regularly they have a cartoonish sense of encapsulation about them.

The one new thing I did learn about his appearance is that he had a big nose, with a hook to it. You notice it in a self-portrait drawing, and keep seeing it everywhere after that.

While the Paris year is examined in spectacular depth, his next journey to Arles, where he cut off his ear, and the sojourn in the mental hospital in St Rémy, where he went to recover his sanity, are only sketched in thinly. Given how important the Arles period was in his story — it is where he produced many of his best-known works — it’s curious how little self-portraiture was involved.

The present show confines the evidence to just one painting — the Courtauld’s own Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear. A couple of others are missing, notably his finest, the one where he casts himself as a shaven-headed Japanese monk. Harvard wouldn’t lend it.

The Arles self-portrait, a covert Crucifixion in which the tortured Van Gogh equates his fate with that of Christ on the cross, is the first picture we see here with clear ambitions to say something dramatic and intimate about himself. In all the preceding art he uses himself as a cheap and convenient model on whom to practise fresh styles and techniques. Here, though, he wants us to know him through his art.

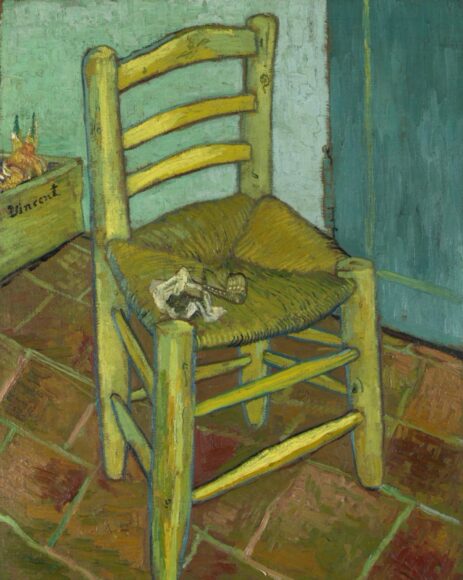

It’s a symbolic approach that the show backs up by also including the famous painting of his chair, in which the chair clearly stands in for him.

The two St Rémy portraits that complete the journey have a before and after feel about them. In the first he strikes a confident artistic pose: palette in hand, white shirt, clipped beard. In the second the black dog has ravaged him and he stares out at us resentfully, like a sullen child who has been scolded.

It’s the very end of the how. But only now does he give us something that might pass for a peep into his soul.

Van Gogh Self-Portraits, at the Courtauld Gallery, London WC2, until May 8

Van Gogh in the UK

Before Van Gogh became a painter he spent four years from 1873 until 1877 living on and off in the UK, and it shaped his life. At 20 he took a job in London, working for an art dealer.

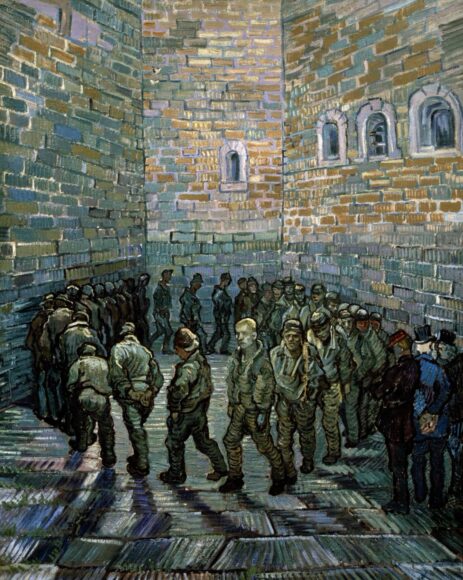

He walked all over the city, including from his lodgings in Stockwell to Covent Garden, rowed on the Thames and spent hours at the National Gallery studying Turner and Constable. Ideas of social reform were circulating and he read JS Mill’s On Liberty. His subsequent painting Prisoners Exercising (1890) was inspired by a trip to Newgate Prison.

But his personal life was in tatters. He fell in love with his landlady’s daughter. When it wasn’t reciprocated (she was already engaged to a former lodger) he fled to Paris.

In 1876 he returned to teach at a boys’ school in Ramsgate, where he felt happy and peaceful. When the school moved to Isleworth, he joined them, but eventually became absorbed elsewhere, working as a Methodist preacher.

It was this that took him back to Amsterdam to study theology, but he always remembered the Kent sea air fondly. There are blue plaques for him in Ramsgate and at 87 Hackford Road, where he lived in Stockwell. This house is now a museum, hosting artist residencies, exhibitions and events.

Susannah Butter

How to drink Absinthe — the Van Gogh way

Watch Waldemar Januszczak drink the ‘green fairy’ in the style of ‘Henry’ Toulouse-Lautrec and Vincent van Gogh